Team:Edinburgh/Introduction

From 2013.igem.org

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

<div class='content'> | <div class='content'> | ||

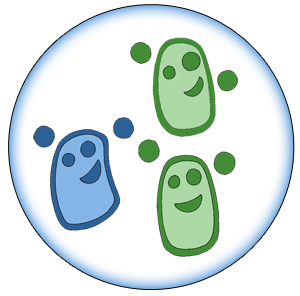

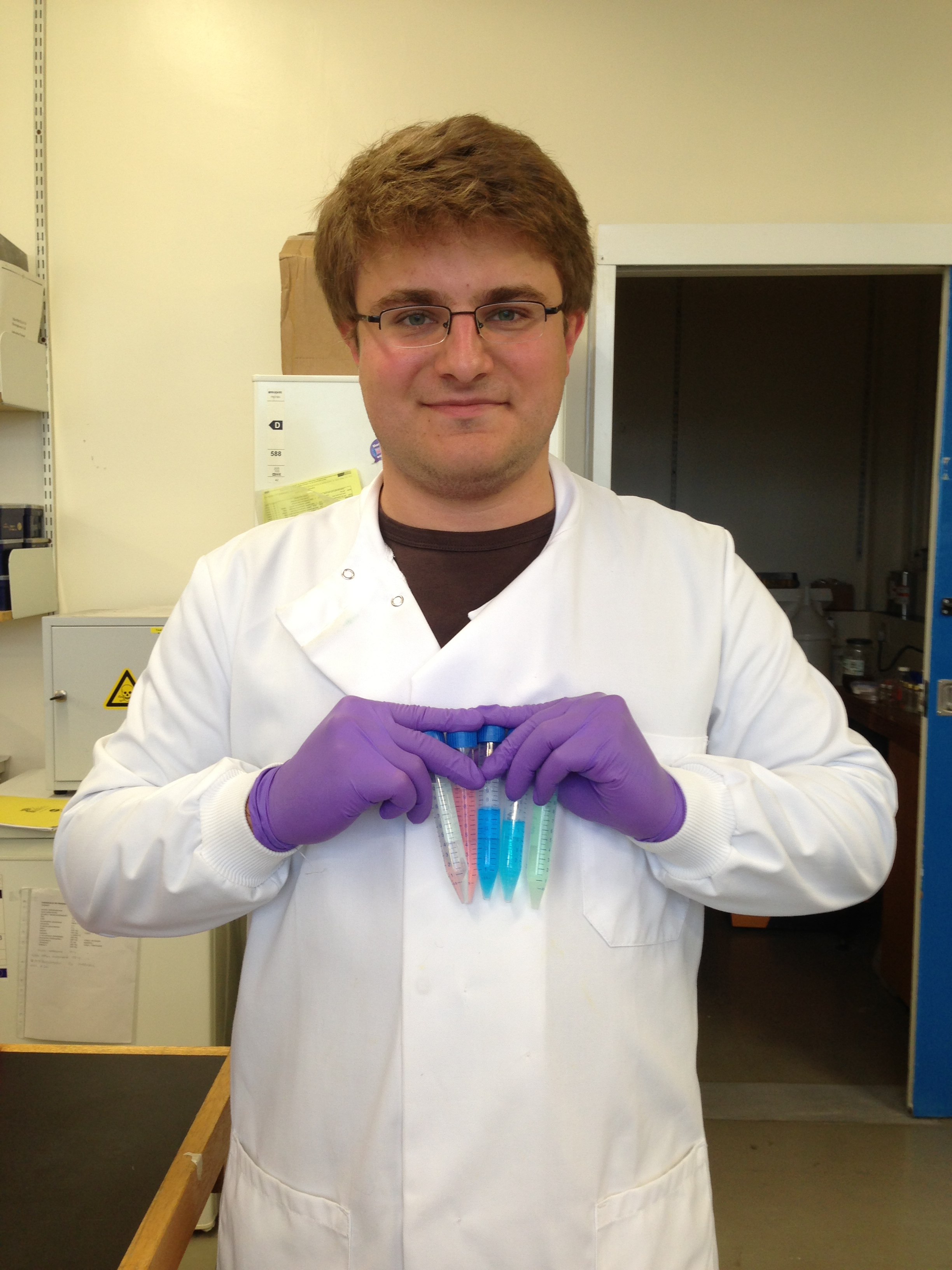

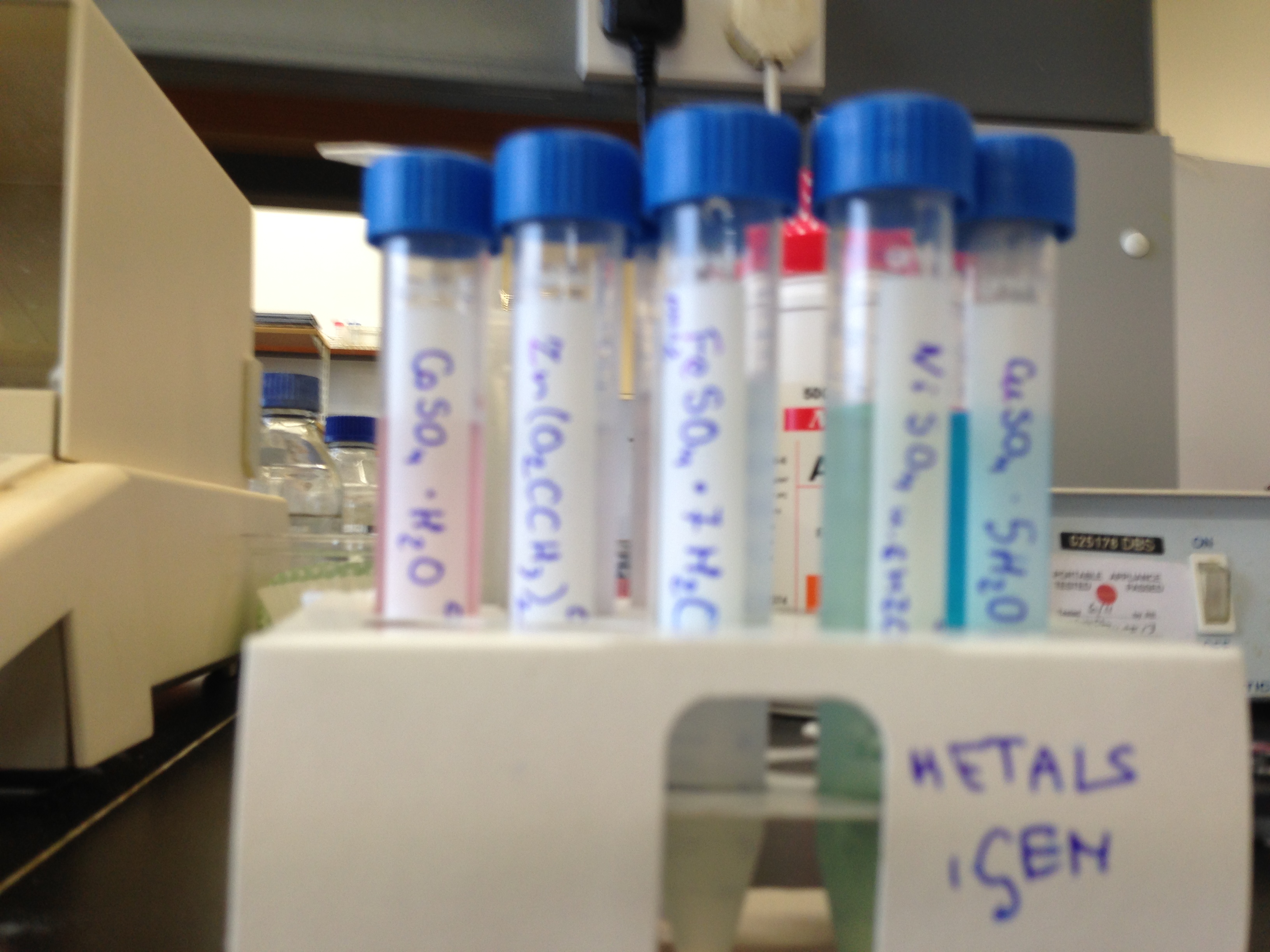

| - | Our aim was to create a self-contained system for bioremediation and valorisation of toxic waste waters produced by the key [ | + | Our aim was to create a self-contained system for bioremediation and valorisation of toxic waste waters produced by the key [[Team:Edinburgh/Human Practices/Industries Scottish industries]]. We have identified two major components of the industrial waste streams, which are believed to have the most detrimental effects on the environment: heavy metals and fermentable organic compounds. Heavy metals can be dangerous to both health and the environment and, unlike other pollutants, they do not decay. They can lay dormant and have the potential for bioaccumulation and biomagnification. This leads to heavier exposure for some organisms, such as coastal fish and seabirds, than is present in the environment alone. Fermentable organic waste on the other hand is deleterious in a less direct way. When released to the water bodies, it can lead to occurrence of harmful algal blooms, which are of increasing concern in Scotland and worldwide through their negative effects on the biodiversity, human health and economy. |

We have decided to use <i>Bacillus subtilis</i> as our chassis and the first step in our project was to characterise it (hyperlink to chassis characterisation) by looking at its responses to varying ethanol and heavy metal concentrations. We then went on to create a sensory system for metal detection (hyperlink to metal promoters), followed by metal binding (hyperlink to metal binding). We have decided to convert the fermentable organic compounds into ethanol (hyperlink to ethanol production intro), which can have many potential application. As co-localisation has been previously shown to speed up metabolic pathways (see team Slovenia 2010[https://2010.igem.org/Team:Slovenia Team Slovenia 2013]), we wanted to exploit this principle to increase ethanol production in bacteria by production of fusion proteins (hyperlink to alcohol production results). To achieve this we have employed and tested a new assembly method, called GenBrick (hyperlink to GenBrick). Finally, we wanted to see how our manipulations might affect cell metabolism, by combining a modular model of the whole cell (hyperlink to modelling), to which different pathways can be slotted in. | We have decided to use <i>Bacillus subtilis</i> as our chassis and the first step in our project was to characterise it (hyperlink to chassis characterisation) by looking at its responses to varying ethanol and heavy metal concentrations. We then went on to create a sensory system for metal detection (hyperlink to metal promoters), followed by metal binding (hyperlink to metal binding). We have decided to convert the fermentable organic compounds into ethanol (hyperlink to ethanol production intro), which can have many potential application. As co-localisation has been previously shown to speed up metabolic pathways (see team Slovenia 2010[https://2010.igem.org/Team:Slovenia Team Slovenia 2013]), we wanted to exploit this principle to increase ethanol production in bacteria by production of fusion proteins (hyperlink to alcohol production results). To achieve this we have employed and tested a new assembly method, called GenBrick (hyperlink to GenBrick). Finally, we wanted to see how our manipulations might affect cell metabolism, by combining a modular model of the whole cell (hyperlink to modelling), to which different pathways can be slotted in. | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

{{Team:Edinburgh/Footer}} | {{Team:Edinburgh/Footer}} | ||

Revision as of 16:10, 4 October 2013

Our aim was to create a self-contained system for bioremediation and valorisation of toxic waste waters produced by the key Team:Edinburgh/Human Practices/Industries Scottish industries. We have identified two major components of the industrial waste streams, which are believed to have the most detrimental effects on the environment: heavy metals and fermentable organic compounds. Heavy metals can be dangerous to both health and the environment and, unlike other pollutants, they do not decay. They can lay dormant and have the potential for bioaccumulation and biomagnification. This leads to heavier exposure for some organisms, such as coastal fish and seabirds, than is present in the environment alone. Fermentable organic waste on the other hand is deleterious in a less direct way. When released to the water bodies, it can lead to occurrence of harmful algal blooms, which are of increasing concern in Scotland and worldwide through their negative effects on the biodiversity, human health and economy. We have decided to use Bacillus subtilis as our chassis and the first step in our project was to characterise it (hyperlink to chassis characterisation) by looking at its responses to varying ethanol and heavy metal concentrations. We then went on to create a sensory system for metal detection (hyperlink to metal promoters), followed by metal binding (hyperlink to metal binding). We have decided to convert the fermentable organic compounds into ethanol (hyperlink to ethanol production intro), which can have many potential application. As co-localisation has been previously shown to speed up metabolic pathways (see team Slovenia 2010Team Slovenia 2013), we wanted to exploit this principle to increase ethanol production in bacteria by production of fusion proteins (hyperlink to alcohol production results). To achieve this we have employed and tested a new assembly method, called GenBrick (hyperlink to GenBrick). Finally, we wanted to see how our manipulations might affect cell metabolism, by combining a modular model of the whole cell (hyperlink to modelling), to which different pathways can be slotted in.

|

| | | |

|

| This iGEM team has been funded by the MSD Scottish Life Sciences Fund. The opinions expressed by this iGEM team are those of the team members and do not necessarily represent those of MSD | |||||

"

"