Team:Bielefeld-Germany/Project/Riboflavine

From 2013.igem.org

Riboflavine

Overview

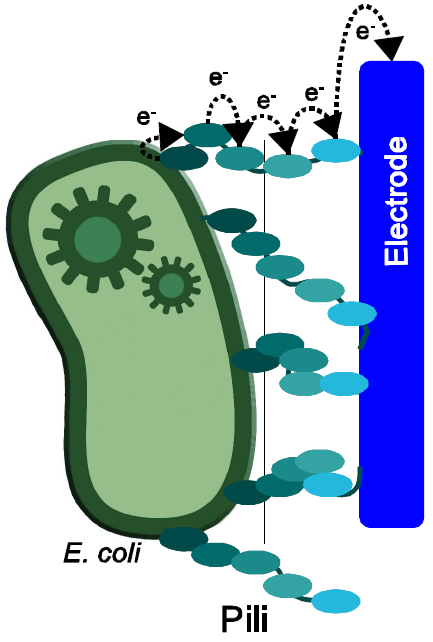

Multiple bacteria form special, highly conductive pili, which are required for survival in anaerobe environment. Electrons, which are generated through the oxidation of different substrates, can be transported by these pili and transferred to alternative electron-acceptors, such as sulfur or iron. These so called nanowires could furthermore increase the number of bacteria contacting the surface of the anode. These properties make them another interesting option, regarding the optimization of E. coli for the use in MFCs. Because several large gene clusters are required to form nanowires in organisms such as Geobacter sulfurreducens, it will be first investigated, whether the existing type 4 pili are suitable for electron conduction by E. coli as well.

Theory

Since its discovery in 1879 and its first structural characterization in 1930th (in the 1930’s/in 1930), a lot of properties of riboflavin were elucidated. This substance is a precursor of FMN (flavin mononucleotide) and FAD (flavin adenine dinucleotide), which play an essential role as cofactors in many oxidative processes. The modern name Riboflavin, also named Lactoflavin, is composed of two parts: «ribo» indicating the presence of the sugar alcohol ribitol, and «flavin» meaning «yellow»; to accentuate the yellow coloring of the oxidized molecule. Chemically this substance consists of two functional subunits, an already mentioned short-chain ribitol and a tricyclic heterosubstituted isoalloxazine ring. The latter, also known as a riboflavin ring, exists in three redox states and is responsible for the diverse chemical activity of riboflavin. A fully oxidized quinone, a one-electron semiquinone and a fully reduced hydroquinone states are the three stages of riboflavin oxidation. In an aqueous solution, the quinone (fully oxidized) form of riboflavin has a typical yellow coloring. It becomes red in a semi-reduced anionic or blue in a neutral form and is colorless when fully reduced.

All these forms are present in different proportions in a living cell, making previous oxidation a necessary step if riboflavin analysis is to be conducted. Flavins have a typical yellow-green fluorescence in the UV light. The peaks of absorbance occur at 223, 266, 373 and 445 nm. The maximum fluorescence emission of the neutral solution is at 535 nm [Charles A. Abbas et al.,[http://mmbr.asm.org/content/75/2/321.full#ref-292| 2011]]. These fluorimetric properties are widely used in the analysis of riboflavin. Due to its structure, which allows a transfer of two electrons from hydrogen and hydrid ions, riboflavin can be imagined as a potential electron shuttle. It was previously known, that the electron transfer from the outer membrane-associated proteins to an inorganic electron acceptor is the main limiting growth factor for Fe(III)-reducing prokaryotes, so a few mechanisms were discovered, which showed how this process can be enhanced. One of them was a secretion of water-soluble redox mediators. It was proven, that secretion of riboflavin and FMN enhances the rate of insoluble mineral oxides reduction. Indeed, Shewanella Oneidensis, a facultative Fe-III respiring bacterium uses secreted riboflavin as its electron transmitter [Harald von Canstein et al.,[http://aem.asm.org/content/74/3/615.full| 2008]]. Considering this acknowledgement, we decided to overproduce riboflavin in E.Coli to improve its efficiency in our MFC.

Genetic Approach

First of all, we have searched for a suitable microorganism, which has an active riboflavin cluster with known coding sequences. We have already used the remarkable versatility of Shewanella in order to clone the anaerobic respiratory chain (mtrCAB cluster), so now we were able to skip some initial steps, like the whole genome DNA isolation and advanced rapidly to more specific steps. Before planning the cloning strategy, we checked [http://parts.igem.org/Main_Page| the Parts registry] for any parts we could use or enhance. A [http://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K769203| ribC part] was listed, but it was neither submitted nor available. We also had a close look on the [http://www.chem.qmul.ac.uk/iubmb/enzyme/reaction/misc/riboflavin2.html|riboflavin biosynthesis pathway]. This process is well studied and a lot of appropriate literature is available. There are three types of riboflavin overproducers used in industry: yeast (Candida famate), fungi (Ashbya gossypii), and bacteria (Bacillus subtilis) [Overview, Seong Han Lim et al., [http://www.bbe.or.kr/storage/journal/BBE/6_2/6657/articlefile/article.pdf| 2001]], but a prevailing majority of microorganisms also synthesise riboflavins in low concentrations. In E.Coli, for instance, genes are scattered through the whole genome and riboflavin is produced constitutively. The biosynthesis of riboflavin starts with ribulose-5-phosphate and GTP, converted to formate and DHBP (L-3,4-dihydroxybutan-2-one 4-phosphate). The final stage involves forming of the third isoalloxazine ring by an exchange of a 4-carbon part, catalysed by riboflavin synthetase (EC 2.5.1.9). We assumed, that the operon in Shewanella could be similar to a well-studied [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8159171| rib-operon] of Bacillus Subtilis. The operon is transcribed as a one polycistronic RNA, making a single promoter sufficient. Introduction of multiple copies of a ribA gene (coding for GTP cyclohydrolase II (EC 3.5.4.25)), comprised in the rib-operon, results in riboflavin overproduction in B.Subtilis [Hohmann H.P.,Stahmann K.P. 2010. Biotechnology of riboflavin production, p. 115–139.], so we predicted a notable riboflavin synthesis gain following a successful introduction of a multiple-copy plasmid harbouring the rib-operon under an active promoter.

Results

References

</div>

"

"