Team:Heidelberg/Project/Delftibactin

From 2013.igem.org

| (94 intermediate revisions not shown) | |||

| Line 12: | Line 12: | ||

p { | p { | ||

text-align:justify; | text-align:justify; | ||

| + | } | ||

| + | .col-sm-12 h2, | ||

| + | .col-sm-6 h2 { | ||

| + | font-size:220%; | ||

| + | } | ||

| + | .wikitable th, .wikitable tr { | ||

| + | font-size:14px; | ||

} | } | ||

</style> | </style> | ||

| Line 26: | Line 33: | ||

<a class="fancybox fancyGraphical" href="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/e/e3/Heidelberg_ga_delf.png" rel="group"><img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/e/e3/Heidelberg_ga_delf.png" style="width:100%; margin-bottom:10px; padding:1%;border-style:solid;border-width:1px;border-radius: 4px; border-color: grey;" /></a> | <a class="fancybox fancyGraphical" href="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/e/e3/Heidelberg_ga_delf.png" rel="group"><img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/e/e3/Heidelberg_ga_delf.png" style="width:100%; margin-bottom:10px; padding:1%;border-style:solid;border-width:1px;border-radius: 4px; border-color: grey;" /></a> | ||

<div class="jumbotron"> | <div class="jumbotron"> | ||

| - | + | <b> <h2>Highlights</h2> | |

<p style="font-size:16px"> | <p style="font-size:16px"> | ||

<ul style="font-size:14px"> | <ul style="font-size:14px"> | ||

| Line 33: | Line 40: | ||

<li> Optimization of the Gibson assembly method for the creation of large plasmids (> 30 kbp) with high GC content. | <li> Optimization of the Gibson assembly method for the creation of large plasmids (> 30 kbp) with high GC content. | ||

<li> Amplification and cloning of all components required for recombinant delftibactin production. | <li> Amplification and cloning of all components required for recombinant delftibactin production. | ||

| - | <li> Transfer of the entire pathway from <i> | + | <li> Transfer of the entire pathway from <i>Delftia acidovorans</i> for the synthesis of delftibactin to <i>Escherichia coli</i>. |

</ul> | </ul> | ||

| - | </p> | + | </p> </b> |

</div> | </div> | ||

| Line 93: | Line 100: | ||

<div class="col-sm-6"> | <div class="col-sm-6"> | ||

| - | <div class="jumbotron abstract" style="height: | + | <div class="jumbotron abstract" style="height:1040px"> |

<h2>Abstract</h2> | <h2>Abstract</h2> | ||

<p style="font-size:14px; text-align:justify"> | <p style="font-size:14px; text-align:justify"> | ||

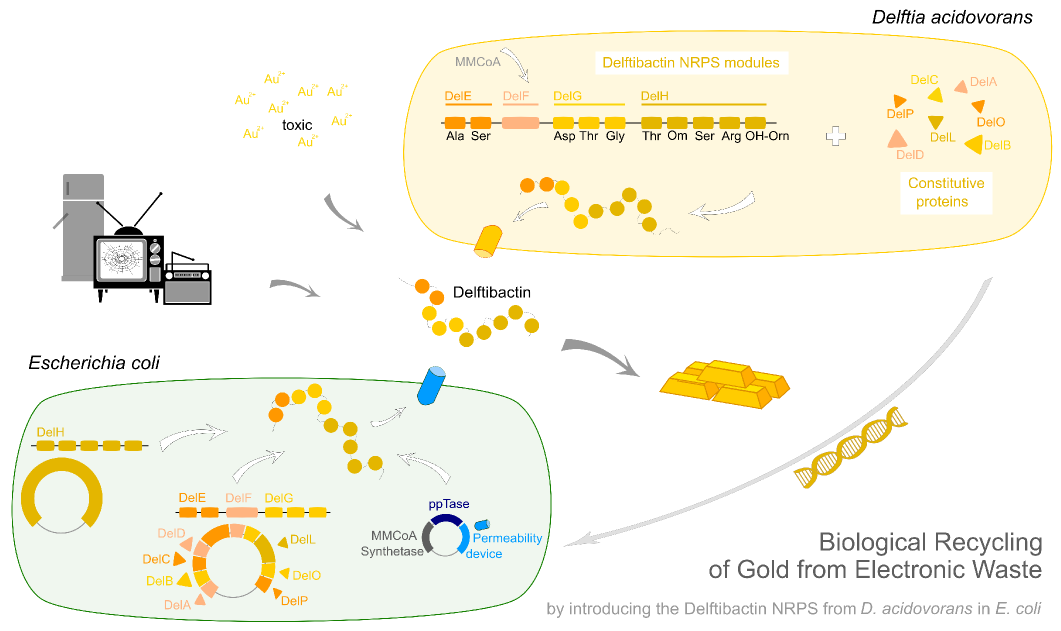

| - | + | Undoubtedly, <b>gold</b> is one of the most precious materials on earth. Besides its common use in art and jewelry, gold is also an essential component of our modern computers and cell-phones. Due to the fast turn-over of today’s high-tech equipment, millions of tons of <b>electronic waste</b> accumulate each year containing tons of this valuable metal. The main approach nowadays to recycle gold from electronic waste is by electrolysis. Unfortunately, this is a highly inefficient and expensive procedure, preventing most of the gold from being recovered.<br/><br/> | |

| - | + | In this subproject we want to demonstrate that the gold-precipitating natural secondary metabolite <b>delftibactin</b>, a non-ribosomal peptide produced by the bacterium <i>Delftia acidovorans</i>, can be used for the <b>efficient recovery of gold</b> from electronic waste.<br/><br/> | |

| - | + | Moreover we want to show that very large constructs such as the genes needed for the production of delftibactin which are encoded on a 59 kbp long gene cluster can be succesfully inserted into <i>Escherichia coli</i>. Furthermore the aim is to <b>recombinantly express</b> the responsible <b>NRPSs</b> with the promising perspective that delftibactin could readily be produced and used as an efficient way of gold recycling from electronic waste.<br/><br/> | |

| - | + | We managed to introduce and express the genes needed for delftibactin production. Furthermore the <b>recycling of gold from electronic waste</b> with delftibactin was <b>successful</b>. Consequently the industrial usage of recombinantly expressed delftibactin as an efficient method to recover gold becomes conceivable. <br/><br/> | |

| - | |||

</p> | </p> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

| Line 114: | Line 120: | ||

<div id="delftibactinText" class="col-sm-12"> | <div id="delftibactinText" class="col-sm-12"> | ||

<h2 id="introduction">Introduction</h2> | <h2 id="introduction">Introduction</h2> | ||

| - | <p>The quest for a magical substance to generate gold from inferior metals stirred the imagination of generations. However, this substance, the Philosopher’s Stone, stands for more than just the desire to produce gold. | + | <p>The quest for a magical substance to generate gold from inferior metals stirred the imagination of generations. However, this substance, the Philosopher’s Stone, stands for more than just the desire to produce gold. There was a time when the fabled Philosopher’s Stone also represented wisdom, rejuvenation and health. Nowadays, gold is still of great importance for us as it is needed for most of our electronic devices.</p> |

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | < | + | <p>In 2007, more than two tons of gold, worth $92 million, were discarded hidden in electronic waste in Germany [1]. Most of the precious element ends up on waste disposal sites as only a minor fraction of 10-15% [2] of the gold is recycled also due to the small amounts per device. Since our planet’s gold supplies are limited, the metal is more and more depleted and the value of gold continuously reaches all-time highs. In order to satisfy our society’s need for gold, we have to develop heavy mining techniques involving strong acids, causing devastating impact on humans and environment [3] [4] [5].</p> |

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | <p>Besides economical usage of the resource <i>gold</i>, one way to reduce global demands for gold is elevation of gold recovery [6]. Intriguingly, nature itself offers a structure that has been reported to efficiently extract pure gold from solutions containing gold ions. This fascinating molecule is called delftibactin and is in fact a small peptide secreted by a gold-ion-tolerant bacterium called <i>Delftia acidovorans</i> [7].</p> | |

| - | + | ||

| - | </ | + | |

| - | </ | + | |

| - | + | ||

| + | <p>This extremophile has the incredible ability to withstand toxic amounts of gold ions in contaminated soil. If one could culture these bacteria and produce delftibactin in large scales, could one potentially recover gold from electronic waste in a cost- and energy-efficient way? But what is the special feature of delfibactin to precipitate gold that efficiently?</p> | ||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | <p>Delftibactin is a NRP produced by a hybrid NRPS/ polyketide synthase (PKS) system. In their recent publication, Johnston | + | <p>Delftibactin is a non-ribosomal peptide (NRP) [7] [8]. The efficient and non-pollutant large-scale production of this NRP in <i>Escherichia coli</i> could revolutionize the recovery of gold from electronic waste and additionally highlight the plethora of versatile applications for non-ribosomal peptide synthetases (NRPSs). The most striking feature of these non-ribosomal synthetases is their ability to incorporate far more than the 21 common amino acids into peptides. They make use of numerous modified and even non-proteinogenic amino acids to assemble peptides of diverse functions [9].</p> |

| + | |||

| + | <p>Delftibactin is a NRP produced by a hybrid NRPS/polyketide synthase (PKS) system. In their recent publication, Johnston and colleagues [7] predicted that the enzymes responsible for producing delftibactin are encoded on a single gene cluster, hereafter referred to as del cluster | ||

| + | |||

| + | (<a class="fancybox fancyFigure" title="Cluster of genes responsible for Delftibactin production. The cluster consists of the genes Daci_4754 to Daci_4765. The proteins DelE, DelF, DelG and DelH are directly responsible for the production of delftibactin. Domain architecture of the NRPS-PKS hybrid assembly-line is shown which consists of adenylation (A), thiolation (T), condensation, (C), ketosynthase (KS), acyltransferase (AT), ketoreductase (KR) and thioesterase domains. The predicted structure of delftibactin is shown below." href="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/9/96/Heidelberg_Del_Cluster.png" rel="gallery1">Fig. 1</a>). | ||

| + | |||

| + | It comprises 59 kbp encoding for 21 genes. DelE, DelF, DelG and DelH constitute the hybrid NRPS/ PKS system producing delftibactin, with DelE, DelG and DelH comprising the NRPS and DelF the PKS. The remaining enzymes involved in the delftibactin synthesis pathway are required for maturation or post-synthesis modification of delftibactin. The predicted activities [7] of the proteins are:</p> | ||

<p> | <p> | ||

<ol style="list-style-type: decimal"> | <ol style="list-style-type: decimal"> | ||

| - | <li>DelA: MbtH-like protein, most likely required for efficient delftibactin synthesis <span class="citation">[ | + | <li>DelA: MbtH-like protein, most likely required for efficient delftibactin synthesis <span class="citation">[10]</span></li> |

<li>DelB: thioesterase</li> | <li>DelB: thioesterase</li> | ||

<li>DelC: 4’-phosphopanteinyl transferase: required for maturation of ACP/PCP subunits</li> | <li>DelC: 4’-phosphopanteinyl transferase: required for maturation of ACP/PCP subunits</li> | ||

| Line 152: | Line 147: | ||

</ol> | </ol> | ||

</p> | </p> | ||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

<br/> | <br/> | ||

<center> | <center> | ||

| - | <a class="fancybox fancyGraphical" href="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/ | + | <a class="fancybox fancyGraphical" href="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/9/96/Heidelberg_Del_Cluster.png" title="Cluster of genes responsible for Delftibactin production. The cluster consists of the genes Daci_4754 to Daci_4765. The proteins DelE, DelF, DelG and DelH are directly responsible for the production of delftibactin. Domain architecture of the NRPS-PKS hybrid assembly-line is shown which consists of adenylation (A), thiolation (T), condensation, (C), ketosynthase (KS), acyltransferase (AT), ketoreductase (KR) and thioesterase domains. The predicted structure of delftibactin is shown below."> |

| - | <img style="width: | + | <img style="width:60%; margin-bottom:10px; padding:1%;border-style:solid;border-width:1px;border-radius: 5px;" src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/9/96/Heidelberg_Del_Cluster.png"> |

| - | <figcaption style="width:60%;"><b> | + | <figcaption style="width:60%;"><b>Figure 1: Cluster of genes responsible for Delftibactin production.</b> The cluster consists of the genes Daci_4754 to Daci_4765. The proteins DelE, DelF, DelG and DelH are directly responsible for the production of delftibactin. Domain architecture of the NRPS-PKS hybrid assembly-line is shown which consists of adenylation (A), thiolation (T), condensation, (C), ketosynthase (KS), acyltransferase (AT), ketoreductase (KR) and thioesterase domains. The predicted structure of delftibactin is shown below. Figure adopted from <span class="citation">[7]</span>.</figcaption> |

</a> | </a> | ||

</center> | </center> | ||

| - | <br> | + | <br/> |

| - | < | + | <p>We introduced the large del cluster into the commonly used, easy-to-culture model organism <i>E. coli</i> with the aim of recombinant delftibactin expression. Although the del cluster contains the native PPTase of <i>D. acidovorans</i> we additionally introduced the sfp phosphopanteinyl transferase from <i>Bacillus subtilis</i> as this PPTase is able to activate a wide variety of PKSs including those from <i>Saccharomyces cerevisiae</i>. Importantly, it has been proven to work in <i>E. coli</i> by the <a href='https://2013.igem.org/Team:Heidelberg/Project/Tag-Optimization'>indigoidine project</a> of our own team [11]. Additionally, DelF, the polyketide synthetase of the del cluster requires methylmalonyl-CoA as substrate. This metabolite, from now on abbreviated as mmCoA is not produced by <i>E. coli</i>. Therefore, we also transfer the mmCoA synthesis pathway from <i>B. subtilis</i> into <i>E. coli</i>. This should allow for efficient production of recombinant delftibactin.</p> |

| - | < | + | |

| - | < | + | <p>As the del cluster starts with Daci_4760 (DelA; Daci IDs are NCBI Gene gene symbols, Del* gene names as referred to in [12]) and promoters within the Del-cluster were bioinformatically predicted upstream of Daci_4750 (DelK), Daci_4760 (DelA) and Daci_4746 (DelO) we assumed that the entire sequence from Daci_4760 (DelA) to Daci_4753 (DelH) is transcribed as a single polycistronic mRNA of approximately 40 kbp in size [12].</p> |

| - | < | + | |

| - | < | + | <p>Facing these challenges, we decided to approach the project by cultivation of <i>D. acidovorans</i> and the isolation of native delftibactin to reproduce the findings of Johnston and colleagues [7].</span></p>. |

| - | < | + | |

| - | <li>< | + | <p>In order to achieve recombinant expression of delftibactin, we decided to introduce constructs coding for the delftibactin-cluster the methylmalonyl-CoA pathway and the PPTase sfp. In addition, we transformed the permeability device <a href='http://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_I746200'>BBa_I746200</a> from the parts registry for the export of recombinant delftibactin out of the target organism <i>E. coli</i>. The desired genes from the del cluster were subdivided onto two different plasmids in order to decrease plasmid size and thereby avoid the intricacies expected for cloning of a single 59 kbp plasmid as well as to allow for faster trouble shooting in case issues with the cloning of particular genes occur:</p> |

| + | |||

| + | <ol> | ||

| + | <li>Plasmid: methylmalonyl-CoA pathway, PPTase sfp & permeability device <a href='http://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_I746200'>BBa_I746200</a>, transcription regulated by inducible lac promoter, chloramphenicol resistance;</li> | ||

| + | <li>Plasmid: DelH, transcription regulated by inducible lac promoter, ampicillin resistance;</li> | ||

| + | <li>Plasmid: DelA-P, genes of the del cluster required for production of delftibactin, transcription regulated by inducible lac promoter, kanamycin resistance.</li> | ||

</ol> | </ol> | ||

| - | <p> | + | |

| + | <p>Here we show successful amplification, cloning and transformation of plasmids above 30 kbp in size as well as expression of the desired genes of the del cluster from its natural host <i>D. acidovorans</i>. Furthermore, we demonstrate efficient recovery of purified gold from electronic waste using the non-ribosomal peptide delftibactin. Additionally, we proved toxicity of DelH for our target organism <i>E. coli</i> when expressed as the only gene of the del cluster: cloning of DelH into a construct without promoter lead to depletion of DelH from our target system which previously had been selecting for mutated versions of DelH.</p> | ||

| + | |||

<h2>Results</h2> | <h2>Results</h2> | ||

| - | <h3>Efficient Recycling of Gold from Electronic Waste | + | <h3>Efficient Recycling of Gold from Electronic Waste Using Endogenously-Derived Delftibactin</h3> |

| + | |||

| + | <p>As a first step into the direction of an environmentally friendly procedure for recycling gold from gold-containing waste, we wanted to show that the non-ribosomal peptide delftibactin can be used to precipitate gold from gold ion-containing solutions.</p> | ||

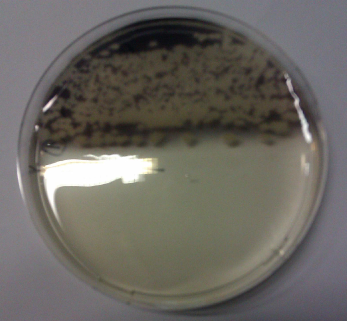

| - | <p> | + | <p>We obtained <i>D. acidovorans</i> DSM-39 from the DSMZ and successfully reproduced the paper by Johnston and colleagues [7]. What they had been able to show was that delftibactin selectively precipitates gold from gold solution. In our experiments, precipitation on agar plates worked even better than described by Johnston <em>et al.</em> |

| - | < | + | (<a class="fancybox fancyFigure" title="ACM agar plate with D. acidovorans DSM-39 overlaid with 0.2% HAuCl4 in 0.5% agarose. <i>D. acidovorans</i> had only been growing on the upper part of the shown plate. One can clearly see that gold nanoparticles are exclusively formed on the part of the plate harboring bacteria." href="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/6/66/Heidelberg_IMAG0449.png" rel="gallery1">Fig. 2</a>). |

| + | <i>D. acidovorans</i> is capable to precipitate solid gold from gold chloride solution as purple-black nanoparticles.</p> | ||

<br/> | <br/> | ||

<center> | <center> | ||

| - | <a class="fancybox fancyGraphical" href="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/6/66/Heidelberg_IMAG0449.png" title="ACM agar plate with D. acidovorans | + | <a class="fancybox fancyGraphical" href="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/6/66/Heidelberg_IMAG0449.png" title="Figure 2: <i>D. acidovorans</i> precipitates elementary gold from gold solution.</b> ACM agar plate with <i>D. acidovorans</i> DSM-39 overlaid with 0.2% HAuCl<sub>4</sub> in 0.5% agarose. <i>D. acidovorans</i> had only been growing on the upper part of the shown plate. One can clearly see that gold nanoparticles are exclusively formed on the part of the plate harboring bacteria."> |

| - | <img style="width:30%; margin-bottom:10px; padding:1%;border-style:solid;border-width:1px;border-radius: 5px;" src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/6/66/Heidelberg_IMAG0449.png" | + | <img style="width:30%; margin-bottom:10px; padding:1%;border-style:solid;border-width:1px;border-radius: 5px;" src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/6/66/Heidelberg_IMAG0449.png"> |

| - | <figcaption style="width:60%;"><b> | + | <figcaption style="width:60%;"><b>Figure 2: <i>D. acidovorans</i> precipitates elementary gold from gold solution.</b> ACM agar plate with <i>D. acidovorans</i> DSM-39 overlaid with 0.2% HAuCl<sub>4</sub> in 0.5% agarose. <i>D. acidovorans</i> had only been growing on the upper part of the shown plate.One can clearly see that gold nanoparticles are exclusively formed on the part of the plate harboring bacteria. </figcaption> |

</a> | </a> | ||

</center> | </center> | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

| - | <p style="clear:both"> | + | <p style="clear:both">We also showed that another strain, <i>D. acidovorans</i> SPH-1, is also able to precipitate gold ions to gold nanoparticles. When using the supernatant of a culture gold nanoparticles were precipitated at an amount which caused a color change to black already at low concentrations of 0.35 µg/ml of gold chloride. With increasing concentration of gold chloride more nanoparticles formed, even though the process became slower above a certain concentration (Video 1 and |

| + | |||

| + | <a class="fancybox fancyFigure" title="Supernatant of <i>D. acidovorans</i> culture is sufficient for gold precipitation. a) Sequences of movie over time showing gold precipitation in D. acidovorans supernatant using different concentrations of HAuCl<sub>4</sub>. From left to right: 0 µg/ml, 0.15 µg/ml, 0.35 µg/ml, 0.55 µg/ml, 0.75 µg/ml, 0.95 µg/ml, 1.15 µg/ml, 1.35 µg/ml, 1.55 µg/ml, 1.75 µg/ml, 1.95 µg/ml, 2.15 µg/ml, 2.35 µg/ml and 2.55 µg/ml. b) Sparkling gold appearing in the melting pot after the precipitation of gold ions using the supernatant of <i>D. acidovorans</i> SPH-1. c) Final recovered solid gold with Delftibactin collected in tube. d) Solid gold covering the walls of a 2 ml tube after the application of delftibactin to gold solution." href="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/8/8e/Zusammenstellung1.png" rel="gallery1">Fig. 3a</a>). An optimum is visible at a concentration of about 1.15 µl/ml of gold solution. Johnston <i>et al.</i> [7] described that the optimal ratio of gold ions to delftibactin is 1:1. Therefore it can be concluded that 1.96 nmol of delftibactin was present in 1 ml of <i>D. acidovorans</i> supernatant. | ||

| + | Furthermore, we melted the purple-black nanoparticles to shiny, solid gold as shown in | ||

| + | <a class="fancybox fancyFigure" title="Testing the precipitation gold with <i>D. acidovorans</i> supernatant. a) Sequences of movie over time showing gold precipitation in D. acidovorans supernatant using different concentrations of AuCl4. From left to right: 0 µg/ml, 0.15 µg/ml, 0.35 µg/ml, 0.55 µg/ml, 0.75 µg/ml, 0.95 µg/ml, 1.15 µg/ml, 1.35 µg/ml, 1.55 µg/ml, 1.75 µg/ml, 1.95 µg/ml, 2.15 µg/ml, 2.35 µg/ml and 2.55 µg/ml. b) Sparkling gold appearing in the melting pot after the precipitation of gold ions using the supernatant of <i>D. acidovorans</i> SPH-1. c) Final recovered solid gold with Delftibactin collected in tube. d) Solid gold covering the walls of a 2 ml tube after the application of delftibactin to gold solution." href="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/8/8e/Zusammenstellung1.png" rel="gallery1">Fig. 3b,c,d</a>.</p> | ||

<br/> | <br/> | ||

<center> | <center> | ||

| - | <a class="fancybox fancyGraphical" href="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/8/8e/Zusammenstellung1.png" title=" | + | <div> |

| - | <img style="width:50%; margin-bottom:10px; padding:1%;border-style:solid;border-width:1px;border-radius: 5px;" src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/8/8e/Zusammenstellung1.png" | + | <iframe id="video" width="480" height="360" src="//www.youtube.com/embed/xsB9_7Acuyk" frameborder="0" allowfullscreen></iframe> |

| - | <figcaption style="width:60%;"><b> | + | <p style="margin-left:20%; margin-right:20%; margin-top:5px"><b>Video 1: Precipitation of elementary gold by delftibactin is dependent on the ratio of peptide to gold ions</b>. Different concentrations of gold solution applied to the supernatant of a <i>D. acidovorans</i> SPH-1 culture. From left to right: 0 µg/ml, 0.15 µg/ml, 0.35 µg/ml, 0.55 µg/ml, 0.75 µg/ml, 0.95 µg/ml, 1.15 µg/ml, 1.35 µg/ml, 1.55 µg/ml, 1.75 µg/ml, 1.95 µg/ml, 2.15 µg/ml, 2.35 µg/ml and 2.55 µg/ml HAuCl<sub>4</sub>. Black gold nanoparticles form due to the precipitation of solid gold from solution by the NRP delftibactin. According to Johnston and colleages, gold precipitation is most sufficient at peptide to gold ions ration of 1:1 [7], suggesting an amount of peptide of 1.96 nmol. The process is shown in time-lapse and had an actual duration of 8min 23s.</p> |

| + | </div> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <a class="fancybox fancyGraphical" href="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/8/8e/Zusammenstellung1.png" title="Supernatant of <i>D. acidovorans</i> culture is sufficient for gold precipitation. a) Sequences of movie over time showing gold precipitation in <i>D. acidovorans</i> supernatant using different concentrations of AuCl4. From left to right: 0 µg/ml, 0.15 µg/ml, 0.35 µg/ml, 0.55 µg/ml, 0.75 µg/ml, 0.95 µg/ml, 1.15 µg/ml, 1.35 µg/ml, 1.55 µg/ml, 1.75 µg/ml, 1.95 µg/ml, 2.15 µg/ml, 2.35 µg/ml and 2.55 µg/ml. b) Sparkling gold appearing in the melting pot after the precipitation of gold ions using the supernatant of <i>D. acidovorans</i> SPH-1. c) Final recovered solid gold with Delftibactin collected in tube. d) Solid gold covering the walls of a 2 ml tube after the application of delftibactin to gold solution."> | ||

| + | <img style="width:50%; margin-bottom:10px;margin-top:5%; padding:1%;border-style:solid;border-width:1px;border-radius: 5px;" src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/8/8e/Zusammenstellung1.png"> | ||

| + | <figcaption style="width:60%;"><b>Figure 3: Supernatant of <i>D. acidovorans</i> culture is sufficient for gold precipitation. </b> a) Sequences of movie over time showing gold precipitation in <i>D. acidovorans</i> supernatant using different concentrations of HAuCl<sub>4</sub>. From left to right: 0 µg/ml, 0.15 µg/ml, 0.35 µg/ml, 0.55 µg/ml, 0.75 µg/ml, 0.95 µg/ml, 1.15 µg/ml, 1.35 µg/ml, 1.55 µg/ml, 1.75 µg/ml, 1.95 µg/ml, 2.15 µg/ml, 2.35 µg/ml and 2.55 µg/ml. b) Sparkling gold appearing in the melting pot after the precipitation of gold ions using the supernatant of <i>D. acidovorans</i> SPH-1. c) Final recovered solid gold with Delftibactin collected in tube. d) Solid gold covering the walls of a 2 ml tube after the application of delftibactin to gold solution.</figcaption> | ||

</a> | </a> | ||

</center> | </center> | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

| - | <p style="clear:both">Next, we established purification | + | <p style="clear:both">Next, we established a purification protocol for delftibactin using HP20 resins. Additionally, we proved precipitation of gold by the purified delftibactin |

| + | (<a class="fancybox fancyFigure" title="Purified Delftibactin precipitates gold from gold solution. From left to right: ddH2O, 1:10 ACM media in water, 1:10 supernatant of D. acidovorans SPH-1 in water, 1:10 filtered supernatant of D. acidovorans SPH-1 in water, 1:10 purified delftibactin in water; gold solution: 0.6 µg/ml HAuCl<sub>4</sub>." href="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/1/12/Heidelberg_IMG_4368.JPG" rel="gallery1">Fig. 4</a>) | ||

| + | and detected it by Micro-TOF | ||

| + | (<a class="fancybox fancyFigure" title="Micro-TOF results for ACM media (top) compared to purified supernatant of a <i>D. acidovorans</i> SPH-1 liquid culture (middle). Delftibactin is present in <i>D. acidovorans</i>SPH-1 supernatant but not in the pure ACM-media as can be seen from the peak at about 1055.5, 1033.5, 517.2 and 539.2 shown in the enlargements (bottom)." href="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/1/11/Heidelberg_Microtof-Delftia.png" rel="gallery1">Fig. 5</a>).</p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| - | |||

<center> | <center> | ||

| - | <a class="fancybox fancyGraphical" href="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/1/ | + | <a class="fancybox fancyGraphical" href="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/1/12/Heidelberg_IMG_4368.JPG" title="Purified Delftibactin precipitates gold from gold solution. From left to right: ddH2O, 1:10 ACM media in water, 1:10 supernatant of D. acidovorans SPH-1 in water, 1:10 filtered supernatant of D. acidovorans SPH-1 in water, 1:10 purified delftibactin in water; gold solution: 0.6 µg/ml HAuCl<sub>4</sub>."> |

| - | <img style="width: | + | <img style="width:40%; margin-bottom:10px; padding:1%;border-style:solid;border-width:1px;border-radius: 5px;" src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/1/12/Heidelberg_IMG_4368.JPG"> |

| - | <figcaption style="width:60%;"><b> | + | <figcaption style="width:60%;"><b>Figure 4: Purified Delftibactin precipitates gold from gold solution.</b> From left to right: ddH<sub>2</sub>O, 1:10 ACM media in water, 1:10 supernatant of <i>D. acidovorans</i> SPH-1 in water, 1:10 filtered supernatant of <i>D. acidovorans</i> SPH-1 in water, 1:10 purified delftibactin in water; gold solution: 0.6 µg/ml HAuCl<sub>4</sub>.</figcaption> |

</a> | </a> | ||

</center> | </center> | ||

| - | <br> | + | <br/> |

| + | <br/> | ||

<center> | <center> | ||

| - | <a class="fancybox fancyGraphical" href="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/1/ | + | <a class="fancybox fancyGraphical" href="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/1/11/Heidelberg_Microtof-Delftia.png" title="<i>D. acidovorans</i> SPH-1 secretes delftibactin. Micro-TOF results for ACM media (top) compared to purified supernatant of a <i>D. acidovorans</i> SPH-1 liquid culture (middle). Delftibactin is present in <i>D. acidovorans</i> SPH-1 supernatant but not in the pure ACM-media as can be seen as peak of the Micro-TOF spectra at about 1055.5, 1033.5, 517.2 and 539.2 shown in the enlargements (bottom)."> |

| - | <img style="width: | + | <img style="width:60%; margin-bottom:10px; padding:1%;border-style:solid;border-width:1px;border-radius: 5px;" src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/1/11/Heidelberg_Microtof-Delftia.png"> |

| - | <figcaption style="width:60%;"><b> | + | <figcaption style="width:60%;"><b>Figure 5: <i>D. acidovorans</i> SPH-1 secretes delftibactin.</b> Micro-TOF results for ACM media (top) compared to purified supernatant of a <i>D. acidovorans</i> SPH-1 liquid culture (middle). Delftibactin is present in <i>D. acidovorans</i> SPH-1 supernatant but not in the pure ACM-media as can be seen as peak of the Micro-TOF spectra at about 1055.5, 1033.5, 517.2 and 539.2 shown in the enlargements (bottom).</figcaption> |

</a> | </a> | ||

</center> | </center> | ||

| Line 225: | Line 239: | ||

| - | <p style=" | + | <p style="clear:both">Moreover we were interested in the potential of delftibactin for the recycling of gold from electronic waste. An important prerequisite for efficient gold recycling from electronic waste is the feasibility for gold precipitation from gold solutions of low concentration. Undoubtedly, this is likely the case for most gold solutions derived from electronic waste.Therefore, we used an old, broken CPU and established a protocol for dissolving gold from gold-containing metal waste. We incubated gold covered CPU pins in <i>aqua regia</i> resulting in a gold-ion containing solution |

| + | (<a class="fancybox fancyFigure" title="<i>D. acidovorans</i> can be used for gold recovery from electronic waste. a) Pins removed from an old CPU. b) Green solution of dissolved pins in aqua regia. c) Gold chloride solution obtained after the dilution of an old CPU. d) "Dissolved electronic waste" and D. acidovorans. e) "Dissolved electronic waste" on D. acidovorans. f) Precipitated "dissolved electronic waste" and D. acidovorans." href="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/b/b1/Zusammenstellung2.png" rel="gallery1">Fig. 6a-c</a>). | ||

| + | We showed precipitation of dissolved gold recovered from electronic waste by <i>D. acidovorans</i>. Adding this solution to <i>D. acidovorans</i> SPH-1 agar plates resulted in the formation of solid gold nanoparticles | ||

| + | (<a class="fancybox fancyFigure" title="<i>D. acidovorans</i> can be used for gold recovery from electronic waste. a) Pins removed from an old CPU. b) Green solution of dissolved pins in aqua regia. c) Gold chloride solution obtained after the dilution of an old CPU. d) "Dissolved electronic waste" and D. acidovorans. e) "Dissolved electronic waste" on D. acidovorans. f) Precipitated "dissolved electronic waste" and D. acidovorans." href="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/b/b1/Zusammenstellung2.png" rel="gallery1">Fig. 6d-f</a>). </p> | ||

| - | |||

<br/> | <br/> | ||

<center> | <center> | ||

| - | <a class="fancybox fancyGraphical" href="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/b/b1/Zusammenstellung2.png" title="Pins removed from an old CPU."> | + | <a class="fancybox fancyGraphical" href="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/b/b1/Zusammenstellung2.png" title="<i>D. acidovorans</i> can be used for gold recovery from electronic waste. a) Pins removed from an old CPU. b) Green solution of dissolved pins in aqua regia. c) Gold chloride solution obtained after the dilution of an old CPU. d) "Dissolved electronic waste" and D. acidovorans. e) "Dissolved electronic waste" on D. acidovorans. f) Precipitated "dissolved electronic waste" and D. acidovorans."> |

| - | <img style="width:70%; margin-bottom:10px; padding:1%;border-style:solid;border-width:1px;border-radius: 5px;" src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/b/b1/Zusammenstellung2.png" | + | <img style="width:70%; margin-bottom:10px; padding:1%;border-style:solid;border-width:1px;border-radius: 5px;" src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/b/b1/Zusammenstellung2.png"> |

| - | <figcaption style="width: | + | <figcaption style="width:70%;"><b>Figure 6: <i>D. acidovorans</i> can be used for gold recovery from electronic waste.</b> a) Pins removed from an old CPU. b) Green solution of dissolved pins in aqua regia. c) Gold chloride solution obtained after the dilution of an old CPU. d) "Dissolved electronic waste" and <i>D. acidovorans</i>. e) "Dissolved electronic waste" on <i>D. acidovorans</i>. f) Precipitated "dissolved electronic waste" and <i>D. acidovorans</i>.</figcaption> |

</a> | </a> | ||

</center> | </center> | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

| + | <p style="clear:both">Taken together, we have successfully established a method enabling the recycling of pure gold from electronic waste using delftibactin produced by <i>D. acidovorans</i>. </p> | ||

| - | <p | + | <p>Although the recycling was working efficiently in our hands, the approach of using the natural <i>D. acidovorans</i> bacterial strain for delftibactin production on a larger scale has the following disadvantages: |

| - | <li> <i>D. acidovorans</i> are relatively slow in growth (colony formation on plates occurs after 2-3 days)</li> | + | <ol> |

| - | <li> Efficient production of delftibactin requires the strain to be grown in ACM media, which is | + | <li> <i>D. acidovorans</i> are relatively slow in growth (colony formation on plates occurs after 2-3 days) </li> |

| + | <li> Efficient production of delftibactin requires the strain to be grown in ACM media, which is moreexpensive, compared to typical <i>E. coli</i> growth media, making the procedure less economic.</li></ol></p> | ||

| - | <p style="clear:both;">Therefore, we wanted to engineer an <i>E. coli</i> strain producing delftibactin in high yields, thereby circumventing the | + | <p style="clear:both;">Therefore, we wanted to engineer an <i>E. coli</i> strain producing delftibactin in high yields, thereby circumventing the above mentioned limitations.</p> |

| - | <h3> | + | <h3>Expression of Del Cluster Genes in <i>E. coli</i></h3> |

| - | <p> | + | <p>We developed a cloning strategy which allowed us to clone all necessary genes encoding the delftibactin-producing non-ribosomal peptide synthetases and polyketide synthetases from the del cluster (about 59 kbp in total) and express them in <i>E. coli</i>. In addition, introducing the methylmalonyl-CoA pathway into <i>E. coli</i> provided one of the basic substrates for the del pathway which is endogenously not present in <i>E. coli</i>.</p> |

| + | |||

| + | <p>Therefore, our initial aim was the genomic integration of the genes encoding for the methylmalonyl-CoA pathway into <i>E. coli</i> using the lambda red system established by [13]. This pathway is required for sufficient delftibactin production, as it supplies the substrate methylmalonyl-CoA for DelF, the PKS of the delftibactin cluster. As several genomc integration attempts did not yield positive results, as verified by colony-PCR with the forward primer binding to the genomic region and the reverse primer to the insert (a representative gel image can be seen in the <a href="/Team:Heidelberg/Delftibactin/MMCoA#2013-07-02">lab journal</a>), a new strategy was developed. Two plasmids were created: pIK2 containing the mm-CoA pathway amplified from <i>Streptomyces coelicolor</i> as well as the PPTase sfp, amplified from <i>Bacillus subtilis</i> in the BioBrick backbone pSB3C5. The permeability device (<a href='http://parts.igem.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_I746200'>BBa_I746200</a>) for the outer membrane of <i>E. coli</i> was cloned into another plasmid (pIK1). Since the iGEM Team Cambridge 2007 showed that <a href='http://parts.igem.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_I746200'>BBa_I746200</a> is toxic if produced in higher quantities we inserted it into pIK2 between the two terminators driven by a weak promoter (<a href='http://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_J23114'>BBa_J23114</a>) and a weak RBS (<a href='http://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_B0030'>BBa_B0030</a>), resulting in the final plasmids pIK8 with a total size of 9,467 bp, which was transformed into the <i>E.coli</i> strains DH10ß and BL21 DE3 via electroporation.</p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | <p>Details of our cloning strategy are shown in | ||

| + | <a class="fancybox fancyFigure" title="Cloning strategy for the production of delftibactin in <i>E. coli</i>. The genes DelA to DelH, DelL, DelO and DelP from the cluster for delftibactin production are introduced in two plasmids (shown in yellow). Additional genes needed for the production and export of delftibactin are located on a third plasmid (shown in blue)." href="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/0/03/Heidelberg_Delftibactin_Intro.png" rel="gallery1">Fig. 7</a>. | ||

| + | Notably, the three plasmids we wanted to assemble are of large size (23, 32 and 10 kbp in size) and cloning was further complicated due to the high GC content and presence of repetitive elements within the del genes.</p> | ||

<br/> | <br/> | ||

<center> | <center> | ||

| - | <a class="fancybox fancyGraphical" href="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/0/03/Heidelberg_Delftibactin_Intro.png" title=" | + | <a class="fancybox fancyGraphical" href="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/0/03/Heidelberg_Delftibactin_Intro.png" title="Cloning strategy for the production of delftibactin in <i>E. coli</i>. The genes DelA to DelH, DelL, DelO and DelP from the cluster for delftibactin production are introduced in two plasmids (shown in yellow). Additional genes needed for the production and export of delftibactin are located on a third plasmid (shown in blue)."> |

| - | <img style="width:50%; margin-bottom:10px; padding:1%;border-style:solid;border-width:1px;border-radius: 5px;" src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/0/03/Heidelberg_Delftibactin_Intro.png" | + | <img style="width:50%; margin-bottom:10px; padding:1%;border-style:solid;border-width:1px;border-radius: 5px;" src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/0/03/Heidelberg_Delftibactin_Intro.png"> |

| - | <figcaption style="width:60%;"><b> | + | <figcaption style="width:60%;"><b>Figure 7: Cloning strategy for the production of delftibactin in <i>E. coli</i>.</b> The genes DelA to DelH, DelL, DelO and DelP from the cluster for delftibactin production are introduced in two plasmids (shown in yellow). Additional genes needed for the production and export of delftibactin are located on a third plasmid (shown in blue).</figcaption> |

</a> | </a> | ||

</center> | </center> | ||

| - | <br | + | <br/> |

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

<h3>Gibson Assembly & Transformation</h3> | <h3>Gibson Assembly & Transformation</h3> | ||

| - | <p>Assembly of plasmids above | + | <p>Assembly of plasmids above 30 kbp in size composing of multiple fragments is challenging when using conventional restriction enzyme based cloning. Thus, we decided to use <a href='https://2010.igem.org/Team:Cambridge/Gibson/Protocol'>Gibson Assembly</a>, a method which was introduced to the iGEM community by Cambridge in iGEM 2010 as a powerful alternative to common cloning procedures. The assembled constructs of up to 32 kbp in size were transformed into <i>E. coli</i> via electroporation. Correct assembly of the fragments was tested by analytical restriction digests. The exemplary restriction digests shown above |

| + | (<a class="fancybox fancyFigure" title="Restriction digest of plasmids coding for MMCoA, DelH and DelRest which are needed in the NRPS/PKS pathway to generated Delftibactin. a) Digested minipreps of the pIK8-plasmid of four different clones. Clones 6 and 9 show the expected pattern. b) shows the minipreps of one clone of <i>E. coli</i> transformed with the 32 kbp DelRest plasmid which was digested with three different enzymes. All digests show the expected patterns. c) shows the restriction digest of the DelH plasmid with PvuI. The digest of clone 5 shows the anticipated bands and is probably positive." href="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/f/fa/Heidelberg_DelCluster_Digest.png" rel="gallery1">Fig. 8</a>) confirmed the correct assembly of the three desired constructs as it displays the expected band pattern. For cloning of the mm-CoA pathway, clones (6 and 9) show the expected restriction pattern | ||

| + | (<a class="fancybox fancyFigure" title="Restriction digest of plasmids coding for MMCoA, DelH and DelRest which are needed in the NRPS/PKS pathway to generated Delftibactin. a) Digested minipreps of the pIK8-plasmid of four different clones. Clones 6 and 9 show the expected pattern. b) shows the minipreps of one clone of <i>E. coli</i> transformed with the 32 kbp DelRest plasmid which was digested with three different enzymes. All digests show the expected patterns. c) shows the restriction digest of the DelH plasmid with PvuI. The digest of clone 5 shows the anticipated bands and is probably positive." href="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/f/fa/Heidelberg_DelCluster_Digest.png" rel="gallery1">Fig. 8a</a>). Sequencing of the assembly sites of these constructs confirmed the restriction digest results.</p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <p>Cloning of the DelRest plasmid was validated by different suitable analytic restriction digests | ||

| + | (<a class="fancybox fancyFigure" title="Restriction digest of plasmids coding for MMCoA, DelH and DelRest which are needed in the NRPS/PKS pathway to generated Delftibactin. a) Digested minipreps of the pIK8-plasmid of four different clones. Clones 6 and 9 show the expected pattern. b) shows the minipreps of one clone of <i>E. coli</i> transformed with the 32 kbp DelRest plasmid which was digested with three different enzymes. All digests show the expected patterns. c) shows the restriction digest of the DelH plasmid with PvuI. The digest of clone 5 shows the anticipated bands and is probably positive." href="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/f/fa/Heidelberg_DelCluster_Digest.png" rel="gallery1">Fig. 8b</a>) | ||

| + | and also confirmed by sequencing. The sequence was compared with the available <i>D. acidovorans</i> SPH-1 reference sequence obtained from NCBI (for further information please visit our <a href='https://2013.igem.org/Team:Heidelberg/Delftibactin'>labjournal</a>). The high quality of the alignment shows that Gibson assembly is a suitable cloning approach for rapid assembly of large NRPS and PKS expression constructs.</p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <p>Analytical restriction digest of DelH | ||

| + | (<a class="fancybox fancyFigure" title="Restriction digest of plasmids coding for MMCoA, DelH and DelRest which are needed in the NRPS/PKS pathway to generated Delftibactin. a) Digested minipreps of the pIK8-plasmid of four different clones. Clones 6 and 9 show the expected pattern. b) shows the minipreps of one clone of <i>E. coli</i> transformed with the 32 kbp DelRest plasmid which was digested with three different enzymes. All digests show the expected patterns. c) shows the restriction digest of the DelH plasmid with PvuI. The digest of clone 5 shows the anticipated bands and is probably positive." href="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/f/fa/Heidelberg_DelCluster_Digest.png" rel="gallery1">Fig. 8c</a>) | ||

| + | also gave rise to a number of positive clones. However, the sequencing results derived from all DelH showed various mutations, which were exclusively located within the region of the first DelH forward primer. Most of these mutations are deletions present in the first 30 bp of the DelH coding region thereby resulting in frameshifts and formation of a stop codon disposing <i>E. Coli</i> of expression of DelH. As there was no clone without mutations, we proceeded with DelH clone C5, as this clone did not have any bp deletion but only harbored a substitution mutation at bp position 28 of the ORF, leading to the conversion of Alanine at position 10 to Threonine. Two representative sequences compared to <i>D. acidovorans</i> SPH-1 are listed below (Tab. 1) and display two of the observed mutations in different DelH clones. </p> | ||

<br/> | <br/> | ||

<center> | <center> | ||

| - | <a class="fancybox fancyGraphical" href="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/f/fa/Heidelberg_DelCluster_Digest.png" title="Restriction digest of | + | <a class="fancybox fancyGraphical" href="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/f/fa/Heidelberg_DelCluster_Digest.png" title="Restriction digest of plasmids coding for MMCoA, DelH and DelRest which are needed in the NRPS/PKS pathway to generated Delftibactin. a) Digested minipreps of the pIK8-plasmid of four different clones. Clones 6 and 9 show the expected pattern. b) shows the minipreps of one clone of <i>E. coli</i> transformed with the 32 kbp DelRest plasmid which was digested with three different enzymes. All digests show the expected patterns. c) shows the restriction digest of the DelH plasmid with PvuI. The digest of clone 5 shows the anticipated bands and is probably positive."> |

| - | <img style="width:60%; margin-bottom:10px; padding:1%;border-style:solid;border-width:1px;border-radius: 5px;" src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/f/fa/Heidelberg_DelCluster_Digest.png" | + | <img style="width:60%; margin-bottom:10px; padding:1%;border-style:solid;border-width:1px;border-radius: 5px;" src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/f/fa/Heidelberg_DelCluster_Digest.png"> |

| - | <figcaption style="width:60%;"><b> | + | <figcaption style="width:60%;"><b>Figure 8: Restriction digest of plasmids coding for MMCoA, DelH and DelRest which are needed in the NRPS/PKS pathway to generated Delftibactin.</b> a) Digested minipreps of the pIK8-plasmid of four different clones. Clones 6 and 9 show the expected pattern. b) shows the minipreps of one clone of <i>E. coli</i> transformed with the 32 kbp DelRest plasmid which was digested with three different enzymes. All digests show the expected patterns. c) shows the restriction digest of the DelH plasmid with PvuI. The digest of clone 5 shows the anticipated bands and is probably positive.</figcaption> |

</a> | </a> | ||

</center> | </center> | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | </html>''Tab.1 DelH 5’ sequence, in which most mutations were observed. The ATG start codon is depicted in bold. The table shows the sequence comparison between the DelH reference strand of | + | </html>''Tab.1 DelH 5’ sequence, in which most mutations were observed. The ATG start codon is depicted in bold. The table shows the sequence comparison between the DelH reference strand of <i>D. acidovorans</i> and two different exemplary <i>E. coli</i> clones transformed with the plasmid pHM04 (assembled DelH expression vector). The second line shows the accumulated deletion and the third line shows the clone containing 'only' single base pair substitution. Deletions appeared quite frequently while a substitution was only found in a single clone C5. The substitution changes the corresponding Alanine codon to Threonine.'' |

<center> | <center> | ||

{| class="wikitable" | {| class="wikitable" | ||

| Line 283: | Line 314: | ||

! Organism !! Plasmid containing !! DNA -Sequence !!Conclusion | ! Organism !! Plasmid containing !! DNA -Sequence !!Conclusion | ||

|- | |- | ||

| - | | | + | | <i>D. acidovorans</i>|| none || ATG GACCGTGGC CGCCTGCGC CAAATCGC || correct |

|- | |- | ||

| - | | | + | | <i>E. coli</i> DH10ß|| pHM04 || ATG GACCGTG-C CGCCTGCGC CAAATCGC || deletion |

|- | |- | ||

| - | | | + | | <i>E. coli</i> DH10ß C5 || pHM04 || ATG GACCGTGGC CGCCTGCGC CAAATCAC || substitution |

|} | |} | ||

</center> | </center> | ||

<html> | <html> | ||

| - | <p>Due to | + | <p>Due to these observations, we hypothesize that expression of DelH is toxic for <i>E. coli</i>. Therefore natural selection only leads to survival of those clones which incorporate constructs giving rise to unfunctional, truncated DelH proteins or avoiding any expression. This phenomenon of frequent mutations within the primer binding site was also observed when we started cloning of the permeability device used in the pIK8 construct. The sequenced plasmids displayed a high accumulation of mutations compared to other constructs. In case of the methylmalonyl-CoA plasmid (pIK8), the problem was solved by the usage of a weak promoter and a weak ribosome binding site from the parts registry for driving the expression of the permeability device (see above). Based on this knowledge, DelH is currently being assembled into the desired backbone <a href='http://parts.igem.org/Part:pSB6A1'>pSB6A1</a> containing a weak promoter <a href='http://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_J23114'>BBa_J23114</a> and the ribosome binding site <a href='http://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_B0032'>BBa_B0032</a>, also reducing expression. While the new plasmid is constructed, the following experiments were performed with the C5 clone as we hypothesized that DelH C5 bearing the single nucleotide exchange at position 28 might still show expression of functional DelH when transformed into <i>E. coli</i> (the corresponding amino acid exchange is located at the N-terminus).</p> |

| - | + | ||

<h3>Expression of the Delftibactin NRPSs & Associated Genes</h3> | <h3>Expression of the Delftibactin NRPSs & Associated Genes</h3> | ||

| - | <p> | + | <p>For further characterization of our constructs, we analyzed expression of the delftibactin NRPS/PKS pathway in <i>E. coli</i>. For expression of DelH and DelRest, SDS-PAGEs were conducted followed by Coomassie staining. Native cells as well as cells transformed with the plasmid backbones obtained from the parts registry containing the used antibiotic resistance markers served as control groups. The proteins DelE, DelG and DelH are significantly larger than any protein that is expressed by our host <i>E. coli</i>. Therefore, the expression of the introduced genes was detectable on the SDS-PAGE |

| + | (<a class="fancybox fancyFigure" title="<i>E. coli</i> express the NRPS of the delftibactin production pathway. SDS-PAGE of: a) <i>E. coli</i> DH10ß colony D8w containing the DelRest plasmid pFSN. <i>E. coli</i> DH10ß transformed with pSB4K5 is used as negative control. The bands at the heights of about 190 kDa and 350 kDa (depicted by black arrows) indicate the expression of DelE and DelG. b) <i>E. coli</i> BL21 DE3 colony C5 containing the DelH plasmid. <i>E. coli</i> BL21 is used as negative control. A weak band at a height of more than 260 kDa (largest protein band of the ladder) is present. This could potentially be a band at the height of 670 kDa and thus hint at the production of the NRPS DelH." href="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/1/18/Heidelberg_SDS-PAGES.png" rel="gallery1">Fig. 9</a>) | ||

| + | without specific labeling of the proteins. Although expression of these large proteins was weak, clear distinct bands of the sizes predicted for DelE and DelG were detected. Accordingly a band at the predicted size of DelH for the clone transformed with DelH C5 was visible. As the lac promoter regulating expression of DelE and DelG also drives expression of DelA, DelB, DelC, DelD and DelF, one can conclude simultaneous expression of these del proteins. This is also in accordance with the predicted distribution of promoters within the delfticbatin cluster. </p> | ||

<br/> | <br/> | ||

<center> | <center> | ||

| - | <a class="fancybox fancyGraphical" href="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/1/18/Heidelberg_SDS-PAGES.png" title="SDS- | + | <a class="fancybox fancyGraphical" href="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/1/18/Heidelberg_SDS-PAGES.png" title="<i>E. coli</i> express the NRPS of the delftibactin production pathway. SDS-PAGE of: a) <i>E. coli</i> DH10ß colony D8w containing the DelRest plasmid pFSN. <i>E. coli</i> DH10ß transformed with pSB4K5 is used as negative control. The bands at the heights of about 190 kDa and 350 kDa (depicted by black arrows) indicate the expression of DelE and DelG. b) <i>E. coli</i> BL21 DE3 colony C5 containing the DelH plasmid. <i>E. coli</i> BL21 is used as negative control. A weak band at a height of more than 260 kDa (largest protein band of the ladder) is present. This could potentially be a band at the height of 670 kDa and thus hint at the production of the NRPS DelH."> |

| - | <img style="width:60%; margin-bottom:10px; padding:1%;border-style:solid;border-width:1px;border-radius: 5px;" src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/1/18/Heidelberg_SDS-PAGES.png" | + | <img style="width:60%; margin-bottom:10px; padding:1%;border-style:solid;border-width:1px;border-radius: 5px;" src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/1/18/Heidelberg_SDS-PAGES.png"> |

| - | <figcaption style="width:60%;"><b> | + | <figcaption style="width:60%;"><b>Figure 9: <i>E. coli</i> express the NRPS of the delftibactin production pathway.</b>SDS-PAGE of: a) <i>E. coli</i> DH10ß colony D8w containing the DelRest plasmid pFSN. <i>E. coli</i> DH10ß transformed with pSB4K5 is used as negative control. The bands at the heights of about 190 kDa and 350 kDa (depicted by black arrows) indicate the expression of DelE and DelG. b) <i>E. coli</i> BL21 DE3 colony C5 containing the DelH plasmid. <i>E. coli</i> BL21 is used as negative control. A weak band at a height of more than 260 kDa (largest protein band of the ladder) is present. This could potentially be a band at the height of 670 kDa and thus hint at the production of the NRPS DelH.</figcaption> |

</a> | </a> | ||

</center> | </center> | ||

<br/> | <br/> | ||

| - | <p> | + | |

| + | |||

| + | <p>Furthermore, the expression of the PPTase was verified by performing an IndC activity assay established by the <a href='https://2013.igem.org/Team:Heidelberg/Project/Tag-Optimization'>indigoidine subproject</a>. The indigoidine synthetase IndC activity is dependent on the presence of a functional PPTase. Upon activation, indC produces the blue pigment indigoidine. Co-transformation of the corresponding plasmid pIK8 construct (enabling PPTase expression) with an IndC indigoidine synthetase expression construct lacking a PPTase expression cassette (<a href='https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/7/7a/Heidelberg_PRB22.png'>pRB22</a>) was conducted. The transformed <i>E. coli</i> displayed inhibited growth and developed the expected blue phenotype. From these results, we conclude that the PPTase on pIK8 is functionally expressed (note: decelerated growth kinetics of <i>E. coli</i> results from the metabolic burden that is caused by the synthesis of the indigoidine).</p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <p>For proving the production of the permeability device which is needed for export of delftibactin, a zone of inhibition test with bactracin was performed. Bacitracin is an antibiotic not able to pass the bacterial cell wall by passive transport [14]. Growth of bacteria containing the permeability device was inhibited upon application of bacitracin confirms the expression of the transporter. Growth of control cells without the device was not impaired by application of bacitracin | ||

| + | (<a class="fancybox fancyFigure" title="Zone of inhibition test proves functionality of the permeability device. Left: TOP10-pIK8.6, right: TOP10-pIK8.1 (negative control); counterclockwise, starting top right: 8 µl, 4 µl, 2 µl, 1 µl bacitracin. It can be seen that the device works as the cells transformed with the construct die upon application of bacitracin." href="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/4/40/Heidelberg_Bacitracin.png" rel="gallery1">Fig. 10</a>).</p> | ||

<br/> | <br/> | ||

<center> | <center> | ||

| - | <a class="fancybox fancyGraphical" href="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/4/40/Heidelberg_Bacitracin.png" title="Left: TOP10-pIK8.6, right: TOP10-pIK8.1 (negative control); counterclockwise, starting top right: 8 µl, 4 µl, 2 µl, 1 µl bacitracin."> | + | <a class="fancybox fancyGraphical" href="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/4/40/Heidelberg_Bacitracin.png" title="Zone of inhibition test proves functionality of the permeability device. Left: TOP10-pIK8.6, right: TOP10-pIK8.1 (negative control); counterclockwise, starting top right: 8 µl, 4 µl, 2 µl, 1 µl bacitracin. It can be seen that the device works as the cells transformed with the construct die upon application of bacitracin."> |

| - | <img style="width:60%; margin-bottom:10px; padding:1%;border-style:solid;border-width:1px;border-radius: 5px;" src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/4/40/Heidelberg_Bacitracin.png" | + | <img style="width:60%; margin-bottom:10px; padding:1%;border-style:solid;border-width:1px;border-radius: 5px;" src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/4/40/Heidelberg_Bacitracin.png"> |

| - | <figcaption style="width:60%;"><b> | + | <figcaption style="width:60%;"><b>Figure 10: Zone of inhibition test proves functionality of the permeability device.</b> Left: TOP10-pIK8.6, right: TOP10-pIK8.1 (negative control); counterclockwise, starting top right: 8 µl, 4 µl, 2 µl, 1 µl bacitracin. It can be seen that the device works as the cells transformed with the construct die upon application of bacitracin.</figcaption> |

</a> | </a> | ||

</center> | </center> | ||

<br/> | <br/> | ||

| - | <p> | + | <p style="clear:both">In conclusion, we successfully expressed the recombinant delftibactin NRPS/ PKS pathway as well as the required methylmalonyl-CoA pathway, the PPTase and permeability device in <i>E. coli</i>. </p> |

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | <p> | + | <p>Furthermore, we showed, that it is not only possible to assemble large plasmids (in sum these were 67 kpb in total size in our case) and transform them into <i>E. coli</i>, but demonstrated successful expression of large NRPS/PKS modules in our host strain.</p> |

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

<h2>Discussion and outlook</h2> | <h2>Discussion and outlook</h2> | ||

| - | + | <h3>Potential of the NRP Delftibactin for the Recovery of Gold from Electronic Waste</h3> | |

| + | <p>Delftibactin is a secondary metabolite naturally produced by <i>D. acidovorans</i> and has the ability to specifically precipitate gold from solutions [7]. Today, electronic waste has become an immense environmental problem not only in developed nations, but also third-world countries through the increasing export of waste and disposal challenges.</p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <p>Therefore, an efficient method to recycle electronic waste is urgently needed. From our work we concluded, that delftibactin could be used as an efficient substance to recycle gold. In fact, many different electronic scraps contain considerable gold amounts such as PC mainboards (566 ppm in terms of weight) and mobile phones (350 ppm)[15]. Those electronic devices are more and more demanded by society though their average lifetime seems to decrease steadily. To date, existing methods for gold recycling and safe disposal of electronic waste are still very energy-consuming and harmful to the environment[16].</p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <p>Nowadays, harsh substances, such as strong acids, are conventionally used for leaching gold from electronic waste [17]. Applied chemicals pose a potential thread to the environment as they could contaminate the biosphere. Biological agents could become an alternative to chemical clearance of metals from electronic waste. Nature's gold-altering microbes are non-pollutive and they are not genetically modified. While bacteria such as <i>Cupriavidus metallidurans</i> convert the dissolved element to its metallic form inside the cell [18], species like <i>Chromobacterium violaceum</i> [6] or <i>D. acidovorans</i> [7] secrete substances to the surrounding medium for gold precipitation. These microorganisms can therefore be engineered to increase the yield of bioleaching substances. </p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <h3>Successful Recycling of Gold from Electronic Waste with Delftibactin and Transformation of Delftibactin Gene Cluster in <i>E. coli</i></h3> | ||

| + | <p>In our experiments, we successfully managed to dissolve electronic waste in aqua regia (i.e. nitro-hydrochloric acid) and neutralize the solution to receive gold chloride. When we added the supernatant of a <i>D. acidovorans</i> liquid culture to the gold chloride solution, pure gold nanoparticles were precipitated. Furthermore, we were able to melt the precipitated gold resulting in little gold flakes. The procedure already worked on a small scale in our project. With increased efforts, yields of delftibactin for industrial applications are conceivable. In those dimensions, gold could easily be recycled. To investigate the question if the recovery of gold is feasible with delftibactin <a href="https://2013.igem.org/Team:Heidelberg/Modelling/Gold_Recovery">modeling</a> of the potential procedure was carried out. With delftibactin there is no further need for chemical reducing reagents to purify gold from solution. Nevertheless, the efficiency of our approach still has to be improved. We were able to apply delftibactin for the extraction of gold from electronic waste but still had to expose the CPUs with aqua regis to bring gold in solution. Ideally, one should get rid of the use of this highly corrosive mixture. </p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <p>To further increase the efficiency of delftibactin production, we aimed at transferring the entire synthesis machinery for delftibactin into <i>E. coli</i>. As the NRPS producing delftibactin is a very large enzyme complex consisting of many modules, amplification, cloning and transformation of the constructs was very challenging. Nonetheless, we successfully managed to amplify, assemble and transform all of the genes (in sum 59 kbp) required for production of delftibactin. In this process, we established protocols, including Gibson assembly of large fragments, and transformation of those constructs into <i>E. coli</i> via electroporation. Optimized procedures will ease the cloning of large customized NRPSs in future. </p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <h3>Successful Expression of NRPSs Despite Challenges Concerning the Toxicity of DelH</h3> | ||

| + | <p>A hurdle to overcome is that the DelH displayed an above-average mutation rate when present in <i>E. coli</i> without the rest of the delftibactin pathway genes. DelH could potentially be toxic to the <i>E. coli</i>. Therefore, cells select for mutations that render the clones unable to express a functional DelH protein [19]. In our experiments, the putative selection pressure towards non-functional DelH was manifested in deletions, insertions or substitutions in the respective ribsosome binding side or at the beginning of DelH. However, we managed to obtain a single clone, which only possessed a point mutation that potentially does not interfere with protein expression since no false stop codon was created and no frame shift was caused. Furthermore when introducing DelH without promotor or ribosome binding site we could obtain clones which did not have the mutations at the beginning of DelH. This is a clear indication that DelH in fact is toxic to <i>E. coli</i> when being expressed. The next step would be to clone the correct DelH into a backbone with weak promoter and ribosome binding site by conventional restriction enzyme based cloning, which would keep the detrimental impact of DelH as low as possible. However due to time limitations we have not been able to take this step yet. Nevertheless this strategy is very promising in obtaining a correct construct.</p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <p>Moreover we proved the expression of the proteins DelE and DelG. Even for the clone with promotor and only one point mutation we were able to show that DelH is successfully expressed in <i>E. coli</i>. The point mutation causes an amino acid exchange (Alanine to Threonine) at the N terminus of the protein. Our prediction of the tertiary structure of the N-terminus of DelH | ||

| + | (<a class="fancybox fancyFigure" title="Predicted tertiary structure formed by the first half of DelH using Phyre2. The N-terminus, which contains the mutation is located at the outer side of the protein (shown in blue)." href="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/5/53/DelH_Nterm.png" rel="gallery1">Fig. 11</a>) | ||

| + | indicated that the substituted amino acid in the mutant DelH is located at the outer side of the protein. Nevertheless it could still have an important function. Therefore it is not possible to foresee whether the mutation will have any effect on the function of DelH. However alanine is an unpolar amino acid whereas threonine is polar. If the mutation was in a functional region, this could have significant effects rendering DelH nonfunctional and keeping <i>E. coli</i> alive.</p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <br/> | ||

| + | <center> | ||

| + | <a class="fancybox fancyGraphical" href="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/5/53/DelH_Nterm.png" title="Predicted tertiary structure formed by the first half of DelH using Phyre2. The N-terminus, which contains the mutation is located at the outer side of the protein (shown in blue)."> | ||

| + | <img style="width:60%; margin-bottom:10px; padding:1%;border-style:solid;border-width:1px;border-radius: 5px;" src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/5/53/DelH_Nterm.png"> | ||

| + | <figcaption style="width:60%;"><b>Figure 11: Predicted tertiary structure formed by the first half of DelH using Phyre2.</b> The N-terminus, which contains the mutation is located at the outer side of the protein (shown in blue).</figcaption> | ||

| + | </a> | ||

| + | </center> | ||

| + | <br/> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <p>Furthermore DelH might not be toxic anymore in the context of the complete assembly line, as toxicity most likely derives from conversion of secondary metabolites to harmful compounds. Therefore another strategy would be to directly cotransform the three plasmids, namely DelH, DelRest (encoding all del genes except for delH) and the pIK8 construct (bearing the MethylMalonyl-CoA pathway, the PPTase sfp as well as the permeability device). Furthermore different host strains could be used as expression levels could potentially be controlled better. In particular, <i>E.Coli</i> BL21 DE3 cells seem to be suitable for this approach as they overexpress the lac repressor. All in all there are still many promising approaches to obtain a functional DelH construct and therefore enable <i>E. coli</i> to express delftibactin. Consequently the application of recombinantly expressed delftibactin for the recycling of gold from electronic waste becomes conceivable | ||

| + | (<a class="fancybox fancyFigure" title="Industrial application of delftibactin for gold recovery from electronic waste. The electronic waste would be dissolved and the supernatant of a bacteria culture producing delftibactin would be added. This would allow the easy recovery of the precipitated pure gold." href="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/4/47/Heidelberg_goldrecycling.png" rel="gallery1">Fig. 12</a>).</p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <br/> | ||

| + | <center> | ||

| + | <a class="fancybox fancyGraphical" href="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/4/47/Heidelberg_goldrecycling.png" title="Proposed industrial application of delftibactin for gold recovery from electronic waste. First, the electronic waste is dissolved. Subsequently, the supernatant of a bacteria culture producing delftibactin is added. This procedure allows for the easy recovery of the precipitated pure gold."> | ||

| + | <img style="width:60%; margin-bottom:10px; padding:1%;border-style:solid;border-width:1px;border-radius: 5px;" src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2013/4/47/Heidelberg_goldrecycling.png"> | ||

| + | <figcaption style="width:60%;"><b>Figure 12: Proposed industrial application of delftibactin for gold recovery from electronic waste.</b> First, the electronic waste is dissolved. Subsequently, the supernatant of a bacteria culture producing delftibactin is added. This procedure allows for the easy recovery of the precipitated pure gold.</figcaption> | ||

| + | </a> | ||

| + | </center> | ||

| + | <br/> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

</div> | </div> | ||

<div class="col-sm-12 jumbotron"> | <div class="col-sm-12 jumbotron"> | ||

<div class="references"> | <div class="references"> | ||

| - | <p>1. Eisler R, Wiemeyer SN (2004) Cyanide hazards to plants and animals from gold mining and related water issues. Reviews of environmental contamination and toxicology: 21–54.</p> | + | <p>1. Perrine Chancerel (2010) Substance flow analysis of the recycling of small waste electrical and electronic equipment - An assessment of the recovery of gold and palladium. Technische Universität Berlin, Fakultät III - Prozesswissenschaften</p> |

| - | <p> | + | <p>2. Gesine Kauffmann (08.12.2011) Elektroschrott – die neue Schürfstelle für Gold. Die Welt. http://www.welt.de/wissenschaft/umwelt/article13755992/Elektroschrott-die-neue-Schuerfstelle-fuer-Gold.html</p> |

| - | <p> | + | <p>3. Eisler R, Wiemeyer SN (2004) Cyanide hazards to plants and animals from gold mining and related water issues. Reviews of environmental contamination and toxicology: 21–54.</p> |

| - | <p> | + | <p>4. Eisler R (2004) Arsenic hazards to humans, plants, and animals from gold mining. In:. Reviews of environmental contamination and toxicology. Springer. pp. 133–165.</p> |

| - | <p> | + | <p>5. Donato DB, Nichols O, Possingham H, Moore M, Ricci PF, et al. (2007) A critical review of the effects of gold cyanide-bearing tailings solutions on wildlife. Environment international 33: 974–984.</p> |

| - | <p> | + | <p>6. Tay SB, Natarajan G, bin Abdul Rahim MN, Tan HT, Chung MCM, et al. (2013) Enhancing gold recovery from electronic waste via lixiviant metabolic engineering in Chromobacterium violaceum. Scientific reports 3.</p> |

| - | <p> | + | <p>7. Johnston CW, Wyatt MA, Li X, Ibrahim A, Shuster J, et al. (2013) Gold biomineralization by a metallophore from a gold-associated microbe. Nature chemical biology 9: 241–243.</p> |

| - | <p> | + | <p>8. Strieker M, Tanovic A, Marahiel MA (2010) Nonribosomal peptide synthetases: structures and dynamics. Current opinion in structural biology 20: 234–240.</p> |

| - | <p> | + | <p>9. Caboche S, Leclère V, Pupin M, Kucherov G, Jacques P (2010) Diversity of monomers in nonribosomal peptides: towards the prediction of origin and biological activity. Journal of bacteriology 192: 5143–5150.</p> |

| - | <p> | + | <p>10. Baltz RH (2011) Function of MbtH homologs in nonribosomal peptide biosynthesis and applications in secondary metabolite discovery. Journal of industrial microbiology & biotechnology 38: 1747–1760.</p> |

| - | <p> | + | <p>11. Quadri LE, Weinreb PH, Lei M, Nakano MM, Zuber P, et al. (1998) Characterization of Sfp, a <i>Bacillus subtilis</i> phosphopantetheinyl transferase for peptidyl carrier protein domains in peptide synthetases. Biochemistry 37: 1585–1595.</p> |

| - | <p> | + | <p>12. de Jong A, Pietersma H, Cordes M, Kuipers OP, Kok J (2012) PePPER: a webserver for prediction of prokaryote promoter elements and regulons. BMC genomics 13: 299.</p> |

| + | <p>13. Datsenko KA, Wanner BL. (2000) One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 6;97(12):6640-5.</p> | ||

| + | <p>14. Barbara A. Sampson, R. M. and S. A. B. (1989). Identification and Characterization of a New Gene of Escherichia coli K-12 Involved in Outer Membrane Permeability. Genetics, 122, 491-501.</p> | ||

| + | <p>15. Cui J, Zhang L. (2008) Metallurgical recovery of metals from electronic waste: a review. J Hazard Mater. 30;158(2-3):228-56. </p> | ||

| + | <p>16. Chancerel P, Bolland T, Rotter VS. (2011) Status of pre-processing of waste electrical and electronic equipment in Germany and its influence on the recovery of gold. Waste Manag Res. 2011 Mar;29(3):309-17.</p> | ||

| + | <p>17. C.Y. Yap, N. Mohamed (2007) An electrogenerative process for the recovery of gold from cyanide solutions. Chemosphere Volume 67, Issue 8, Pages 1502–1510</p> | ||

| + | <p>18. Reith F, Etschmann B, Grosse C, Moors H, Benotmane MA, et al. (2009) Mechanisms of gold biomineralization in the bacterium Cupriavidus metallidurans. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 106: 17757–17762.</p> | ||

| + | <p>19. Cárcamo J, Ravera MW, Brissette R, Dedova O, Beasley JR, et al. (1998) Unexpected frameshifts from gene to expressed protein in a phage-displayed peptide library. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 95: 11146–11151.</p> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

| Line 361: | Line 442: | ||

} | } | ||

}); | }); | ||

| + | |||

$(".fancybox.fancyFigure").fancybox({ | $(".fancybox.fancyFigure").fancybox({ | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

helpers : { | helpers : { | ||

title : { | title : { | ||

type: 'outside' | type: 'outside' | ||

}, | }, | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

} | } | ||

}); | }); | ||

Latest revision as of 03:53, 29 October 2013

Gold Recycling. Using Delftibactin to Recycle Gold from Electronic Waste.

Highlights

- Production and purification of delftibactin, a gold-precipitating NRP, from its native, cultured host Delftia acidovorans.

- Recovery of pure gold from electronic waste by Delftia acidovorans and purified delftibactin.

- Optimization of the Gibson assembly method for the creation of large plasmids (> 30 kbp) with high GC content.

- Amplification and cloning of all components required for recombinant delftibactin production.

- Transfer of the entire pathway from Delftia acidovorans for the synthesis of delftibactin to Escherichia coli.

Abstract

Undoubtedly, gold is one of the most precious materials on earth. Besides its common use in art and jewelry, gold is also an essential component of our modern computers and cell-phones. Due to the fast turn-over of today’s high-tech equipment, millions of tons of electronic waste accumulate each year containing tons of this valuable metal. The main approach nowadays to recycle gold from electronic waste is by electrolysis. Unfortunately, this is a highly inefficient and expensive procedure, preventing most of the gold from being recovered.

In this subproject we want to demonstrate that the gold-precipitating natural secondary metabolite delftibactin, a non-ribosomal peptide produced by the bacterium Delftia acidovorans, can be used for the efficient recovery of gold from electronic waste.

Moreover we want to show that very large constructs such as the genes needed for the production of delftibactin which are encoded on a 59 kbp long gene cluster can be succesfully inserted into Escherichia coli. Furthermore the aim is to recombinantly express the responsible NRPSs with the promising perspective that delftibactin could readily be produced and used as an efficient way of gold recycling from electronic waste.

We managed to introduce and express the genes needed for delftibactin production. Furthermore the recycling of gold from electronic waste with delftibactin was successful. Consequently the industrial usage of recombinantly expressed delftibactin as an efficient method to recover gold becomes conceivable.

Introduction

The quest for a magical substance to generate gold from inferior metals stirred the imagination of generations. However, this substance, the Philosopher’s Stone, stands for more than just the desire to produce gold. There was a time when the fabled Philosopher’s Stone also represented wisdom, rejuvenation and health. Nowadays, gold is still of great importance for us as it is needed for most of our electronic devices.

In 2007, more than two tons of gold, worth $92 million, were discarded hidden in electronic waste in Germany [1]. Most of the precious element ends up on waste disposal sites as only a minor fraction of 10-15% [2] of the gold is recycled also due to the small amounts per device. Since our planet’s gold supplies are limited, the metal is more and more depleted and the value of gold continuously reaches all-time highs. In order to satisfy our society’s need for gold, we have to develop heavy mining techniques involving strong acids, causing devastating impact on humans and environment [3] [4] [5].

Besides economical usage of the resource gold, one way to reduce global demands for gold is elevation of gold recovery [6]. Intriguingly, nature itself offers a structure that has been reported to efficiently extract pure gold from solutions containing gold ions. This fascinating molecule is called delftibactin and is in fact a small peptide secreted by a gold-ion-tolerant bacterium called Delftia acidovorans [7].

This extremophile has the incredible ability to withstand toxic amounts of gold ions in contaminated soil. If one could culture these bacteria and produce delftibactin in large scales, could one potentially recover gold from electronic waste in a cost- and energy-efficient way? But what is the special feature of delfibactin to precipitate gold that efficiently?

Delftibactin is a non-ribosomal peptide (NRP) [7] [8]. The efficient and non-pollutant large-scale production of this NRP in Escherichia coli could revolutionize the recovery of gold from electronic waste and additionally highlight the plethora of versatile applications for non-ribosomal peptide synthetases (NRPSs). The most striking feature of these non-ribosomal synthetases is their ability to incorporate far more than the 21 common amino acids into peptides. They make use of numerous modified and even non-proteinogenic amino acids to assemble peptides of diverse functions [9].

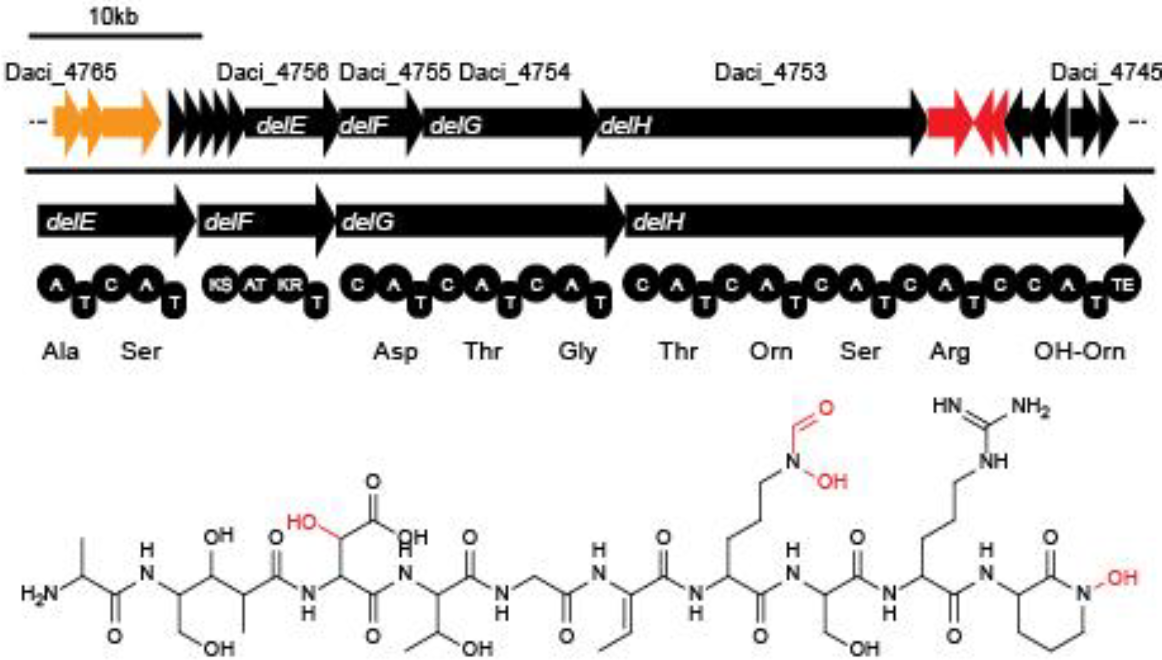

Delftibactin is a NRP produced by a hybrid NRPS/polyketide synthase (PKS) system. In their recent publication, Johnston and colleagues [7] predicted that the enzymes responsible for producing delftibactin are encoded on a single gene cluster, hereafter referred to as del cluster (Fig. 1). It comprises 59 kbp encoding for 21 genes. DelE, DelF, DelG and DelH constitute the hybrid NRPS/ PKS system producing delftibactin, with DelE, DelG and DelH comprising the NRPS and DelF the PKS. The remaining enzymes involved in the delftibactin synthesis pathway are required for maturation or post-synthesis modification of delftibactin. The predicted activities [7] of the proteins are:

- DelA: MbtH-like protein, most likely required for efficient delftibactin synthesis [10]

- DelB: thioesterase

- DelC: 4’-phosphopanteinyl transferase: required for maturation of ACP/PCP subunits

- DelD: taurine dioxygenase

- DelL: Ornithine N-monooxygenase

- DelP: N5-hydroxyornithine formyltransferase