|

|

| (34 intermediate revisions not shown) |

| Line 18: |

Line 18: |

| | /*Add favicon*/ $("link[rel='shortcut icon']").remove(); $("head").append("<link rel='shortcut icon' type='image/png' href='https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/6/6d/Uppsalas-cow-con.png'>"); }); | | /*Add favicon*/ $("link[rel='shortcut icon']").remove(); $("head").append("<link rel='shortcut icon' type='image/png' href='https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/6/6d/Uppsalas-cow-con.png'>"); }); |

| | </script> | | </script> |

| | + | |

| | + | <link href="https://2013.igem.org/Team:Uppsala/lightbox-css-code.css?action=raw&ctype=text/css" type="text/css" rel="stylesheet"> |

| | + | |

| | + | <script src="https://2013.igem.org/Team:Uppsala/jquery-code.js?action=raw&ctype=text/javascript" type="text/javascript"></script> |

| | + | |

| | + | <script src="https://2013.igem.org/Team:Uppsala/lightbox-code.js?action=raw&ctype=text/javascript" type="text/javascript"></script> |

| | </head> | | </head> |

| | | | |

| Line 63: |

Line 69: |

| | <li><a href="https://2013.igem.org/Team:Uppsala/metabolic-engineering">Metabolic engineering</a> | | <li><a href="https://2013.igem.org/Team:Uppsala/metabolic-engineering">Metabolic engineering</a> |

| | <ul> | | <ul> |

| - | <li><a href="https://2013.igem.org/Team:Uppsala/p-coumaric-acid">P-coumaric acid</a></li> | + | <li><a href="https://2013.igem.org/Team:Uppsala/p-coumaric-acid">p-Coumaric acid</a></li> |

| | <li><a href="https://2013.igem.org/Team:Uppsala/resveratrol">Resveratrol</a></li> | | <li><a href="https://2013.igem.org/Team:Uppsala/resveratrol">Resveratrol</a></li> |

| | <li><a href="https://2013.igem.org/Team:Uppsala/lycopene">Lycopene</a></li> | | <li><a href="https://2013.igem.org/Team:Uppsala/lycopene">Lycopene</a></li> |

| Line 84: |

Line 90: |

| | <li><a href="https://2013.igem.org/Team:Uppsala/modeling" id="list_type1"><img class="nav-text" src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/6/63/Uppsala2013_Modeling.png"></a> | | <li><a href="https://2013.igem.org/Team:Uppsala/modeling" id="list_type1"><img class="nav-text" src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/6/63/Uppsala2013_Modeling.png"></a> |

| | <ul> | | <ul> |

| - | <li><a href="https://2013.igem.org/Team:Uppsala/P-Coumaric-acid-pathway">P-Coumaric acid</a></li> | + | <li><a href="https://2013.igem.org/Team:Uppsala/P-Coumaric-acid-pathway">Kinetic model</a></li> |

| | <li><a href="https://2013.igem.org/Team:Uppsala/modeling-tutorial">Modeling tutorial </a></li> | | <li><a href="https://2013.igem.org/Team:Uppsala/modeling-tutorial">Modeling tutorial </a></li> |

| | + | |

| | + | <li><a href="https://2013.igem.org/Team:Uppsala/toxicity-model">Toxicity model</a></li> |

| | </ul></li> | | </ul></li> |

| | <li><a href="https://2013.igem.org/Team:Uppsala/parts" id="list_type2"><img class="nav-text" src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/e/eb/Uppsala2013_parts.png"></a></li> | | <li><a href="https://2013.igem.org/Team:Uppsala/parts" id="list_type2"><img class="nav-text" src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/e/eb/Uppsala2013_parts.png"></a></li> |

| Line 94: |

Line 102: |

| | <li><a href="https://2013.igem.org/Team:Uppsala/carotenoid-group">Carotenoid group</a></li> | | <li><a href="https://2013.igem.org/Team:Uppsala/carotenoid-group">Carotenoid group</a></li> |

| | <li><a href="https://2013.igem.org/Team:Uppsala/chassi-group">Chassi group</a></li> | | <li><a href="https://2013.igem.org/Team:Uppsala/chassi-group">Chassi group</a></li> |

| | + | <li><a href="https://2013.igem.org/Team:Uppsala/advisors">Advisors</a></li> |

| | | | |

| | </ul></li> | | </ul></li> |

| Line 103: |

Line 112: |

| | <li><a href="https://2013.igem.org/Team:Uppsala/public-opinion">Public opinion </a></li> | | <li><a href="https://2013.igem.org/Team:Uppsala/public-opinion">Public opinion </a></li> |

| | <li><a href="https://2013.igem.org/Team:Uppsala/Outreach">High school & media </a></li> | | <li><a href="https://2013.igem.org/Team:Uppsala/Outreach">High school & media </a></li> |

| - | | + | <li><a href="https://2013.igem.org/Team:Uppsala/bioart">BioArt</a></li> |

| | + | <li><a href="https://2013.igem.org/Team:Uppsala/LactonutritiousWorld">A LactoWorld</a></li> |

| | + | <li><a href="https://2013.igem.org/Team:Uppsala/killswitches">Killswitches</a></li> |

| | + | <li><a href="https://2013.igem.org/Team:Uppsala/realization">Patent</a></li> |

| | </ul></li> | | </ul></li> |

| - | <li><a href="https://2013.igem.org/Team:Uppsala/attribution" id="list_type4"><img class="nav-text" src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/5/5d/Uppsala2013_Attributions.png"></a> | + | <li><a href="https://2013.igem.org/Team:Uppsala/attribution" id="list_type4"><img class="nav-text" src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/5/5d/Uppsala2013_Attributions.png"></a></li> |

| - | <ul>

| + | |

| - | <li><a href="https://2013.igem.org/Team:Uppsala/collaboration">Collaboration</a></li>

| + | |

| - | </ul></li>

| + | |

| | <li><a href="https://2013.igem.org/Team:Uppsala/notebook" id="list_type3"><img class="nav-text" src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/3/36/Uppsala2013_Notebook.png"></a> | | <li><a href="https://2013.igem.org/Team:Uppsala/notebook" id="list_type3"><img class="nav-text" src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/3/36/Uppsala2013_Notebook.png"></a> |

| | <ul> | | <ul> |

| | <li><a href="https://2013.igem.org/Team:Uppsala/safety-form">Safety form</a></li> | | <li><a href="https://2013.igem.org/Team:Uppsala/safety-form">Safety form</a></li> |

| | + | <li><a href="https://2013.igem.org/Team:Uppsala/protocols">Protocols</a></li> |

| | </ul></li> | | </ul></li> |

| | </ul> | | </ul> |

| Line 120: |

Line 130: |

| | <div id="main_content"> <!-- Put content here --> | | <div id="main_content"> <!-- Put content here --> |

| | <img id="p-com_head" src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/0/02/20130924122324%21Uppsala2013_P-coumaric_acid3.png"> | | <img id="p-com_head" src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/0/02/20130924122324%21Uppsala2013_P-coumaric_acid3.png"> |

| - | <h1 class="main-title">P-Coumaric Acid</h1> | + | <h1 class="main-title">p-Coumaric Acid</h1> |

| | | | |

| | <div id="p-com-text1"> | | <div id="p-com-text1"> |

| Line 126: |

Line 136: |

| | <h1>Opening up the phenylpropanoid pathway to iGEM</h1> | | <h1>Opening up the phenylpropanoid pathway to iGEM</h1> |

| | | | |

| - | <p>The phenylpropanoid pathway metabolites, which starts with the aminoacids tyrosine or phenylalanine as precursors has many important health aspects. Tyrosine ammonia lyase produces p-coumaric acid from tyrosine. We have searched the parts registry of a working and characterized tyrosine ammonia lyase, but all earlier iGEM attempts showed no characterization of availability whatsoever. That is why we decided to make a fully working and characterized biobrick of tyrosine ammonia lyase. By using a new to iGEM bacterial version of tyrosine ammonia lyase, we will open up the diverse metabolic pathway of flavonoids, anthocyanins, and stilbenes, to name a few. <sup><a href="#l1">[1]</a></sup> In this project, we will try to produce the antioxidants p-coumaric acid and resveratrol.</p> | + | <p>The phenylpropanoid pathway metabolites, which starts with the aminoacids tyrosine or phenylalanine as precursors has many important health aspects. Tyrosine ammonia lyase produces p-coumaric acid from tyrosine. We have searched the parts registry of a working and characterized tyrosine ammonia lyase, but all earlier iGEM attempts showed no characterization or availability whatsoever. That is why we decided to make a fully working and characterized biobrick of tyrosine ammonia lyase. By using a new to iGEM bacterial version of tyrosine ammonia lyase, we will open up the diverse metabolic pathway of flavonoids, anthocyanins, and stilbenes, to name a few. <sup><a href="#l1">[1]</a></sup> In this project, we will try to produce the antioxidants p-coumaric acid and resveratrol.</p> |

| | | | |

| | </div> | | </div> |

| | | | |

| | <table id="p-com-text2"> | | <table id="p-com-text2"> |

| - | <h1>P-coumaric acid</h1> | + | <h1>p-Coumaric acid</h1> |

| | <td id="p-text"> | | <td id="p-text"> |

| | | | |

| - | <p>P-coumaric acid is an antioxidant with many beneficial health aspects.It has been shown that it reduces the risk of one of our greatest modern western diseases, atherosclerosis.<sup><a href="#l2">[2]</a></sup> It has also been shown to reduce the risk of stomach cancer. <sup><a href="#l3">[3]</a></sup> That is why we think this is a very important ingredient in our probiotic bacteria.</p> | + | <p>p-Coumaric acid is an antioxidant with many beneficial health aspects.It has been shown that it reduces the risk of one of our greatest modern western diseases, atherosclerosis.<sup><a href="#l2">[2]</a></sup> It has also been shown to reduce the risk of stomach cancer. <sup><a href="#l3">[3]</a></sup> That is why we think this is a very important ingredient in our probiotic bacteria.</p> |

| | </td> | | </td> |

| - | <td><img id="coumaric_acid" src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/8/82/Uppsala_coumaric_acid.jpg"></td> | + | <td><a href="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/8/82/Uppsala_coumaric_acid.jpg" data-lightbox="roadtrip"><img id="coumaric_acid" src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/8/82/Uppsala_coumaric_acid.jpg"></a></td> |

| | </table> | | </table> |

| | | | |

| Line 143: |

Line 153: |

| | <p> | | <p> |

| | Tyrosine ammonia lyase (TAL) from rhodobacter sphaeroides was obtained from J.Conrado et al.<sup><a href="#l3">[4]</a></sup> | | Tyrosine ammonia lyase (TAL) from rhodobacter sphaeroides was obtained from J.Conrado et al.<sup><a href="#l3">[4]</a></sup> |

| - | The previous versions used in iGEM have all been from eukaryotic species. We biobricked TAL with the ribosome binding site B0034 and overhangs in a single pcr with primer overhangs. We also made a version with 6-HIS-tag for enzyme expression analysis. TAL was also mutagenized to remove illegal Not1 site. We verify all of our genetical constructs with sequencing. | + | The previous uncharacterized versions used in iGEM have all been of eukaryotic origin. We biobricked TAL with the ribosome binding site B0034 and overhangs in a single PCR with primer overhangs. We also made a version with 6-HIS-tag for enzyme expression analysis. TAL was also mutagenized to remove an illegal Not1 site. We verified all of our genetic constructs with sequencing. |

| | <br><br> | | <br><br> |

| - | We have expressed TAL in e-coli DH5alpha and E-coli nissle, a probiotic e-coli obtained from Trieste iGEM 2012. TAL will also be characterized in lactobacillus, by transforming the construct with our shuttle vector. | + | We have expressed TAL in E. coli DH5alpha and E. coli nissle, a probiotic E. coli obtained from Trieste iGEM 2012. TAL will also be characterized in lactobacillus, by transforming the construct with our shuttle vector. |

| - | This construct can also be used to produce the precursor for our resveratrol. | + | This construct can also be used to produce the precursor for our resveratrol producing bacteria. |

| | </p> | | </p> |

| | </div> | | </div> |

| - | <img class="hej" src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/9/9a/Uppsala_TAL.png"> | + | <a href="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/9/9a/Uppsala_TAL.png" data-lightbox="roadtrip"><img class="hej" src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/9/9a/Uppsala_TAL.png"></a> |

| | <h1>Results</h1> | | <h1>Results</h1> |

| | | | |

| | <h3>Summary</h3> | | <h3>Summary</h3> |

| - | <p>We managed to clone out and biobrick tyrosine ammonia lyase and verify the biobrick by sequencing. Also we did succeful characterization on this part, showing that it works as expected. We managed to express our enzyme and detect it in a western blot, and also detect our metabolite in both spectrophotometry and hplc. The biobrick was characterized in e-coli d5halpha and e-coli nissle. For detailed information about the characterisation methods, see the <a href="https://2013.igem.org/Team:Uppsala/protocols">protocol</a> section. </p> | + | <p>We managed to clone out and biobrick tyrosine ammonia lyase and verify the biobrick by sequencing. We have also done successful characterization of this part, showing that it works as expected. We managed to express our enzyme and detect it in a western blot, and also detected our metabolite in both spectrophotometry and HPLC. The biobrick was characterized in E. coli d5alpha and E. coli nissle. For detailed information about the characterization experiments, see the <a href="https://2013.igem.org/Team:Uppsala/protocols">protocol</a> section. </p> |

| | | | |

| | | | |

| | <h3>Biobrick</h3> | | <h3>Biobrick</h3> |

| | We succeded in the cloning and sequencing of our biobrick, Tyrosine ammonia lyase from | | We succeded in the cloning and sequencing of our biobrick, Tyrosine ammonia lyase from |

| - | rhodobacter sphaeroides with the RBS B0034 that should work in various organisms, lactobacillus | + | rhodobacter sphaeroides with the RBS B0034. This construct was designed to work in various organisms, such as lactobacillus and E. coli. Sequencing was done at GATC biotech and Uppsala Genome center using Sanger |

| - | and e-coli. Sequencing was done at GATC biotech and Uppsala Genome center using sanger | + | |

| | sequencing. <br><br> | | sequencing. <br><br> |

| | Tyrosine ammonia lyase with rbs: <a href="http://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K1033000">BBa_K1033000</a><br><br> | | Tyrosine ammonia lyase with rbs: <a href="http://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K1033000">BBa_K1033000</a><br><br> |

| | | | |

| | <h3>Western blot</h3> | | <h3>Western blot</h3> |

| - | We also succeeded in expressing the enzyme tyrosine ammonia-lyase (TAL) in e-coli. <br><br> | + | We also succeeded in expressing the enzyme tyrosine ammonia-lyase (TAL) in E. coli. <br><br> |

| - | To enable the detection of this protein by anti-his antibodies, 6-histidine tags was incorporated in the | + | To enable the detection of this protein by anti-his antibodies, 6-histidine tags were incorporated in the |

| - | sequence. This way we could detect our enzyme with anti-his antibodies. <br><br> | + | sequence. By doing this we would be able detect our enzyme with anti-his antibodies. <br><br> |

| - | We expressed our protein with a promotor working in both lactobacillus and e-coli. This way, we can | + | We expressed our protein with a promoter working in both lactobacillus and E. coli. We did this to later be able to transfer this TAL construct to lactobacilli strains.<br><br> |

| - | easily transfer TAL to lactobacillus later on.<br><br>

| + | The size of our protein was calculated using ProtParam<sup><a href="#l3">[5]</a></sup> to 54.9 kDA.<br><br> |

| - | The size of our protein was calculated using ProtParam<sup><a herf="#l3">[5]</a></sup>, 54.9 kDA.<br><br> | + | |

| | | | |

| - | <div class="pc-wblot"><img class="results_pic_wblot_pc" src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/igem.org/8/8d/Uppsala_pic_coumaric_wblot.png"><div> | + | <div class="pc-wblot"><a href="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/igem.org/8/8d/Uppsala_pic_coumaric_wblot.png" data-lightbox="roadtrip" title="1. Positive control<br> |

| | + | 2. TAL with CP8 promoter<br> |

| | + | 3. TAL with J23110 promoter<br> |

| | + | 4. Negative control<br>"><img class="results_pic_wblot_pc" src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/igem.org/8/8d/Uppsala_pic_coumaric_wblot.png"></a><div> |

| | 1. Positive control<br> | | 1. Positive control<br> |

| - | 2. TAL with Cp8 promotor<br> | + | 2. TAL with CP8 promoter<br> |

| - | 3. TAL with J23110 promotor<br> | + | 3. TAL with J23110 promoter<br> |

| | 4. Negative control<br></div> | | 4. Negative control<br></div> |

| | </div> | | </div> |

| - | <p id="fig-text"><i><b>Figure 1:</b>SDS-page and western blot. Expression of Tyrosine ammonia lyase with constitutive promotors. The negative control is empty, showing that there is no natural protein in e-coli with the same attributes.</i><br><br></p> | + | <p id="fig-text"><i><b>Figure 1: </b>SDS-page and western blot. Expression of Tyrosine ammonia lyase with constitutive promoters in E. coli. The negative control has no bands, showing that there is no natural protein in wildtype E. coli with the same attributes. The positive control shows that the staining has worked. The two sample lanes 2 and 3 have clear bands around 55 kDA which suggests that these two recombinant E. coli strains produce the TAL protein.</i><br><br></p> |

| | | | |

| | <h3>Spectrophotometry</h3> | | <h3>Spectrophotometry</h3> |

| - | As the next step, we have made a spectrophotometric assay of our metabolite p-coumaric acid produced by e-coli. By using n-octanol and a two-phase extraction, we were able to extract our metabolite from the lb medium and bacteria. This way we could characterize our biobrick on spectrophotometer. The positive control we used had a final p-coumaric concentration of 500 µl. In our spectrophotometry we can see that we have a somewhat lower concentration after 48 hours of stationary phase incubation.<br><br> | + | As the next step, we have made a spectrophotometric assay of our metabolite p-coumaric acid produced by E. coli. By using n-octanol and a two-phase extraction, we were able to extract our metabolite from the LB medium incubated with TAl producing bacteria. After this purification step, we were able to characterize our biobrick on a spectrophotometer. The positive control we used had a final p-coumaric concentration of 500 µl. The spectrophotometry experiments show that there is a somewhat lower concentration in the sample extracts after 48 hours of stationary phase incubation compared to the positive control.<br><br> |

| | | | |

| - | The absorbance spectra of extracts from bacterial cultures grown at stationary phase for 48 hours were collected and the concentration of p-coumaric acid was calculated from the absorbance spectra in an ordinary least squares manner with a <a>MATLAB-script</a>. The concentrations of p-coumaric acid in the cultures were: 228 µM for pSB3K3-J23101-TAL, 158 µM for pSB3K3-J23110-TAL and 311 µM for pSB3K3-CP8-TAL (spectrum shown in figure 2 below).<br><br> | + | The absorbance spectra of extracts from bacterial cultures grown at stationary phase for 48 hours were collected and the concentration of p-coumaric acid was calculated from the absorbance spectra in an ordinary least squares manner with a <a href="https://2013.igem.org/Team:Uppsala/P-Coumaric-acid-pathway#Mat">MATLAB script</a>. The concentrations of p-coumaric acid in the cultures were: 228 µM for pSB3K3-J23101-TAL, 158 µM for pSB3K3-J23110-TAL and 311 µM for pSB3K3-CP8-TAL (spectra shown in figure 2 below).<br><br> |

| - | <img class="results_pic_wblot_pc" src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/igem.org/d/da/Uppsala_pic_coumaric_Spectrophotometry.png"> | + | |

| - | <p id="fig-text"><i><b>Figure 2:</b>Absorbance spectra of extracts collected from bacterial cultures of strain pSB3K3-CP8-TAL. Samples were collected 21 h and 48 h after 30 °C incubation. Negative control is an extract from a strain with no TAL gene on the transformed plasmid. The positive control is an extract on a culture of the same strain as the negative control but with added p-coumaric acid to a concentration of 500 µM before extraction.</i><br><br></p> | + | <a href="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/7/7e/SpectroA.png" data-lightbox="roadtrip2" title="Absorbance spectra of n-octanol extracts collected from bacterial cultures. Samples were collected 21 h and 48 h after 30 °C incubation. The negative control is an extract from a strain with no TAL gene on the transformed plasmid. The positive control is an extract of a culture of the same strain as the negative control but with added p-coumaric acid to a concentration of 500 µM before extraction. P-coumaric acid absorbance spectra has two peaks. The one around 305 nm is preferable to detect because of background noise from components found in LB that do transfer to the octanol phase in the extraction. (a) Spectra from the strain with TAL CDS with promoter J23110. (b) Spectra from the strain with TAL CDS with promoter CP8. (c) Spectra from the strain with TAL CDS with promoter J23101.(d) Standards of pure p-coumaric acid solved in n-octanol. The standards show that p-coumaric acid has a broad peak in absorbance around 305 nm."><img class="results_pic_wblot_pc" src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/7/7e/SpectroA.png"></a> |

| | + | |

| | + | <a href="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/igem.org/d/da/Uppsala_pic_coumaric_Spectrophotometry.png" data-lightbox="roadtrip2" title="Absorbance spectra of n-octanol extracts collected from bacterial cultures. Samples were collected 21 h and 48 h after 30 °C incubation. The negative control is an extract from a strain with no TAL gene on the transformed plasmid. The positive control is an extract of a culture of the same strain as the negative control but with added p-coumaric acid to a concentration of 500 µM before extraction. P-coumaric acid absorbance spectra has two peaks. The one around 305 nm is preferable to detect because of background noise from components found in LB that do transfer to the octanol phase in the extraction. (a) Spectra from the strain with TAL CDS with promoter J23110. (b) Spectra from the strain with TAL CDS with promoter CP8. (c) Spectra from the strain with TAL CDS with promoter J23101.(d) Standards of pure p-coumaric acid solved in n-octanol. The standards show that p-coumaric acid has a broad peak in absorbance around 305 nm."><img class="results_pic_wblot_pc" src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/igem.org/d/da/Uppsala_pic_coumaric_Spectrophotometry.png"></a> |

| | + | |

| | + | <a href="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/0/0d/SpectroC.png" data-lightbox="roadtrip2" title="Absorbance spectra of n-octanol extracts collected from bacterial cultures. Samples were collected 21 h and 48 h after 30 °C incubation. The negative control is an extract from a strain with no TAL gene on the transformed plasmid. The positive control is an extract of a culture of the same strain as the negative control but with added p-coumaric acid to a concentration of 500 µM before extraction. P-coumaric acid absorbance spectra has two peaks. The one around 305 nm is preferable to detect because of background noise from components found in LB that do transfer to the octanol phase in the extraction. (a) Spectra from the strain with TAL CDS with promoter J23110. (b) Spectra from the strain with TAL CDS with promoter CP8. (c) Spectra from the strain with TAL CDS with promoter J23101.(d) Standards of pure p-coumaric acid solved in n-octanol. The standards show that p-coumaric acid has a broad peak in absorbance around 305 nm."><img class="results_pic_wblot_pc" src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/0/0d/SpectroC.png"></a> |

| | + | |

| | + | <a href="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/1/1f/SpectropCoumStandard_uppsala.png" data-lightbox="roadtrip2" title="Absorbance spectra of n-octanol extracts collected from bacterial cultures. Samples were collected 21 h and 48 h after 30 °C incubation. The negative control is an extract from a strain with no TAL gene on the transformed plasmid. The positive control is an extract of a culture of the same strain as the negative control but with added p-coumaric acid to a concentration of 500 µM before extraction. P-coumaric acid absorbance spectra has two peaks. The one around 305 nm is preferable to detect because of background noise from components found in LB that do transfer to the octanol phase in the extraction. (a) Spectra from the strain with TAL CDS with promoter J23110. (b) Spectra from the strain with TAL CDS with promoter CP8. (c) Spectra from the strain with TAL CDS with promoter J23101.(d) Standards of pure p-coumaric acid solved in n-octanol. The standards show that p-coumaric acid has a broad peak in absorbance around 305 nm."><img class="results_pic_wblot_pc" src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/1/1f/SpectropCoumStandard_uppsala.png"></a> |

| | + | |

| | + | <p id="fig-text"><i><b>Figure 2:</b> Absorbance spectra of n-octanol extracts collected from bacterial cultures. Samples were collected 21 h and 48 h after 30 °C incubation. The negative control is an extract from a strain with no TAL gene on the transformed plasmid. The positive control is an extract of a culture of the same strain as the negative control but with added p-coumaric acid to a concentration of 500 µM before extraction. P-coumaric acid absorbance spectra has two peaks. The one around 305 nm is preferable to detect because of background noise from components found in LB that do transfer to the octanol phase in the extraction. (a) Spectra from the strain with TAL CDS with promoter J23110. (b) Spectra from the strain with TAL CDS with promoter CP8. (c) Spectra from the strain with TAL CDS with promoter J23101.(d) Standards of pure p-coumaric acid solved in n-octanol. The standards show that p-coumaric acid has a broad peak in absorbance around 305 nm.</i><br><br></p> |

| | | | |

| | <h3>High pressure liquid chromatography</h3> | | <h3>High pressure liquid chromatography</h3> |

| - | We also saw in our hplc that we have succefull production of p-coumaric acid in e-coli. The next step will be to transfer the genes with our shuttle vector to express them in lactobacillus.) </p><br><br>

| + | HPLC characterization further proved that we have succefull production of p-coumaric acid in E. coli. The next step will be to transfer the genes to our shuttle vector to express them in lactobacillus. </p><br><br> |

| | | | |

| | | | |

| | <table> | | <table> |

| - | <tr><td class="pic_col_results_pc"><img class="results_pic_pc" src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/e/ef/Uppsala_char_coumaric-acid_plasmid.png"></td><td class="fig-text"><i><b>Figure 3.</b> Graph showing the HPLC result of a sample prepared from e coli expressing tyrosine ammonia lyase. Reverse phase HPLC with a C18 matrix was used. The peak for p-coumaric acid can be seen ~9 min, as shown by the standard sample below.</i> </td></tr> | + | <tr><td class="pic_col_results_pc"> |

| - | <tr><td class="pic_col_results_pc"><img class="results_pic_pc" src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/b/be/Uppsala_char_coumaric-acid_standard.png"></td><td class="fig-text"><i><b>Figure 4.</b> Graph showing the HPLC result of a sample standard with p-coumaric acid</i></td></tr> | + | <a href="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/e/ef/Uppsala_char_coumaric-acid_plasmid.png" data-lightbox="roadtrip3" title="Graph showing the HPLC result of an octanol extract prepared from E. coli expressing tyrosine ammonia lyase. Reverse phase HPLC with a C18 matrix was used. A mix of acetate buffer and acetonitrile were used as mobile phase in this gradient elution experiment. The absorbance of the eluate was detected at 303 nm. The peak for p-coumaric acid can be seen ~9 min: the same retention time as the standard sample below."><img class="results_pic_pc" src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/e/ef/Uppsala_char_coumaric-acid_plasmid.png"></a> |

| - | <tr><td class="pic_col_results_pc"><img class="results_pic_pc" src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/4/4f/Uppsala_char_coumaric-acid_blank.png"></td><td class="fig-text"><i><b>Figure 5.</b> E-coli culture injected to the hplc without our biobrick tyrosine ammonia lyase. Here we can see that there is originally no peak at 9 minutes.</i> </td></tr> | + | </td><td class="fig-text"><i><b>Figure 3.</b> Graph showing the HPLC result of an octanol extract prepared from E. coli expressing tyrosine ammonia lyase. Reverse phase HPLC with a C18 matrix was used. A mix of acetate buffer and acetonitrile were used as mobile phase in this gradient elution experiment. The absorbance of the eluate was detected at 303 nm. The peak for p-coumaric acid can be seen ~9 min: the same retention time as the standard sample below.</i> </td></tr> |

| | + | <tr><td class="pic_col_results_pc"> |

| | + | <a href="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/b/be/Uppsala_char_coumaric-acid_standard.png" data-lightbox="roadtrip3" title="Graph showing the HPLC result of a standard sample with pure p-coumaric acid (50 µM) in n-octanol."><img class="results_pic_pc" src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/b/be/Uppsala_char_coumaric-acid_standard.png"></a> |

| | + | </td><td class="fig-text"><i><b>Figure 4.</b> Graph showing the HPLC result of a standard sample with pure p-coumaric acid (50 µM) in n-octanol.</i></td></tr> |

| | + | <tr><td class="pic_col_results_pc"> |

| | + | <a href="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/4/4f/Uppsala_char_coumaric-acid_blank.png" data-lightbox="roadtrip3" title="HPLC chromatogram of a n-octanol extract from a E. coli culture without our biobrick tyrosine ammonia lyase. No peak at 9 minutes can be detected in this negative control."><img class="results_pic_pc" src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/4/4f/Uppsala_char_coumaric-acid_blank.png"></a> |

| | + | </td><td class="fig-text"><i><b>Figure 5.</b> HPLC chromatogram of a n-octanol extract from a E. coli culture without our biobrick tyrosine ammonia lyase. No peak at 9 minutes can be detected in this negative control.</i> </td></tr> |

| | </table> | | </table> |

| | | | |

| Line 201: |

Line 226: |

| | | | |

| | <p class="reference"> | | <p class="reference"> |

| - | <a name="l1">[1]</a>Zhixion Xue et al, Identification and functional expression of tyrosine ammonia-lyase and its mutants from the photosynthetic bacterium rhodobacter sphaeroides, J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol (2007) 34:599-604<br> | + | <a name="l1">[1]</a>Zhixion Xue et al, Identification and functional expression of tyrosine ammonia-lyase and its mutants from the photosynthetic bacterium rhodobacter sphaeroides, J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol (2007) 34:599-604<br><br> |

| - | <a name="l2">[2]</a> Lun-Yi Zang et al, Effect of antioxidant protection by p-coumaric acid on low-density lipoprotein cholesterol oxidation, Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2000 Oct;279(4):C954-60.<br> | + | <a name="l2">[2]</a> Lun-Yi Zang et al, Effect of antioxidant protection by p-coumaric acid on low-density lipoprotein cholesterol oxidation, Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2000 Oct;279(4):C954-60.<br><br> |

| - | <a name="l3">[3]</a>Lynnette R. Ferguson, Shuo-tun Zhu, Philip J. Harris, Antioxidant and antigenotoxic effects of plant cell wall hydroxycinnamic acids in cultured HT-29 cells, Issue, Molecular Nutrition & Food Research, Volume 49, Issue 6, pages 585–593, June 2005<br> | + | <a name="l3">[3]</a>Lynnette R. Ferguson, Shuo-tun Zhu, Philip J. Harris, Antioxidant and antigenotoxic effects of plant cell wall hydroxycinnamic acids in cultured HT-29 cells, Issue, Molecular Nutrition & Food Research, Volume 49, Issue 6, pages 585–593, June 2005<br><br> |

| - | <a name="l3">[4]</a>Robert J. Conrado et al, DNA guided assembly of biosynthetic pathways promotes improved catalytic effiency. Nucleic Acids Research , 2012, Vol 40 NO 4, 1879-1889<br> | + | <a name="l3">[4]</a>Robert J. Conrado et al, DNA guided assembly of biosynthetic pathways promotes improved catalytic effiency. Nucleic Acids Research , 2012, Vol 40 NO 4, 1879-1889<br><br> |

| | <a name="l3">[5]</a> <a href="http://web.expasy.org/protparam/ ">http://web.expasy.org/protparam/</a> | | <a name="l3">[5]</a> <a href="http://web.expasy.org/protparam/ ">http://web.expasy.org/protparam/</a> |

| | </p> | | </p> |

| Line 213: |

Line 238: |

| | | | |

| | <div id="bottom-pic"> | | <div id="bottom-pic"> |

| - | <img class="bottom-pic" src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/a/aa/Bottom_picture.png">

| + | |

| | </div> | | </div> |

| | | | |

p-Coumaric Acid

Opening up the phenylpropanoid pathway to iGEM

The phenylpropanoid pathway metabolites, which starts with the aminoacids tyrosine or phenylalanine as precursors has many important health aspects. Tyrosine ammonia lyase produces p-coumaric acid from tyrosine. We have searched the parts registry of a working and characterized tyrosine ammonia lyase, but all earlier iGEM attempts showed no characterization or availability whatsoever. That is why we decided to make a fully working and characterized biobrick of tyrosine ammonia lyase. By using a new to iGEM bacterial version of tyrosine ammonia lyase, we will open up the diverse metabolic pathway of flavonoids, anthocyanins, and stilbenes, to name a few. [1] In this project, we will try to produce the antioxidants p-coumaric acid and resveratrol.

p-Coumaric acid

p-Coumaric acid is an antioxidant with many beneficial health aspects.It has been shown that it reduces the risk of one of our greatest modern western diseases, atherosclerosis.[2] It has also been shown to reduce the risk of stomach cancer. [3] That is why we think this is a very important ingredient in our probiotic bacteria.

|

|

Methods

Tyrosine ammonia lyase (TAL) from rhodobacter sphaeroides was obtained from J.Conrado et al.[4]

The previous uncharacterized versions used in iGEM have all been of eukaryotic origin. We biobricked TAL with the ribosome binding site B0034 and overhangs in a single PCR with primer overhangs. We also made a version with 6-HIS-tag for enzyme expression analysis. TAL was also mutagenized to remove an illegal Not1 site. We verified all of our genetic constructs with sequencing.

We have expressed TAL in E. coli DH5alpha and E. coli nissle, a probiotic E. coli obtained from Trieste iGEM 2012. TAL will also be characterized in lactobacillus, by transforming the construct with our shuttle vector.

This construct can also be used to produce the precursor for our resveratrol producing bacteria.

Results

Summary

We managed to clone out and biobrick tyrosine ammonia lyase and verify the biobrick by sequencing. We have also done successful characterization of this part, showing that it works as expected. We managed to express our enzyme and detect it in a western blot, and also detected our metabolite in both spectrophotometry and HPLC. The biobrick was characterized in E. coli d5alpha and E. coli nissle. For detailed information about the characterization experiments, see the protocol section.

Biobrick

We succeded in the cloning and sequencing of our biobrick, Tyrosine ammonia lyase from

rhodobacter sphaeroides with the RBS B0034. This construct was designed to work in various organisms, such as lactobacillus and E. coli. Sequencing was done at GATC biotech and Uppsala Genome center using Sanger

sequencing.

Tyrosine ammonia lyase with rbs:

BBa_K1033000

Western blot

We also succeeded in expressing the enzyme tyrosine ammonia-lyase (TAL) in E. coli.

To enable the detection of this protein by anti-his antibodies, 6-histidine tags were incorporated in the

sequence. By doing this we would be able detect our enzyme with anti-his antibodies.

We expressed our protein with a promoter working in both lactobacillus and E. coli. We did this to later be able to transfer this TAL construct to lactobacilli strains.

The size of our protein was calculated using ProtParam

[5] to 54.9 kDA.

1. Positive control

2. TAL with CP8 promoter

3. TAL with J23110 promoter

4. Negative control

Figure 1: SDS-page and western blot. Expression of Tyrosine ammonia lyase with constitutive promoters in E. coli. The negative control has no bands, showing that there is no natural protein in wildtype E. coli with the same attributes. The positive control shows that the staining has worked. The two sample lanes 2 and 3 have clear bands around 55 kDA which suggests that these two recombinant E. coli strains produce the TAL protein.

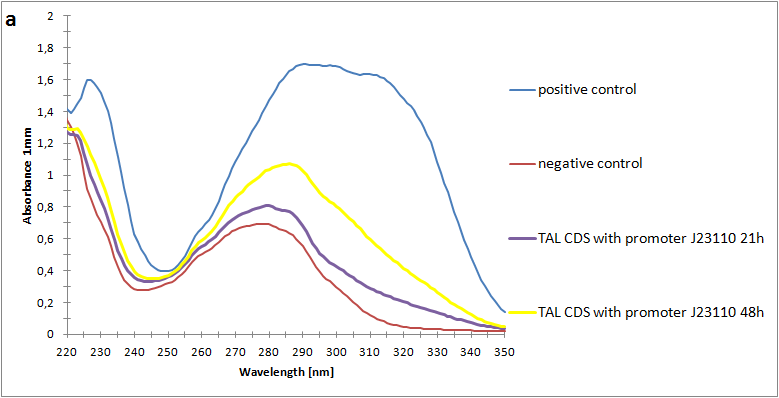

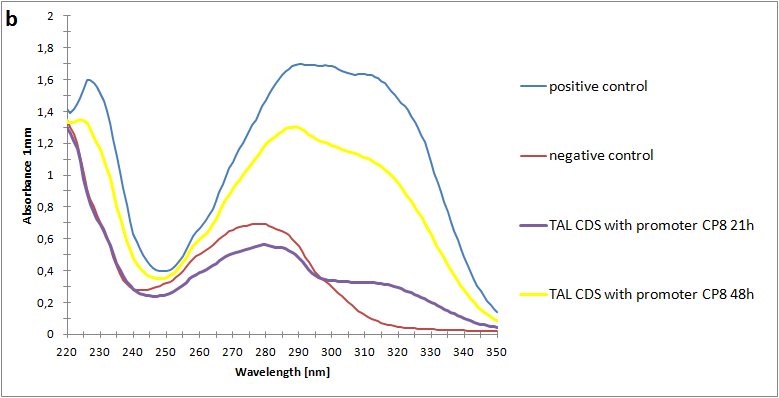

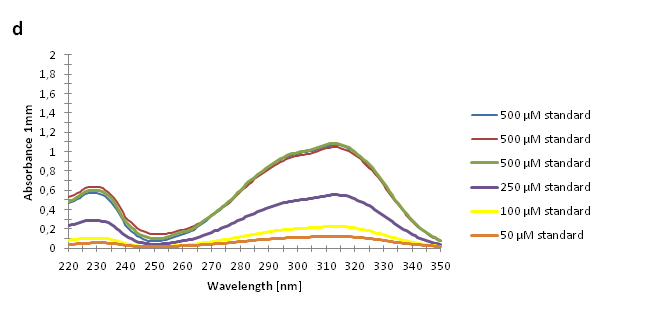

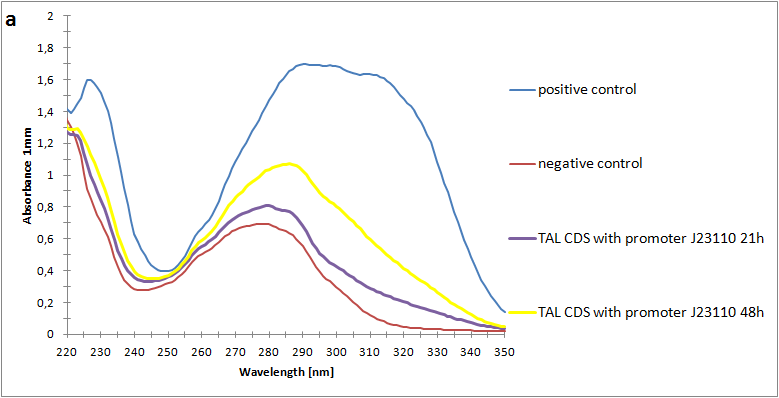

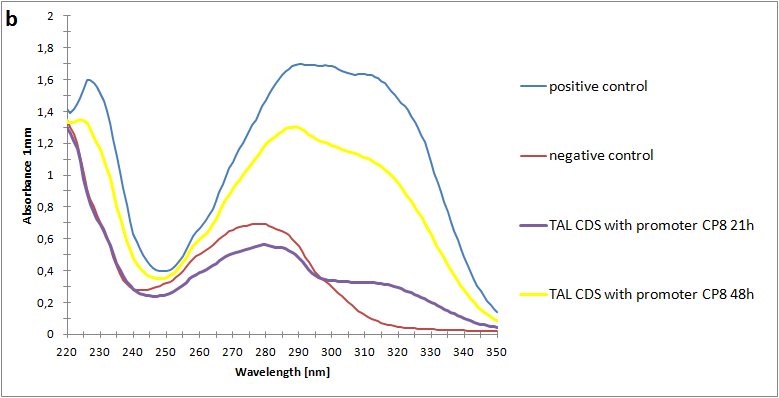

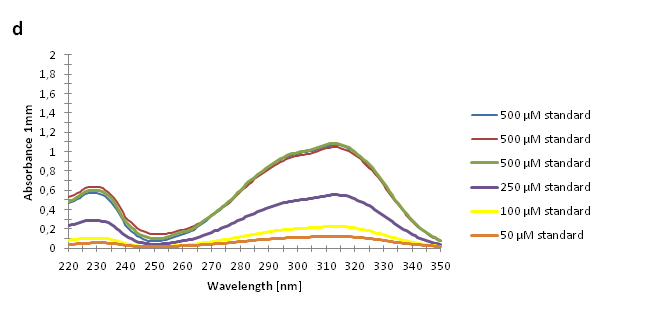

Spectrophotometry

As the next step, we have made a spectrophotometric assay of our metabolite p-coumaric acid produced by E. coli. By using n-octanol and a two-phase extraction, we were able to extract our metabolite from the LB medium incubated with TAl producing bacteria. After this purification step, we were able to characterize our biobrick on a spectrophotometer. The positive control we used had a final p-coumaric concentration of 500 µl. The spectrophotometry experiments show that there is a somewhat lower concentration in the sample extracts after 48 hours of stationary phase incubation compared to the positive control.

The absorbance spectra of extracts from bacterial cultures grown at stationary phase for 48 hours were collected and the concentration of p-coumaric acid was calculated from the absorbance spectra in an ordinary least squares manner with a

MATLAB script. The concentrations of p-coumaric acid in the cultures were: 228 µM for pSB3K3-J23101-TAL, 158 µM for pSB3K3-J23110-TAL and 311 µM for pSB3K3-CP8-TAL (spectra shown in figure 2 below).

Figure 2: Absorbance spectra of n-octanol extracts collected from bacterial cultures. Samples were collected 21 h and 48 h after 30 °C incubation. The negative control is an extract from a strain with no TAL gene on the transformed plasmid. The positive control is an extract of a culture of the same strain as the negative control but with added p-coumaric acid to a concentration of 500 µM before extraction. P-coumaric acid absorbance spectra has two peaks. The one around 305 nm is preferable to detect because of background noise from components found in LB that do transfer to the octanol phase in the extraction. (a) Spectra from the strain with TAL CDS with promoter J23110. (b) Spectra from the strain with TAL CDS with promoter CP8. (c) Spectra from the strain with TAL CDS with promoter J23101.(d) Standards of pure p-coumaric acid solved in n-octanol. The standards show that p-coumaric acid has a broad peak in absorbance around 305 nm.

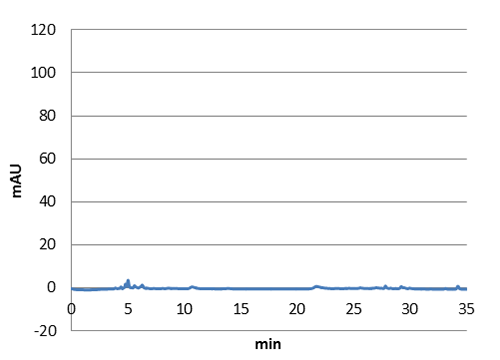

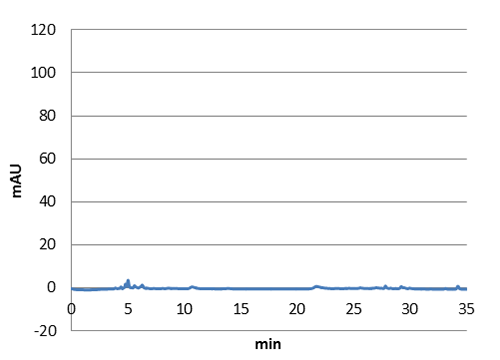

High pressure liquid chromatography

HPLC characterization further proved that we have succefull production of p-coumaric acid in E. coli. The next step will be to transfer the genes to our shuttle vector to express them in lactobacillus.

| Figure 3. Graph showing the HPLC result of an octanol extract prepared from E. coli expressing tyrosine ammonia lyase. Reverse phase HPLC with a C18 matrix was used. A mix of acetate buffer and acetonitrile were used as mobile phase in this gradient elution experiment. The absorbance of the eluate was detected at 303 nm. The peak for p-coumaric acid can be seen ~9 min: the same retention time as the standard sample below. |

| Figure 4. Graph showing the HPLC result of a standard sample with pure p-coumaric acid (50 µM) in n-octanol. |

| Figure 5. HPLC chromatogram of a n-octanol extract from a E. coli culture without our biobrick tyrosine ammonia lyase. No peak at 9 minutes can be detected in this negative control. |

References

[1]Zhixion Xue et al, Identification and functional expression of tyrosine ammonia-lyase and its mutants from the photosynthetic bacterium rhodobacter sphaeroides, J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol (2007) 34:599-604

[2] Lun-Yi Zang et al, Effect of antioxidant protection by p-coumaric acid on low-density lipoprotein cholesterol oxidation, Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2000 Oct;279(4):C954-60.

[3]Lynnette R. Ferguson, Shuo-tun Zhu, Philip J. Harris, Antioxidant and antigenotoxic effects of plant cell wall hydroxycinnamic acids in cultured HT-29 cells, Issue, Molecular Nutrition & Food Research, Volume 49, Issue 6, pages 585–593, June 2005

[4]Robert J. Conrado et al, DNA guided assembly of biosynthetic pathways promotes improved catalytic effiency. Nucleic Acids Research , 2012, Vol 40 NO 4, 1879-1889

[5] http://web.expasy.org/protparam/

"

"