Team:Colombia Uniandes/ChimiProject

From 2013.igem.org

| Line 102: | Line 102: | ||

<html> | <html> | ||

| - | Greenberg, N., and Wingfield, J. C. (1987). Stress and reproduction: Reciprocal relationships. In ‘‘Hormones and Reproduction in Fishes, Amphibians and Reptiles’’ (D. O. Norris and R. E. Jones, Eds.), pp. 461–503. Plenum, New York. | + | |

| - | < | + | <ol> |

| - | Gregory, Lisa. Gross, Timothy. Bolten, Alan. Bjorndal, Karen. Guillette, Louis. (1996) Plasma Corticosterone Concentrations Associated with Acute Captivity Stress in Wild Loggerhead Sea Turtles (Caretta caretta). General and Comparative Endocrinology 104, 312–320 | + | <li>Greenberg, N., and Wingfield, J. C. (1987). Stress and reproduction: Reciprocal relationships. In ‘‘Hormones and Reproduction in Fishes, Amphibians and Reptiles’’ (D. O. Norris and R. E. Jones, Eds.), pp. 461–503. Plenum, New York.</li> |

| - | < | + | |

| - | Judge, M.D. (1969) Environmental Stress and Meat Quality. Journal of Animal Science, 28: 755-760. | + | <li>Gregory, Lisa. Gross, Timothy. Bolten, Alan. Bjorndal, Karen. Guillette, Louis. (1996) Plasma Corticosterone Concentrations Associated with Acute Captivity Stress in Wild Loggerhead Sea Turtles (Caretta caretta). General and Comparative Endocrinology 104, 312–320</li> |

| - | < | + | |

| - | Kirschbaum C, Prussner JC, Stone AA, Federenko I, Gaab J, Lintz D, Schommer N, Hellhammer DH. (1995) Persistent high cortisol responses to repeated psychological stress in a subpopulation of healthy men. Psychosomatic Med 57: 468–474. | + | <li>Judge, M.D. (1969) Environmental Stress and Meat Quality. Journal of Animal Science, 28: 755-760.</li> |

| - | < | + | |

| - | Manson, Georgia J. (2010) Species differences in responses to captivity: stress, welfare and the comparative method. Trends in Ecology and Evolution. Volume 25, Issue 12: Pages 713–721 | + | <li>Kirschbaum C, Prussner JC, Stone AA, Federenko I, Gaab J, Lintz D, Schommer N, Hellhammer DH. (1995) Persistent high cortisol responses to repeated psychological stress in a subpopulation of healthy men. Psychosomatic Med 57: 468–474.</li> |

| - | < | + | |

| - | McEwen, Bruce S. (2007) Physiology and Neurobiology of Stress and Adaptation: Central Role of the Brain. Physiol Rev 87: 873–904 | + | <li>Manson, Georgia J. (2010) Species differences in responses to captivity: stress, welfare and the comparative method. Trends in Ecology and Evolution. Volume 25, Issue 12: Pages 713–721</li> |

| - | < | + | |

| - | McEwen BS, Chattarji S. (2004) Molecular mechanisms of neuroplasticity and pharmacological implications: the example of tianeptine. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 14: 497–502. | + | <li>McEwen, Bruce S. (2007) Physiology and Neurobiology of Stress and Adaptation: Central Role of the Brain. Physiol Rev 87: 873–904</li> |

| - | < | + | |

| - | Morgan, Kathleen. Tromborg, Chris. (2007) Sources of stress in captivity. Applied Animal Behaviour Science. Volume 102: 262–302 | + | <li>McEwen BS, Chattarji S. (2004) Molecular mechanisms of neuroplasticity and pharmacological implications: the example of tianeptine. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 14: 497–502.</li> |

| - | < | + | |

| - | Mirescu C, Gould E. (2006) Stress and adult neurogenesis. Hippocampus16: 233–238 | + | <li>Morgan, Kathleen. Tromborg, Chris. (2007) Sources of stress in captivity. Applied Animal Behaviour Science. Volume 102: 262–302</li> |

| - | < | + | |

| - | Rasgon NL, Kenna HA. (2005) Insulin resistance in depressive disorders and Alzheimer’s disease: revisiting the missing link hypothesis. Neurobiol Aging 26S: S103–S107 | + | <li>Mirescu C, Gould E. (2006) Stress and adult neurogenesis. Hippocampus16: 233–238<li> |

| - | < | + | |

| - | Sachar EJ, Hellman L, Roffwarg HP, Halpern FS, Fukushima DK, Gallagher TF. (1973)Disrupted 24-hour patterns of cortis8ol secretion in psychotic depression. Arch Gen Psychiarty 28: 19–24 | + | <li>Rasgon NL, Kenna HA. (2005) Insulin resistance in depressive disorders and Alzheimer’s disease: revisiting the missing link hypothesis. Neurobiol Aging 26S: S103–S107<li> |

| - | < | + | |

| - | Stephens, D. B. (1980). Stress and its measurement in domestic animals: A review of behavioral and physiological studies under field and laboratory conditions. Adv. Vet Sci. Comp. Med. 24, 179–210. | + | <li>Sachar EJ, Hellman L, Roffwarg HP, Halpern FS, Fukushima DK, Gallagher TF. (1973)Disrupted 24-hour patterns of cortis8ol secretion in psychotic depression. Arch Gen Psychiarty 28: 19–24</li> |

| + | |||

| + | <li>Stephens, D. B. (1980). Stress and its measurement in domestic animals: A review of behavioral and physiological studies under field and laboratory conditions. Adv. Vet Sci. Comp. Med. 24, 179–210.</li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | </ol> | ||

</html> | </html> | ||

Revision as of 22:18, 24 September 2013

ColombiaSuperProjects!

It is widely accepted that exposure to stressors increases secretion of glucocorticoids, cortisol, and corticosterone in a wide variety of gnathostome vertebrates (Stephens, 1980) (Greenberg et al, 1987). Research in animals, have demonstrated that allostatic overload of this hormones and other mediators, resulting from chronic stress, causes atrophy of neurons in the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex; brain regions involved in memory, selective attention and executive function; likewise it causes hypertrophy of neurons in the amygdala, the brain region involved in fear and anxiety as well as aggression (McEwen, 2004). This means that prolonged states of stress may lead to impaired performance in daily activities like learning, decision making and ability to remember; additionally, will cause damage on the amygdala which in turn will increase levels of anxiety and aggression.

Other than neurological, chronic stress in vertebrates is tightly related with pathologies upon metabolism, immunity, reproduction, cardiovascular system and cellular proliferation (Harbuz et al, 1992) (Whittier, 1991); Thus, the dysregulation of cortisol and other mediators that form the allostatic system is likely to play a role in many neurophysiological conditions as well as systemic disorders such as diabetes, impaired reproduction and immunosuppression (Rasgon et al, 2005).

Now a days, approximately 26 billion animals, spanning over 10 000 species, are kept on farms and in zoos, conservation breeding centers, research laboratories and households (Manson, 2010). Taking into account that captivity is a well-known acute stressor (Gregory et al, 1996), if proper conditions of the habitat are not reestablished or defined, acute stress may turn into chronic stress, and consequently lead to problems that are particularly undesirable for animals maintained in captivity; including increased abnormal behavior, increased self-injurious behavior, impaired reproduction and immunosuppression (Morgan et al, 2007). Besides, it’s been demonstrated that stressful conditions on cattle elicit changes in muscle gross morphology in direct proportion with the duration of the stressor, thus a negative effect on the meat quality and other products for human consumption (Judge, 1969).

Likewise, human beings are prone to stressful conditions; Constant exposure to adverse environments like noise and pollution or other lifestyle and social conflicts may cause chronic stress that result, over time, in pathophysiological conditions like atherosclerosis, which can lead to strokes and myocardial infarctions (McEwen, 2007).

Identifying a standardized mechanism that allows an early detection of stress is of high importance in different applications such as animal conservation and human practices such as investigation, medicine, animal breeding and cattle raising. Also, doing the proper characterization of the different types of stress provide insight information about the animal condition and therefore, assist an early diagnosis to prevent acute stress to become chronic.

Nowadays, hormones act as biological markers of stress; In this practices the so called “stress-hormones” such as cortisol in humans and corticosterone in rats are quantified to provide information of stress in animals; Elisa, which is the gold standard for stress determination is highly precise and specific; nevertheless this and most methods that utilize immunoassays are only available for lab practices and involve the manipulation of difficult machinery and specialized procedures that are not available for daily use and which are difficult and expensive to implement in farms, home or other in situ investigations.

We propose a standardized device that’ll detect stress with no need of complex machinery or procedures, but a versatile and easy to use device that can be used by anyone, from a farmer in livestock practices, to yourself at home, to identify if your own pet is held in good conditions and stress-free. The device will sense the presence of one of the “stress hormones”, depending on the specimen used, and compare it to a normal concentration or base line. If the concentration of the hormone sensed is more than usual, the device will send a visual signal to inform the user of the presence of stress. The sensing will be done by a bio-machinery held inside the genetic code of saccharomyces cerevisae. Thus, our genetically manufactured yeast will identify if there’s abnormal presence of the hormone and if the threshold established is reached, elicit the alarm signal using m-cherry.

This project that is aimed to a larger population than the methods previously released, can be used for both formal and informal characterization of stress. In previous examination with members of the laboratory of neuroscience of Andes University, they did recognize the asset of the device to objectively characterize behavior with fewer limitations and costs than with ELISA kit. Besides, interviews with veterinarians provide evidence that the animals held in households and other facilities such as animal breeding centers and farms, often require close observation to avoid negative effects associated with stressed animals.

Although we did recognize that identifying stress in animals is of high important in different fields, we propose to initialize the project with trials on humans mostly because of the vast amount of information on the circadian rhythms and baselines of cortisol (read more here), the main “stress hormone” in humans. Nevertheless, we intent to create a product with different final users, based on personalized needs. This requires a bigger effort as baselines for each specimen shall be established in order to identify the “all or nothing” threshold.

Besides, we propose as future prospects, the possibility to implement various baselines in order to provide a more quantitatively response to the presence of stress, rather than the off-on system originally proposed.

Design: Project Parts!

Glucocorticoid sensor

Our construct

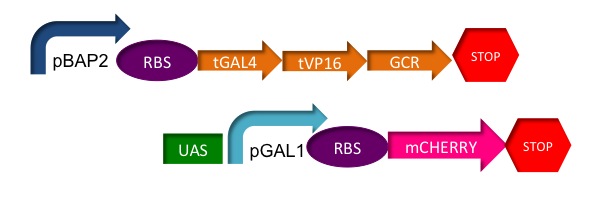

We plan to use the baker's yeast, ''Saccharomyces cerevisiae'', as a chassis for a plasmid which will contain a chimeric protein used as a transactivating factor in a biosensor with a colored reporter.

The Chassis

We chose ''S. cerevisiae'' as the chassis because one of the most important parts of our fusion protein, the glucocorticoid receptor hormone binding domain (GCR HBD) is eukaryotic, therefore we wanted an easy to use, easy to grow, eucaryotic vector to express our protein and build our biosensor.

The Chimera

The glucocorticoid receptor (GCR) from mammals contains three domains necessary for stress hormone related gene transcription, the hormone binding domain (HBD), the DNA binding domain (DNA-BD) and the gene transactivating domain (GTD).

However, for our construct's performance we used a chimeric protein. Just as the mythological creature made from fused parts from a lion, a goat and a snake, we created a chimeric protein using three domains from different organisms.

We used the glucocorticoid receptor hormone binding domain (GCR HBD) which came from a rat to recognize our hormones of interest. However, we replaced the other two domains with the herpesvirus gene transactivating domain (HV-GTD) and the yeast's DNA binding domain from GAL4. These two new domains have the advantage of being already used, characterized and being highly efficient. The HV-GTD is a highly efficient transactivating domain, recognized to be several orders of magnitude better than the GCR-GTD.

Tester Construct

References:

- Greenberg, N., and Wingfield, J. C. (1987). Stress and reproduction: Reciprocal relationships. In ‘‘Hormones and Reproduction in Fishes, Amphibians and Reptiles’’ (D. O. Norris and R. E. Jones, Eds.), pp. 461–503. Plenum, New York.

- Gregory, Lisa. Gross, Timothy. Bolten, Alan. Bjorndal, Karen. Guillette, Louis. (1996) Plasma Corticosterone Concentrations Associated with Acute Captivity Stress in Wild Loggerhead Sea Turtles (Caretta caretta). General and Comparative Endocrinology 104, 312–320

- Judge, M.D. (1969) Environmental Stress and Meat Quality. Journal of Animal Science, 28: 755-760.

- Kirschbaum C, Prussner JC, Stone AA, Federenko I, Gaab J, Lintz D, Schommer N, Hellhammer DH. (1995) Persistent high cortisol responses to repeated psychological stress in a subpopulation of healthy men. Psychosomatic Med 57: 468–474.

- Manson, Georgia J. (2010) Species differences in responses to captivity: stress, welfare and the comparative method. Trends in Ecology and Evolution. Volume 25, Issue 12: Pages 713–721

- McEwen, Bruce S. (2007) Physiology and Neurobiology of Stress and Adaptation: Central Role of the Brain. Physiol Rev 87: 873–904

- McEwen BS, Chattarji S. (2004) Molecular mechanisms of neuroplasticity and pharmacological implications: the example of tianeptine. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 14: 497–502.

- Morgan, Kathleen. Tromborg, Chris. (2007) Sources of stress in captivity. Applied Animal Behaviour Science. Volume 102: 262–302

- Mirescu C, Gould E. (2006) Stress and adult neurogenesis. Hippocampus16: 233–238

-

- Rasgon NL, Kenna HA. (2005) Insulin resistance in depressive disorders and Alzheimer’s disease: revisiting the missing link hypothesis. Neurobiol Aging 26S: S103–S107

-

- Sachar EJ, Hellman L, Roffwarg HP, Halpern FS, Fukushima DK, Gallagher TF. (1973)Disrupted 24-hour patterns of cortis8ol secretion in psychotic depression. Arch Gen Psychiarty 28: 19–24

- Stephens, D. B. (1980). Stress and its measurement in domestic animals: A review of behavioral and physiological studies under field and laboratory conditions. Adv. Vet Sci. Comp. Med. 24, 179–210.

ColombiaSuperProjects!

It is widely accepted that exposure to stressors increases secretion of glucocorticoids, cortisol, and corticosterone in a wide variety of gnathostome vertebrates (Stephens, 1980) (Greenberg et al, 1987). Research in animals, have demonstrated that allostatic overload of this hormones and other mediators, resulting from chronic stress, causes atrophy of neurons in the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex; brain regions involved in memory, selective attention and executive function; likewise it causes hypertrophy of neurons in the amygdala, the brain region involved in fear and anxiety as well as aggression (McEwen, 2004). This means that prolonged states of stress may lead to impaired performance in daily activities like learning, decision making and ability to remember; additionally, will cause damage on the amygdala which in turn will increase levels of anxiety and aggression.

Other than neurological, chronic stress in vertebrates is tightly related with pathologies upon metabolism, immunity, reproduction, cardiovascular system and cellular proliferation (Harbuz et al, 1992) (Whittier, 1991); Thus, the dysregulation of cortisol and other mediators that form the allostatic system is likely to play a role in many neurophysiological conditions as well as systemic disorders such as diabetes, impaired reproduction and immunosuppression (Rasgon et al, 2005).

Now a days, approximately 26 billion animals, spanning over 10 000 species, are kept on farms and in zoos, conservation breeding centers, research laboratories and households (Manson, 2010). Taking into account that captivity is a well-known acute stressor (Gregory et al, 1996), if proper conditions of the habitat are not reestablished or defined, acute stress may turn into chronic stress, and consequently lead to problems that are particularly undesirable for animals maintained in captivity; including increased abnormal behavior, increased self-injurious behavior, impaired reproduction and immunosuppression (Morgan et al, 2007). Besides, it’s been demonstrated that stressful conditions on cattle elicit changes in muscle gross morphology in direct proportion with the duration of the stressor, thus a negative effect on the meat quality and other products for human consumption (Judge, 1969).

Likewise, human beings are prone to stressful conditions; Constant exposure to adverse environments like noise and pollution or other lifestyle and social conflicts may cause chronic stress that result, over time, in pathophysiological conditions like atherosclerosis, which can lead to strokes and myocardial infarctions (McEwen, 2007).

Identifying a standardized mechanism that allows an early detection of stress is of high importance in different applications such as animal conservation and human practices such as investigation, medicine, animal breeding and cattle raising. Also, doing the proper characterization of the different types of stress provide insight information about the animal condition and therefore, assist an early diagnosis to prevent acute stress to become chronic.

Nowadays, hormones act as biological markers of stress; In this practices the so called “stress-hormones” such as cortisol in humans and corticosterone in rats are quantified to provide information of stress in animals; Elisa, which is the gold standard for stress determination is highly precise and specific; nevertheless this and most methods that utilize immunoassays are only available for lab practices and involve the manipulation of difficult machinery and specialized procedures that are not available for daily use and which are difficult and expensive to implement in farms, home or other in situ investigations.

We propose a standardized device that’ll detect stress with no need of complex machinery or procedures, but a versatile and easy to use device that can be used by anyone, from a farmer in livestock practices, to yourself at home, to identify if your own pet is held in good conditions and stress-free. The device will sense the presence of one of the “stress hormones”, depending on the specimen used, and compare it to a normal concentration or base line. If the concentration of the hormone sensed is more than usual, the device will send a visual signal to inform the user of the presence of stress. The sensing will be done by a bio-machinery held inside the genetic code of saccharomyces cerevisae. Thus, our genetically manufactured yeast will identify if there’s abnormal presence of the hormone and if the threshold established is reached, elicit the alarm signal using m-cherry.

This project that is aimed to a larger population than the methods previously released, can be used for both formal and informal characterization of stress. In previous examination with members of the laboratory of neuroscience of Andes University, they did recognize the asset of the device to objectively characterize behavior with fewer limitations and costs than with ELISA kit. Besides, interviews with veterinarians provide evidence that the animals held in households and other facilities such as animal breeding centers and farms, often require close observation to avoid negative effects associated with stressed animals.

Although we did recognize that identifying stress in animals is of high important in different fields, we propose to initialize the project with trials on humans mostly because of the vast amount of information on the circadian rhythms and baselines of cortisol (read more here), the main “stress hormone” in humans. Nevertheless, we intent to create a product with different final users, based on personalized needs. This requires a bigger effort as baselines for each specimen shall be established in order to identify the “all or nothing” threshold.

Besides, we propose as future prospects, the possibility to implement various baselines in order to provide a more quantitatively response to the presence of stress, rather than the off-on system originally proposed.

Design: Project Parts!

Glucocorticoid sensor

Our construct

We plan to use the baker's yeast, ''Saccharomyces cerevisiae'', as a chassis for a plasmid which will contain a chimeric protein used as a transactivating factor in a biosensor with a colored reporter.

The Chassis

We chose ''S. cerevisiae'' as the chassis because one of the most important parts of our fusion protein, the glucocorticoid receptor hormone binding domain (GCR HBD) is eukaryotic, therefore we wanted an easy to use, easy to grow, eucaryotic vector to express our protein and build our biosensor.

The Chimera

The glucocorticoid receptor (GCR) from mammals contains three domains necessary for stress hormone related gene transcription, the hormone binding domain (HBD), the DNA binding domain (DNA-BD) and the gene transactivating domain (GTD).

However, for our construct's performance we used a chimeric protein. Just as the mythological creature made from fused parts from a lion, a goat and a snake, we created a chimeric protein using three domains from different organisms.

We used the glucocorticoid receptor hormone binding domain (GCR HBD) which came from a rat to recognize our hormones of interest. However, we replaced the other two domains with the herpesvirus gene transactivating domain (HV-GTD) and the yeast's DNA binding domain from GAL4. These two new domains have the advantage of being already used, characterized and being highly efficient. The HV-GTD is a highly efficient transactivating domain, recognized to be several orders of magnitude better than the GCR-GTD.

Tester Construct

References:

- Greenberg, N., and Wingfield, J. C. (1987). Stress and reproduction: Reciprocal relationships. In ‘‘Hormones and Reproduction in Fishes, Amphibians and Reptiles’’ (D. O. Norris and R. E. Jones, Eds.), pp. 461–503. Plenum, New York.

- Gregory, Lisa. Gross, Timothy. Bolten, Alan. Bjorndal, Karen. Guillette, Louis. (1996) Plasma Corticosterone Concentrations Associated with Acute Captivity Stress in Wild Loggerhead Sea Turtles (Caretta caretta). General and Comparative Endocrinology 104, 312–320

- Judge, M.D. (1969) Environmental Stress and Meat Quality. Journal of Animal Science, 28: 755-760.

- Kirschbaum C, Prussner JC, Stone AA, Federenko I, Gaab J, Lintz D, Schommer N, Hellhammer DH. (1995) Persistent high cortisol responses to repeated psychological stress in a subpopulation of healthy men. Psychosomatic Med 57: 468–474.

- Manson, Georgia J. (2010) Species differences in responses to captivity: stress, welfare and the comparative method. Trends in Ecology and Evolution. Volume 25, Issue 12: Pages 713–721

- McEwen, Bruce S. (2007) Physiology and Neurobiology of Stress and Adaptation: Central Role of the Brain. Physiol Rev 87: 873–904

- McEwen BS, Chattarji S. (2004) Molecular mechanisms of neuroplasticity and pharmacological implications: the example of tianeptine. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 14: 497–502.

- Morgan, Kathleen. Tromborg, Chris. (2007) Sources of stress in captivity. Applied Animal Behaviour Science. Volume 102: 262–302

- Mirescu C, Gould E. (2006) Stress and adult neurogenesis. Hippocampus16: 233–238

- Rasgon NL, Kenna HA. (2005) Insulin resistance in depressive disorders and Alzheimer’s disease: revisiting the missing link hypothesis. Neurobiol Aging 26S: S103–S107

- Sachar EJ, Hellman L, Roffwarg HP, Halpern FS, Fukushima DK, Gallagher TF. (1973)Disrupted 24-hour patterns of cortis8ol secretion in psychotic depression. Arch Gen Psychiarty 28: 19–24

- Stephens, D. B. (1980). Stress and its measurement in domestic animals: A review of behavioral and physiological studies under field and laboratory conditions. Adv. Vet Sci. Comp. Med. 24, 179–210.

"

"