Team:Bielefeld-Germany/Project/MFC Efficiency

From 2013.igem.org

MFC Efficiency

In order to get a better evaluation of our Microbial Fuel Cell, we calculated several characteristic numbers. Furthermore, we searched and found a feasibility study and compared it with our results.

Verification, comparison and appraisal of measurement results

After consultation with expert Dr. Falk Harnisch and the productive feedback of our presentation and poster session during the European Jamboree in Lyon the need for verifying our measurement system and a technical and economic appraisal of the results became very obvious.

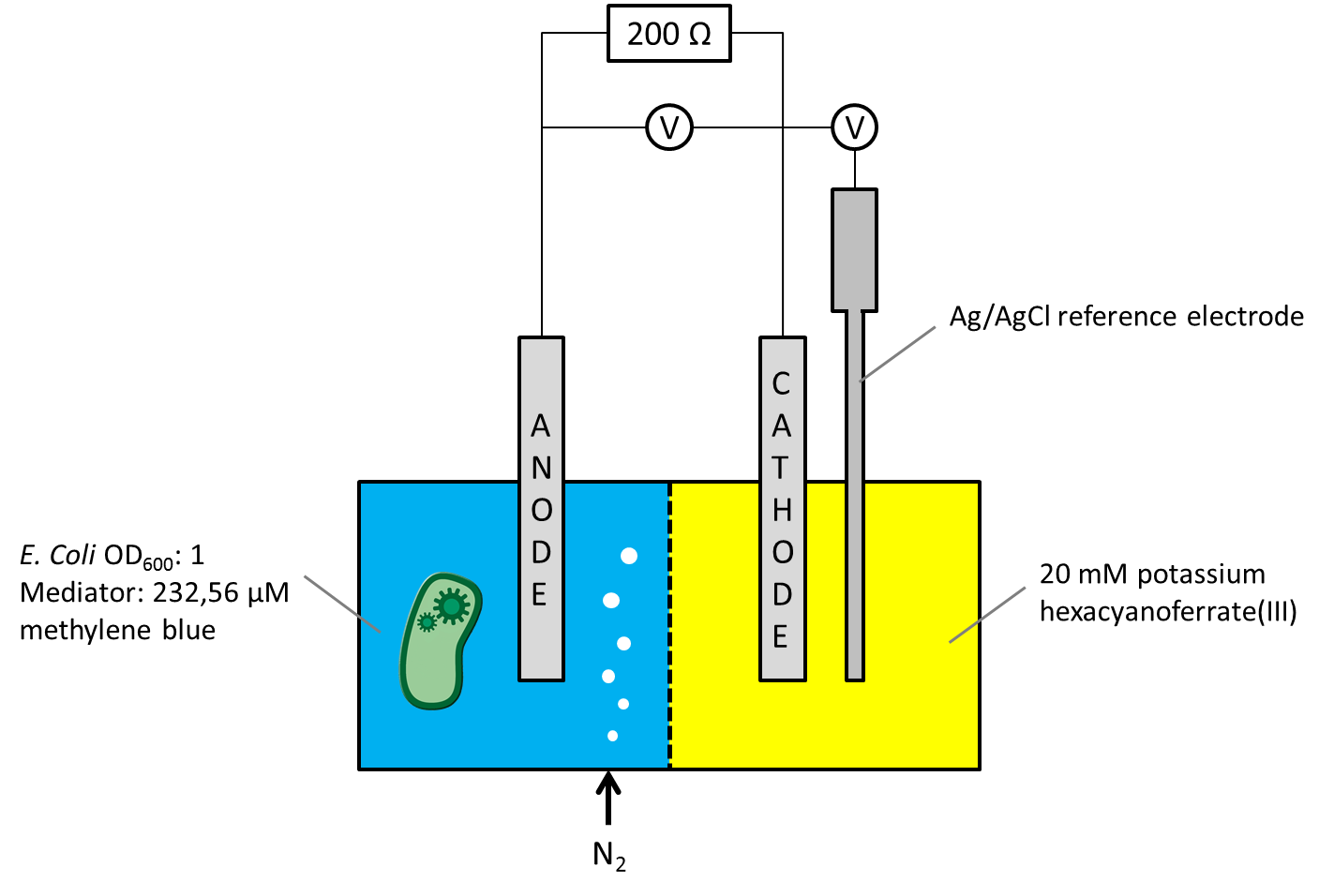

As the overall cell-voltage represents the difference between anode and cathode potential, it was not clear whether the measured voltage values were influenced by the biocatalytic activity in the anode chamber only, or by a combination of potential changes in both chambers. For independent consideration of the anode or cathode compartments potential, a Ag/AgCl [http://www.meinsberger-elektroden.de/labor/bezug.html#se10 reference electrode] was ordered and the Gen3plus MFC was designed and constructed to make the new electrode usable. The circuit diagram, including a schematic illustration of the entire measurement setup is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Schematic illustration of the Gen3plus MFC measurement setup, using a Ag/AgCl reference electrode.

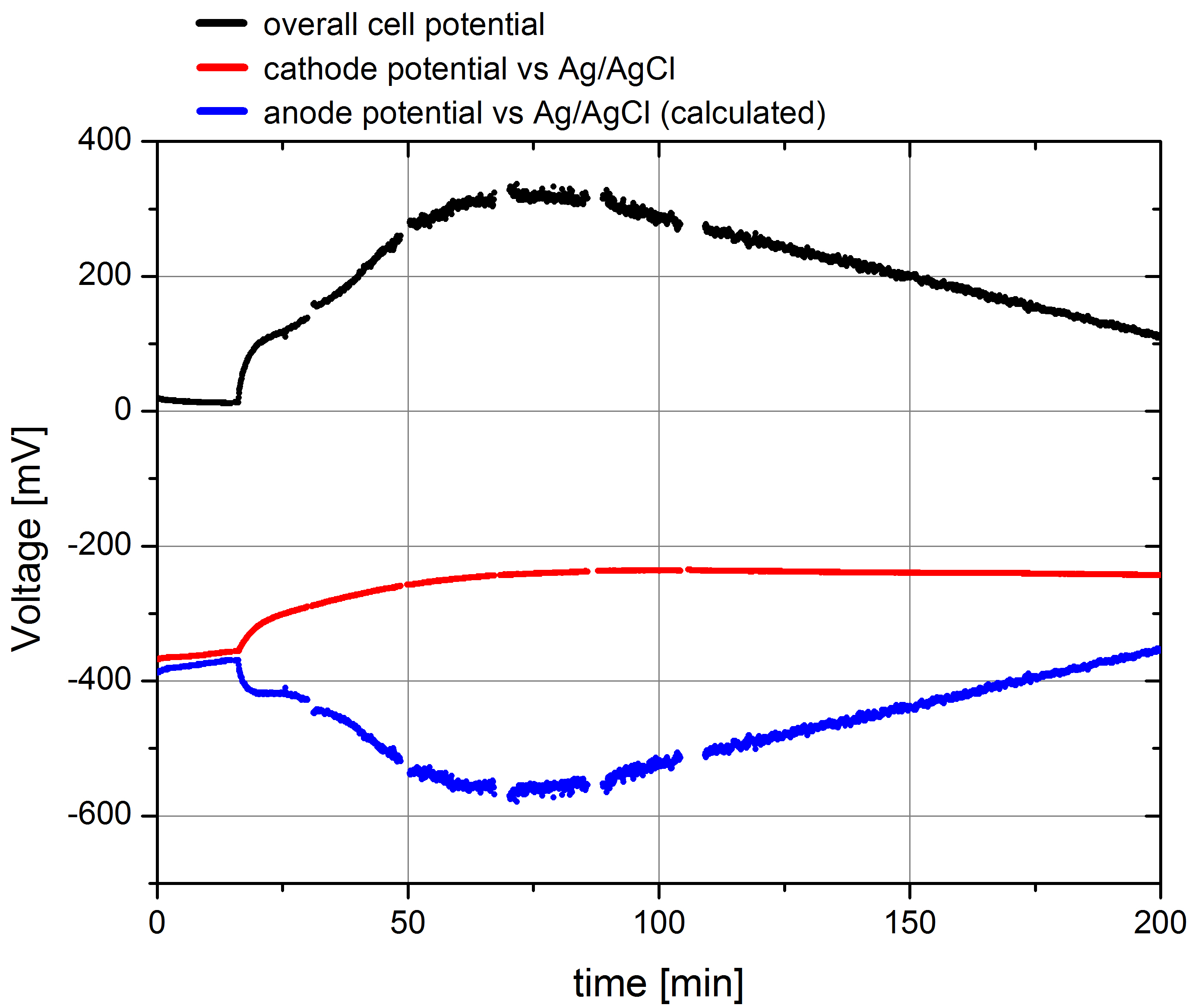

- Using this setup the parallel measurement of both the overall cell potential and the potential of the cathode were measured. The according data, including the c anode potential, calculated from Pcell= Pcathode - Panode are plotted in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Plot of the overall cell potential, cathode potential against Ag/AgCl reference electrode and the calculated data for the anode potential for a measurement of wild type E. coli KRX, OD 600 : 1,66 in the Gen3plus MFC. Methylene blue was added after 15 minutes with an end concentration of 232,56 µM.

The depicted data show the expected results. In the beginning the cell potential is very low, because the cells cannot transport the produced electrons to the anode. After addition of the mediator solution the cell potential shows a characteristic increase and reaches its maximum of 325 mV. The cathode potential against Ag/AgCl amounts about –360 mV at the start of the measurement, what was expected by calculating the potential using Nernst equation. The course of the measured potential values also shows a significant effect of mediator addition because of a polarization of both electrodes regarded to the resulting current flow, but it reach a stable value of -240 mV quickly. This and the calculated anode potential data show, that the anode potential is mainly responsible for the overall cell potential, so that the measurement of this value is suitable for the analysis of different bacteria strains or even enzymes, placed in the anode chamber.

As the detailed description of the Gen3plus MFC indicates, the cell is furthermore optimized for a better power output in terms of a larger volume, higher N2 aeration and an adapted mediator concentration. To generate different operating numbers for the established microbial fuel cell generation three plus the determination of the used substrate amounts was necessary. Because of the incompatibility between the mediator methylene blue and the separation column used for sugar analysis, a new purification method was established. The methylene blue containing samples were blended with a spatula tip of activated carbon to bind the mediator, inverted for two minutes and centrifuged at 10000 x g for 5 minutes. To exclude an effect on the substrate concentration standard samples, containing different amounts of mediator and activated carbon, were analyzed using the substrate HPLC method. As the results showed no differences for methylene blue containing standard samples treated with activated carbon and the untreated sample, the applicability of the method could be verified.

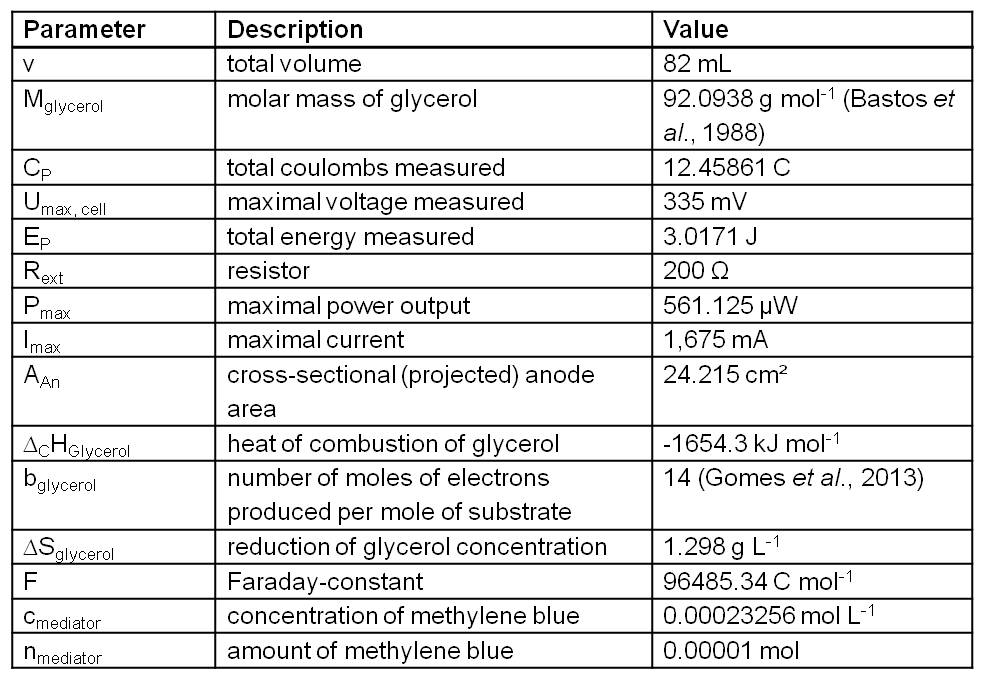

The relevant data for calculating the subsequent operation numbers based on the experiment presented in Figure 2 are presented in Table 1.

Table 1: Measurement values recorded and calculated from the experiment presented in Figure 2 and further data needed for operation number calculation. (Bastos et al., 1988 and Gomes et al., 2013).

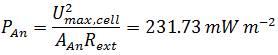

To compare the power output of the Gen3plus MFC, containing E. coli KRX (OD600=1.66) in M9 medium and using 232.56 µM methylene blue as mediator with other Microbial Fuel Cell systems the power density is normalized to technical characteristics (Logan et al., 2006). Because the anode is the part of the Fuel Cell where the biocatalytical reaction occurs, its projected surface area is an often used parameter for normalization:

To compare the system related to economic considerations like reactor size and material costs the power output is also normalized to the total volume of the Fuel Cell:

In comparison to measurements by Liu et al., performed in a single-chamber Microbial Fuel Cell the calculated values are in the same dimension. In their measurement the power generated with acetate as substrate was 506 mW m-2 or 12.7 mW L-1 and 305 mW m-2 or 7.6 mW L-1 using butyrate (Liu et al., 2005). Although the values reached with the Gen3plus MFC are little lower, they can be described as positive results since Liu et al. used domestic wastewater to inoculate their cell with a mixed culture of bacteria which are naturally adapted to anaerobic respiration (Liu et al., 2005). Since the results of the genetic optimized E. coli strains illustrate the potential of genetic optimization in regard to a higher power output, a further increase in power output using E. coli can be assumed upon further research.

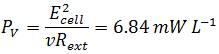

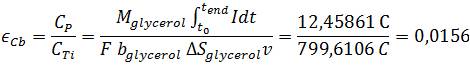

Further important operation numbers to characterize the efficiency of a Microbial Fuel Cell are the maximum possible electric charge and the theoretical amount of energy. The so called Coulombic efficiency describes the ratio of electric charge which is actually transferred from substrate to the anode to the theoretical maximum of produced Coulombs. Based upon the following reaction, the maximum number of electrons produced per substrate is 14 (Gomes et al., 2013).

The total electric charge was determined by integration of current, calculated from voltage using Ohms law over time:

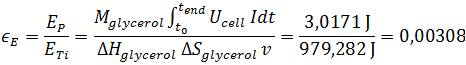

For calculating the energy efficiency, defined as the ratio of power production to the heat of combustion of the organic substrate, the power production was integrated over time:

The calculated values of 1.56 % for the Coulombic efficiency and 0.308 % energy efficiency are located at the lower end of the available literature values (Liu et al., 2005; Logan et al., 2006). The exact cause cannot be determined accurately because of the multitude of factors affecting the power output in a Microbial Fuel Cell. Relevant reasons might be the high energy amount of glycerol in contrast to wastewater, the Microbial Fuel Cell setup which is optimized for measurement value generation, or the organism E. coli. As stated previously E. coli is not adapted for anaerobic respiration and because of this fact a long term power output which is necessary for a high efficiency has not been possible right now and further genetic optimization is needed.

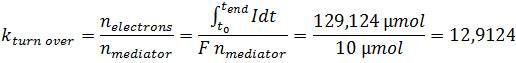

Since the mediator is an important factor, in regard to its essential function as the electron shuttle between E. coli and the anode, the mediator functionality was characterized. For that purpose the mediator turnover number was calculated which is defined as the ratio between the amount of transported electrons and the amount of mediator:

The obtained turn over number of about 13 illustrates, that methylene blue is used as a reversible redox mediator. During the 200-minute experiment each mediator molecule transports on average 13 electrons from the bacterium to the anode. As this value corresponds to a turnover of 0.065 min-1 the mediator activity of methylene blue could be a limiting factor in regard to the low efficiencies, too. To elucidate this hypothesis, a further investigation of the redox system is necessary, because the corresponding potential differences are essential for the efficient transfer of electrons between the substances used.

All in all the calculation of different operation numbers illustrate the general functionality of the Gen3plus MFC. The comparison with literature data for related systems is problematically because mixed cultures are used in most cases, but first achievements highlight the potentials using methods of synthetic biology to optimize the biocatalytic process.

Feasibility study for MFC in sewage and waste treatment

To assess the usability of our MFC regarding potential applications, we searched for a feasibility study and compared it to our results. It shows, that our currently achieved efficiencies have the potential for efficient energy production in real world applications.

The study

Feasibility study for the application of a Microbial Fuel Cell in sewage and waste treatment ([http://www.dbu.de/projekt_26580/_db_1036.html AZ 26580-31])

Funded by the ‘Deutschen Bundesstiftung Umwelt – Osnabrück‘

Reporting period: 16.12.2008 – 31.08.2010

Author:

- Prof. Dr.-Ing. Michael Sievers1

- Dr. Ottmar Schläfer1

- Dipl.-Ing. Hinnerk Bormann1

- Dipl.-Ing. Michael Niedermeiser1

- Prof. Dr. Detlef Bahnemann2

- Dr. Ralf Dillert2

- 1 Clausthaler Umwelttechnik-Institut GmbH – CUTEC-Institut GmbH

- 2 Leibniz Universität Hannover

Summary

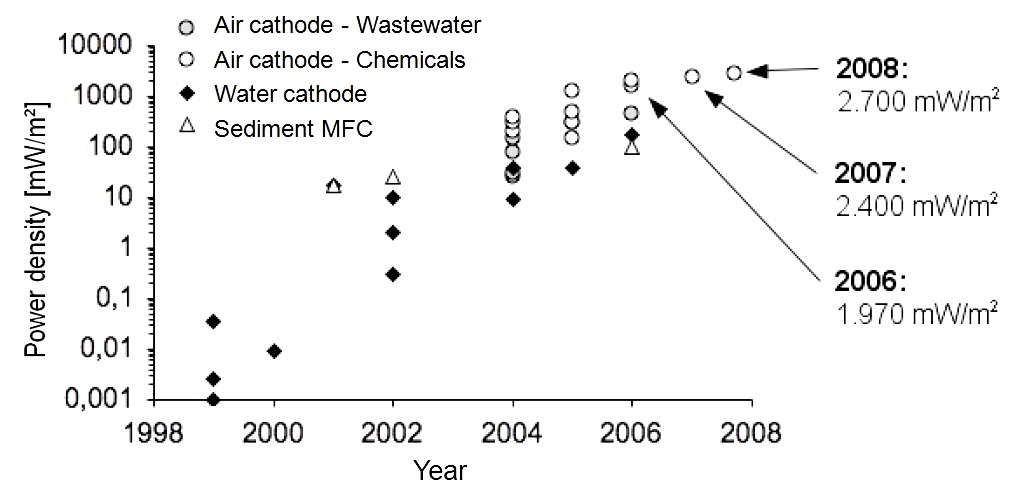

Since the first investigations on mediatorless MFCs in 1999, the maximum power densities increased from 0.05 mW/m2 in 1999 to 2700 mW/m2 in 2008. Therefore, this feasibility study refers to a power density of 2 W/m2.

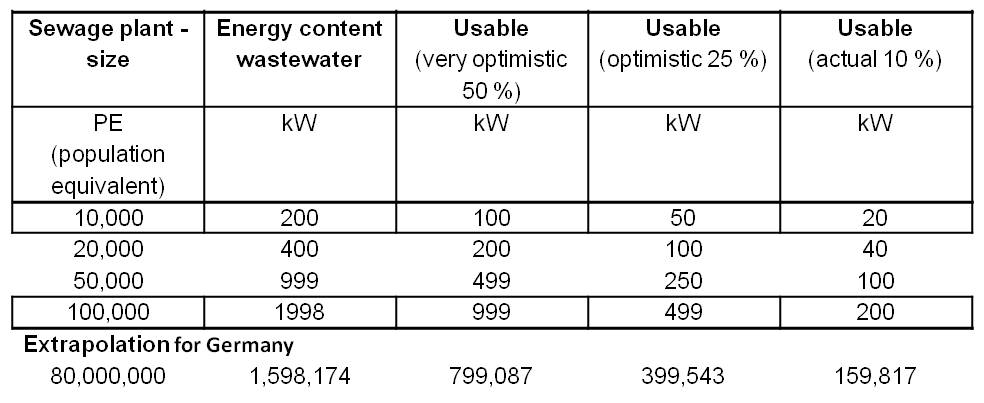

An estimation of the power generation potential shows, that the usage of an MFC could produce around 20 kW for a 10,000 PE (population equivalent) sewage treatment plant. The integration of an MFC would generate an electricity production and saving potential, which provides the opportunity to enable nearly energy self-sufficient sewage treatment plants. This is based on a low cost production with low cost materials of the MFC. Especially electrode and membrane materials have to be cost-saving.

Previous development of the maximal achieved power densities with MFCs

Since the first investigations on mediatorless MFCs in 1999, the maximum power densities increased. Figure 3 (Logan, 2008) shows the development of the power density from 0.05 mW/m2 in 1999 to 2700 mW/m2 in 2008.

Pure chemicals (glucose or glycerol) are much better usable than organic wastewater components. Furthermore, the conductivity of the organic liquid is usually much higher. Consequently, power densities achieved with wastewater tests are lower. On closer examination of the cathode, we can observe a higher power density for air cathodes (wastewater treatment) in comparison to water cathodes (degradation of pure chemicals). Air cathodes are additionally fumigated.

Assessment of the potential for applications

The energy content of waste water is about 20 W per population equivalent (PE). Therefore, a 10,000 PE plant could generate a power of 200 kW. Table 2 shows an overview of the electricity production potential for various wastewater treatment plant sizes with an extrapolation for 80 million people (Number of inhabitants of Germany). The energy content of the water is defined by the COD (Chemical oxygen demand). COD is commonly used to indirectly measure the amount of organic compounds in water.

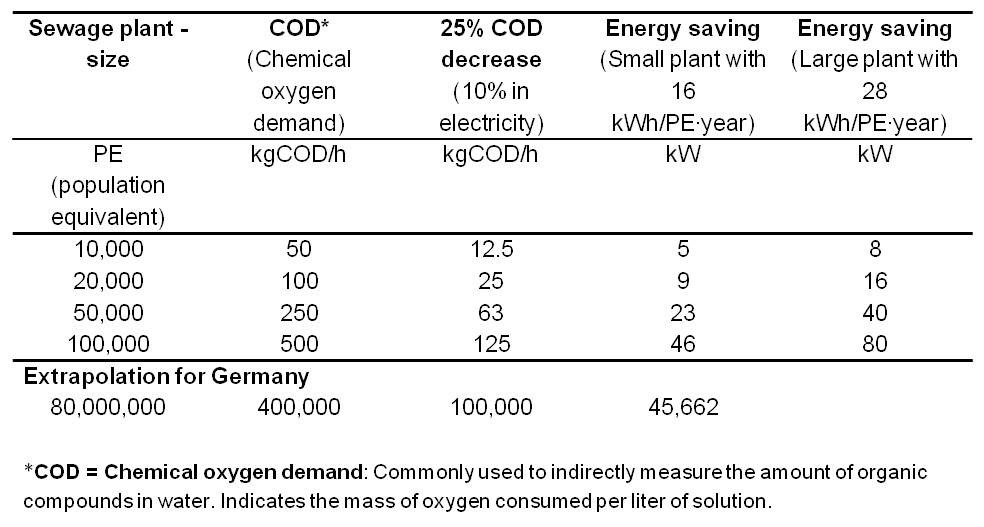

Table 3 summarizes the electricity savings potential for various wastewater treatment plant sizes with an extrapolation for 80 million people (number of inhabitants of Germany).

In comparison, a fully optimized plant for 100,000 inhabitants has an average power consumption of 285 kW. The integration of an MFC would generate an electricity production potential and electricity savings potential of up to total 246 kW. Thus, the Microbial Fuel Cell provides the opportunity to enable energy self-sufficient sewage treatment plants.

Assessment of our Microbial Fuel Cell

With our self-designed and constructed Microbial Fuel Cell we achieved a power density of 231 mW/m2. (Calculation of the power density). In contrast to the assumed power density for the feasibility study, which was 2000 mW/m2, we have still a ten times lower power density. That means the total electricity saving potential would be 25 kW, which shows a reduction for the required energy of 8% for a fully optimized sewage plant for 100,000 inhabitants with an average power consumption of 285 kW.

In conclusion, while our MFC has quite some potential for improvements, even now our system might be usable to realize significant energy savings.

References

Bastos M, Nilsson SO, Ribeiro da Silva MD, Ribeiro da Silva MA, Wadsö I (1988) Thermodynamic properties of glycerol enthalpies of combustion and vaporization and the heat capacity at 298.15 K. Enthalpies of solution in water at 288.15, 298.15, and 308.15 K. The Journal of Chemical Thermodynamics 20(11): 1353-1359.

Gomes JF, Gasparotto LH, Tremiliosi-Filho G (2013) Glycerol electro-oxidation over glassy-carbon-supported Au nanoparticles: direct influence of the carbon support on the electrode catalytic activity. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys.

Liu H, Cheng S, Logan BE (2005) Production of electricity from acetate or butyrate using a single-chamber microbial fuel cell. Environmental science & technology 39(2): 658-662.

Logan BE, Hameler B, Rozendal R, Schröder U, Keller J, Freguia S, ... & Rabaey K (2006) Microbial fuel cells: methodology and technology. Environmental science & technology 40(17): 5181-5192.

Logan BE (2008): Microbial Fuel Cells. John Wiley & Sons Inc., New Jersey.

"

"