Team:Duke/Modeling/3

From 2013.igem.org

Contents |

Mathematical Modeling of Bistable Toggle Switch

Kinetic Model of Bistable System

Following Gardner's Work...

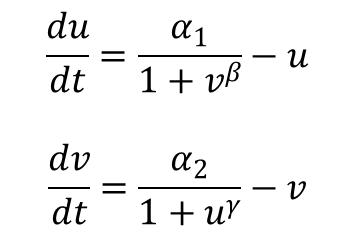

Tim Gardner from Jim Collins' Lab of Boston Univeristy published one of the first major papers on genetic toggle switch. In his work, he used a kinetic approach to model the stability of a genetic toggle switch. His equations involved two equations expressing the change in the level of two mutually repressive repressors with respect to time.

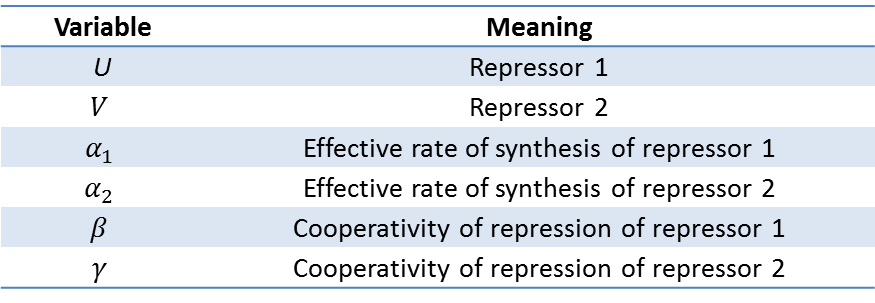

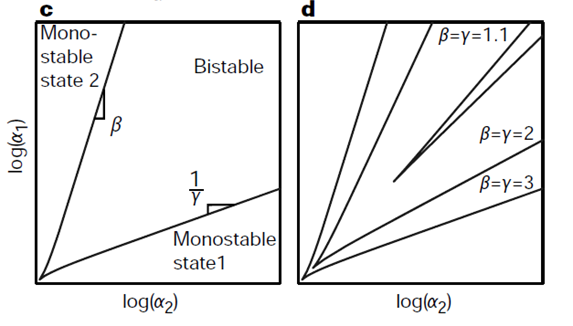

Using this model, Gardner produced the two graphs shown below. The first is a graph of nullclines. Nullcline, also called zero-growth isocline, is a line that represents the set of points at which the rate of change is zero. In this example, the two nullclines shown are where rate of change of repressor 1 (U) and repressor 2 (V) are zero. It is clear that at the intersection of these two nullclines are steady-state points of the system because these are points where the change of both repressor levels with respect to time is zero.

The difference between the two figures with nullclines on left and right is that the system on the left is bistable with the system on the right is mono-stable. Figure (a) shows that there are two stable steady-states where only one of the two repressors exists at a high level, inhibiting the production of the other repressor. There exists a third intersection in the middle, however, this point can be mathematically shown to be unstable using the eigenvalue of the Jacobian matrix involving U and V (workings not included here). The value of U and V doesnt change exactly at this unstable steady-state, however, the level of repressors will quickly diverge from this point even at the smallest perturbation. The figure on the right, figure (b), shows that at a different combination of parameters, a system can be mono-stable where the nullclines only intersect once at a stable steady-state solution.

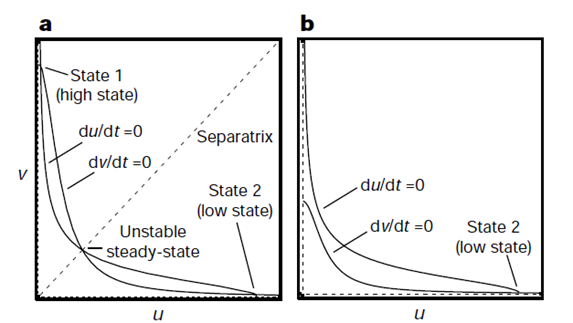

Another set of graphs from Gardner's work is shown below. The two plots are bifurcation diagrams of a system, again, with two mutually repressive genes. Bifurcation is a mathematical term that describes a phenomena "when a small smooth change made to the parameter values (the bifurcation parameters) of a system causes a sudden 'qualitative' or topological change in its behavior" (Blanchard). In terms of this system in question, bifurcation occurs when the system changes its stability (Change between monostability and bistability).

The graphs below shows the effect of change in cooperativity on the bifurcation region. On the two axes are rate of synthesis of the two repressors, which can be translated as the strengths of the two promoters. According to the graphs, the bifurcation increases as cooperativity increases. In other words, increasing cooperativity of mutual repression allows a set of two weaker promoters to have bistability.

Following his work, I have generated plots that show nullclines of two repressors for various combinations of the parameters alpha1, alpha2, beta, and gamma (which is equivalent to a1, a2, n1, n2 in the plots below). In addition to the nullclines, the plots show the trajectories of how points with different initial conditions on the level of U and V end up at either of the two stable steady states. All the trajectories are color-coded in terms of where they eventually end up--the line across the middle labeled as "separatrix" separates the initial conditions that lead to one solution from the initial conditions that lead to the other solution. Two interesting observations can be made. First, some trajectories reach close to the unstable-steady state but when it gets very close to it, it quickly diverges to either of the two stable steady-state solutions. Secondly, the plot on the right shows that when the set of promoters are chosen appropriately, the system becomes monostable and all initial points end up at the single stable steady-state solution.

Development of Our Kinetic Model

With the understanding of bifurcation regions and their meaning on a system of two mutually repressive genes, we have created our own kinetic model with the purpose of exploring the conditions necessary for a system to be bistable.

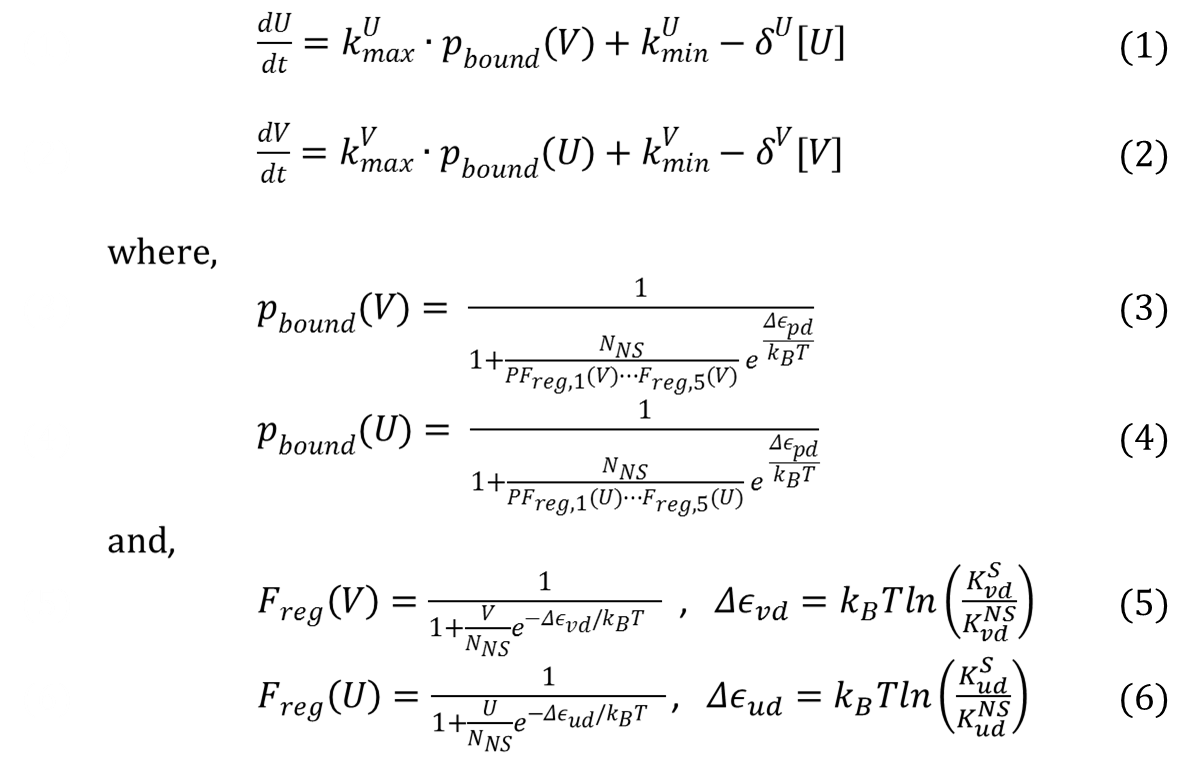

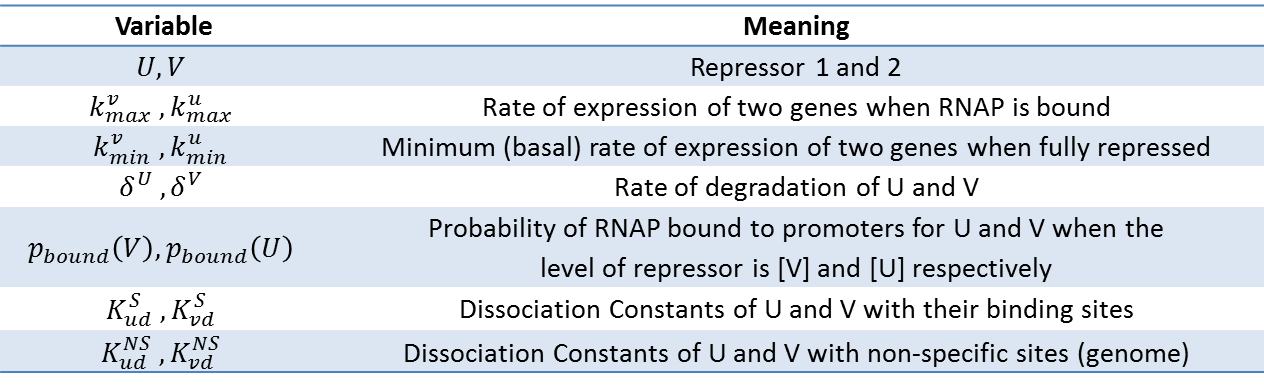

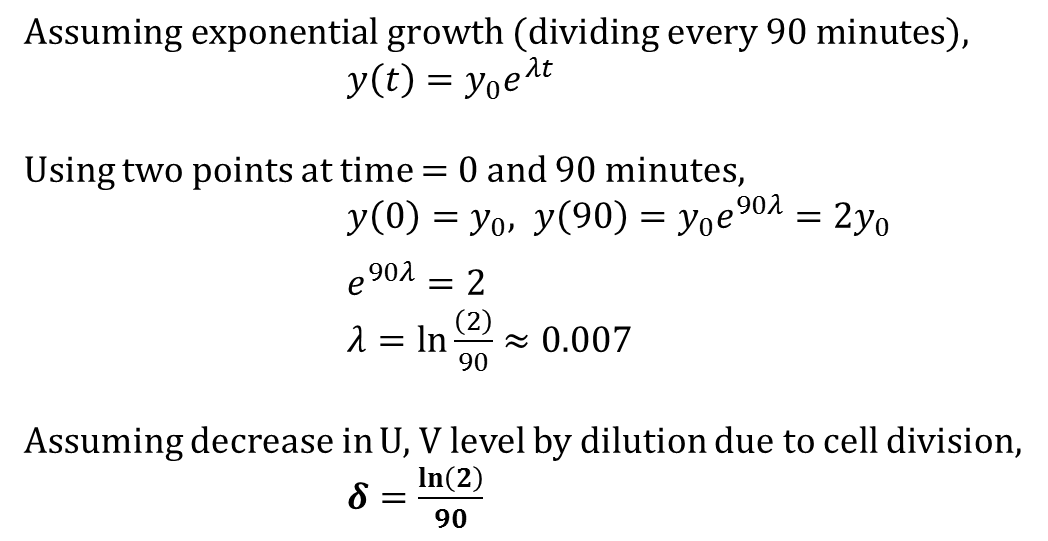

Our model shown below incorporates the Pbound term from our thermodynamic model. In this sense, this model is a combination of kinetic and thermodynamic model. As mentioned before, a key assumption in this model is that the gene expression is directly proportional to the probability of RNAP bound to the promoter. Also, same values for used for variables that appeared in the thermodynamic model (i.e. P, Nns, Kb, T,...). If we assume that our repressors are never actively degraded, the only way to decrease its concentration is by dilution due to cell growth. This assumption links the degradation rate (more precisely, dilution rate) (delta) to the growth rate of the yeast. Further, if we also assume exponential growth, ln(2)/90 is the growth rate of S.cerevisiae dividing every 90 minutes. As such, ln(2)/90 was used as the value of delta throughout the model.

Our kinetic model assumes five repressor binding sites and that there exist a basal level of gene expression even at maximum repression (phenomenon which we will call "leakiness" of the promoter). Where as Gardner's model used promoter strengths and cooperativity of repression as parameters to control the bifurcation regions, this model includes a lot more parameters: for example, promoter strength, leakiness of promoter, strength of repressor binding, and number of binding sites. Also, our model uses the probabilistic Pbound term which models what actually happens during gene expression: physical binding of RNAP to the promoter. In this sense, our model is more comprehensive and more mechanistic and the previously suggested model by Gardner.

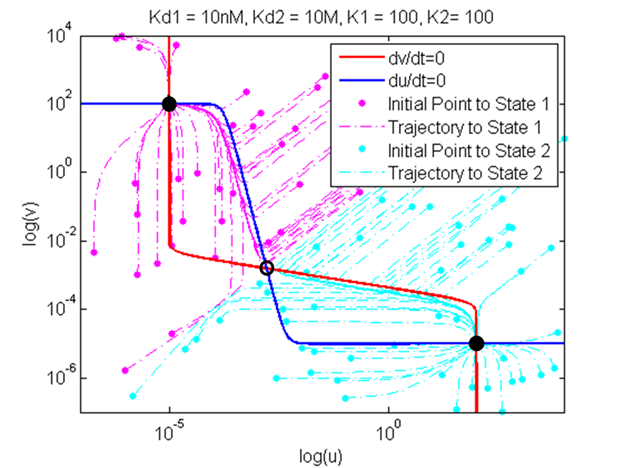

A plot of nullclines and trajectories was produced using our kinetic model. The plot above shows that our model can demonstrate a bistable system when given appropriate parameters. In the subsequent section, our kinetic model will be applied to the system to test the effect of various parameters on the bifurcation regions.

Results from Our Kinetic Model

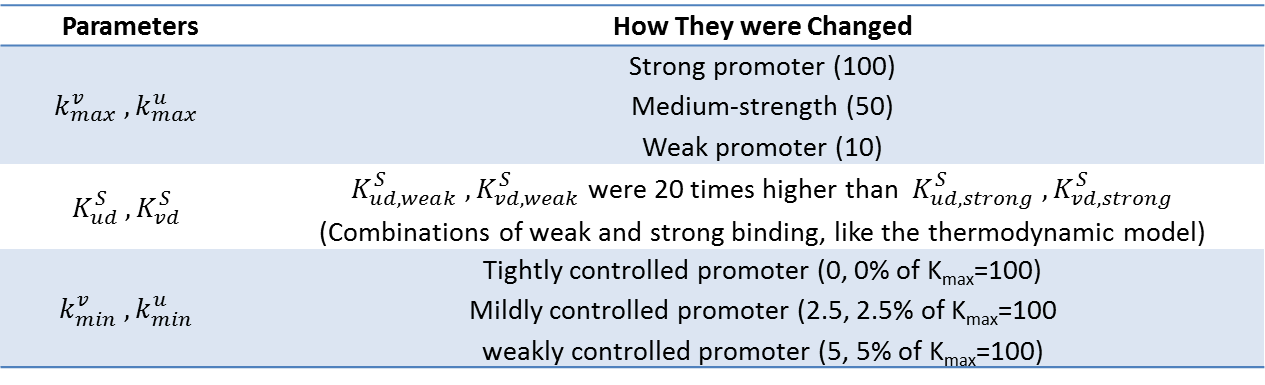

Our model was used to demonstrate the effect of changing various parameters on bifurcation regions of the system. Specifically, the strength of promoters, combination of strong and weak binding repressors, and basal rate of gene expression (leakiness of promoters) were changed. The parameters changed, their values, and their meanings are tabulated below. Bifurcation regions for the different parameters were plotted and are also shown below. Note that the axes of the plots are not promoter strengths but binding strengths of the two repressors. Using these values on the axes, we could see how the constraints on the strength of repressor binding to achieve bistability changed.

This plot shows that the bifurcation region shrinks when the strength of one promoter is decreased. When a promoter is weak, the repressor binding strength must be high to achieve a bistable system. This result can be explained by the fact that weaker promoter leads to lower level of repressors, and that stronger binding strength is required to achieve the same level of repression with a lower repressor level.

In this plot, a combination of weak and strong binding were used to demonstrate the effect of unbalanced binding strengths on the bifurcation region. As the number of weak binding increased, the bifurcation region shrunk diagonally. This result is intuitive in that increasing the number of weaker binding requires stronger repressors to achieve the same level of repression and thus maintain bistability.

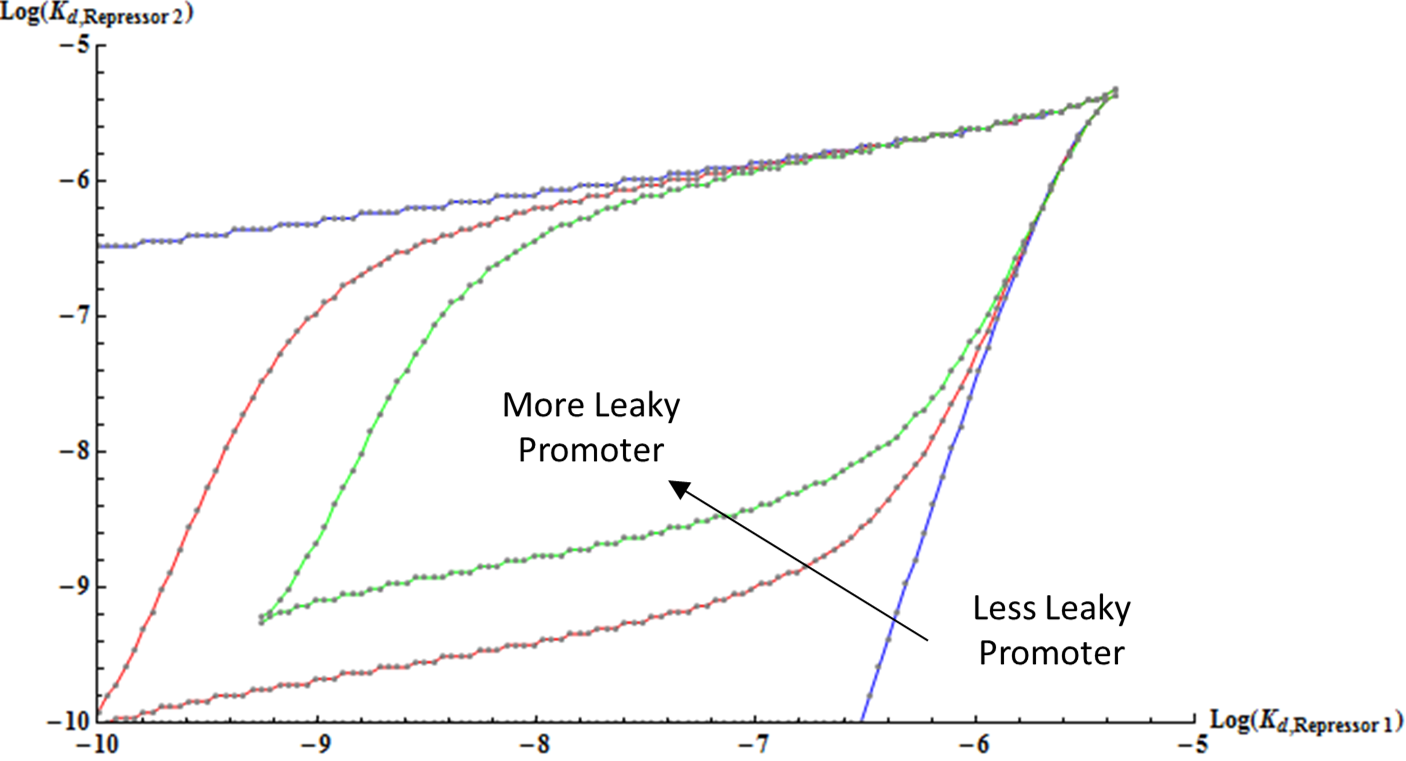

Finally, the effect of increasing the leakiness of a promoter is shown here. Interestingly, as a promoter becomes more leaky, the boundary of the bifurcation region curves inwards and forms an enclosed shape. This result is reasonable because when a repressor is extremely strong, even low basal level of expression can have strong repression of the other gene, thus leading to monostability.

Therefore, we have demonstrated the effect of various parameters on the bifurcation regions for a set of two mutually repressive genes. Our results show how the bifurcation decreases with decreasing promoter strength, weaker binding, and leakier promoter; these results consequently suggest the range of possible values for the dissociation constants of the two repressors that can lead to bistability. From the results of both thermodynamic model and the kinetic model, we now have a theoretical guide to constructing a genetic toggle switch; a guide that can be used to couple two genes that have the optimal combination of cooperativity, number of binding sites, binding strengths, promoter strengths and leakiness.

Mathematica Code

The Mathematica codes used for the thermodynamic model can be found here.

References

- Gardener, T. et al. Construction of a genetic toggle switch in Escherichia coli. Nature. 403, 339-342 (2000).

- Blanchard, P.; Devaney, R. L.; Hall, G. R. (2006). Differential Equations. London: Thompson. pp. 96–111.

"

"